5 Beyond the Quadrangle

The numerous symbolic references that have marked the history of universities are also captured in placemaking.

The arrangements and styles of buildings and spaces on a given territory are cultural glue. They attract and fix student and faculty loyalties. In fractured disciplinary environments, they create a sense of the whole being greater than any of its parts. They provide continuity: emotional and sentimental anchors in a world where experiences are fleeting. They unite the generations, keeping graduates close to the institution.

—Sheldon Rothblatt, A Note on the

Integrity

of the University

Academic rhythms change slowly—the school calendar and class meeting times; commencement and summer school; the progression of freshman, sophomore, junior, senior. The tempo of campus development has a different cadence, however. As new buildings and facilities are planned, constructed, and occupied, the calculus of possibilities is always changing. Likewise, when areas of green nature are marked, modified, preserved, or enhanced, new horizons of potentiality are revealed. Taken together, the man-made (human) and the natural (nonhuman) exist in a dynamic relationship.

As an intentional community of learning, by 1915 IU was settling into the campus it had occupied for a third of its ninety years as an institution. One sign of healthy growth was student enrollment, which in 1915 stood at 1,600—eight times as many as in 1885. Handsome limestone halls were arrayed around the original plot of Dunn’s Woods, and the campus footprint had grown to nearly 120 acres—six times larger than the original plot in 1885. The academic program was expanding with the creation of new professional schools and the offering of graduate work.

Concerned about reaching potential students who were not able to come to the Bloomington campus, President William Bryan established the Extension Division in 1914, which offered college courses as well as other educational services to citizens of the state. Aided by the advent of the automobile to augment the excellent intrastate rail services, Bloomington faculty traveled to many Indiana cities and towns to offer classes and programs. The extension programs filled a need, and by the mid-1920s, the number of statewide enrollments exceeded the student body in Bloomington.

The Bryan administration took steps to mobilize the growing number of living alumni. The Society of the Alumni had been formed in 1854 in response to the devastating campus fire that destroyed the main academic hall. Since that time, efforts to rouse this group to provide moral and financial support to the university had been successful but sporadic. Now there were some two thousand alumni, and their ranks swelled by several hundred each year at commencement. Keeping alumni informed about the university as well as their particular graduating class was a key part of the mobilization strategy. In 1914, a new publication was launched—the Indiana University Alumni Quarterly—designed to have broad appeal to former students as well as friends of the university. A special section titled Alumni Notes

in the magazine was dedicated to news of former students, arranged by graduation year.

In 1915, John W. Cravens, university registrar and secretary to the board of trustees, wrote a note in the new Alumni Quarterly after the recent purchase of additional land for the campus. He praised the work of botany professor David Mottier and the campus committee, who had been helping to enhance the campus landscape by planting native trees and shrubs for well over a decade. As a result,

Cravens declared, Indiana University has one of the most beautiful campuses in the country. Its hollows, hills, and level places, primeval forests and recently planted trees, make the campus very attractive. There is a charm about the campus that stays with one through his entire life. When a person has once been on the campus of Indiana University he is forever afterwards enthusiastic about its many entrancing features.

1 Perhaps not surprisingly, an alumnus and employee of Indiana University expressed these sentiments.

Another former student, novelist Theodore Dreiser, who attended during the 1889–90 school year, paid a visit to Bloomington in 1915 and marveled at the changes that had occurred since he last saw the campus twenty-five years before: After this came the university, wholly changed, but far more attractive than it had been in my day—a really beautiful school. I could find only a few things—Wylie Hall, the brook, a portion of some building which had formerly been our library. It had been so added to that it was scarcely recognizable.

2 Many new academic halls and supporting infrastructure served the growing student body, five times the size it was during Dreiser’s day, and the campus footprint had expanded nearly sixfold, to 117 acres.

5.1 A New Gymnasium

What had begun with the right-angle placement of Owen Hall and Wylie Hall in 1885 had developed into a large quadrangle, with the center green provided by trees rather than grass. Orderly rows of buildings framing the woods were complete on two sides and had been started on the other two—along Third Street and along Indiana Avenue. The main entrance to campus remained on Kirkwood Avenue, next to the 1908 University Library. With the recent availability of more campus land lying northeast of the quadrangle, including the Dunn family homestead, there was room to grow.

In 1915, the trustees decided that a new gymnasium would be the next building erected on campus, and they selected a site in the old apple orchard adjacent to the Dunn family house. To clear the site, the trustees permitted the students to cut down the trees and create piles of firewood for bonfires. About half of the student body, numbering eight hundred or so, showed up on October 21. The day started at the Student Building with a concert by the university band and a short talk by President Bryan, who then led the procession to the site. Both the president and Mrs. Bryan wielded axes to initiate the cutting. The men students joined in eagerly, chopping trees and piling wood, while women students made and served sandwiches. Enough wood was gathered for three bonfires at pep rallies for football season. IU anatomist and historian Burton Myers, who was there, later reported: This was a joyous occasion. The students felt that they were helping clear the way for this long-desired structure.

3 In the days following, the news reported that Bedford attorney Moses Dunn, who sold the family farm that became the core of IU’s campus, had died the day of the orchard’s destruction.4

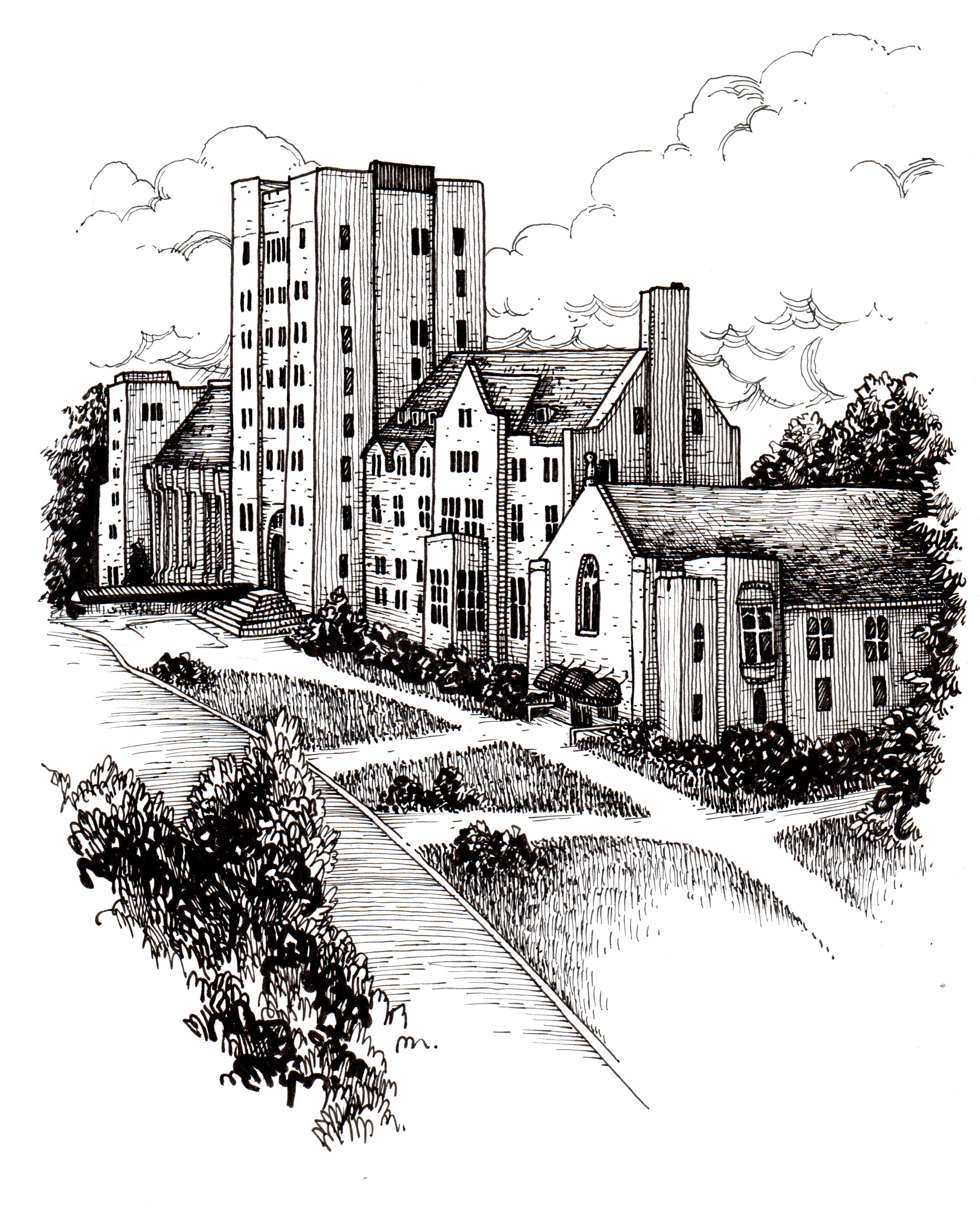

Representing the leading edge of campus expansion, the site was on Seventh Street, a couple of blocks away from the main part of campus on Kirkwood Avenue. As the first campus building on the north side of the stream known as Spanker’s Branch—informally referred to as Jordan River—the gymnasium’s imposing Gothic limestone architecture would be magnified by its site atop a terraced hill, commanding a view to the west.

With the prospect of new development on campus, President Bryan and the board of trustees thought it prudent to hire a consultant to prepare a master plan. Well-known for his work in the park system of Indianapolis, George Kessler, a landscape architect who worked around the Midwest, had a thriving business and was engaged in 1915.5 In November, Kessler shared his general ideas for campus planning with President Bryan and the board of trustees. He thought that planning should be comprehensive. Even though a grand design could only be realized in bits and pieces, and over a long period of years, still, we should always know where we are going.

6 By the following March, Kessler had reported back to the trustees with some suggestions, including ideas for buildings in the center of the quadrangle.

In May, President Bryan wrote to Kessler, conveying a diplomatic but firm message for the preservation of Dunn’s Woods:

Fully realizing your great ability as an artist, and my own position as a layman, I nevertheless get my courage together to say that I hope it may not be thought necessary to place any buildings in the front quadrangle between the Wylie, Kirkwood, Science line and Indiana Avenue. Whether the present forest can be replaced by another or not, this great space seems to me to have more distinction than any building which could be placed in it. This is the view, I happen to know, of Professor Brooks, Mr. Jenkins, the Trustees, and indeed of all of us. I am sure you would like to have us give you our view whatever it may be worth.7

Bryan, expressing a clear consensus among the IU academic community, took the remaining forest off the table for further development. There was no compelling reason to jettison the existing design of the thirty-year-old quadrangle.

As plans were developed for the new gymnasium, the entire board of trustees, along with architect Robert Frost Daggett, visited the site and the surrounding campus lands. This signaled the aspiration to coordinate the work of building architects with the efforts of landscape planners. The completed building, opened in 1917, was thronged with students at all hours. It served as a lonely architectural sentinel as future facilities were expected in the recent land purchases northwest of the quad. In the same period, replanting of the green space continued. A report indicated that 32,000 trees had been ordered as follows: 25,000 yellow poplar seedlings; 2,000 hard maple; 2,000 red oak; 3,000 pine, spruce, and fir.

8

The care expended on the physical plant was noticed by a distinguished visitor in 1918. Former US president Theodore Roosevelt visited Bloomington as the June commencement speaker. The ceremony was held in a natural ravine converted into an open-air amphitheater, behind Wylie and Kirkwood Halls. Equipped with a stage and bench seats, the amphitheater was a gift from the classes of 1909 through 1912.9 The former president began his remarks:

I want to say at the outset that I don’t think I have ever been at a more beautiful university commencement than this. I shall always keep in mind this scene here in the open by the university buildings, a university which…is approaching its centenary, here under these great trees, these maples and beeches, that have survived over from the primeval forest, to see all of you here and the graduating class composed mainly of girls this year—it is a sight I shall never forget,—it will always be with me.10

President Roosevelt expressed what students, staff, alumni, and other visitors already knew and appreciated about the campus.

In 1922, another distinguished visitor came to campus and stayed awhile. Theodore Clement Steele (T. C. Steele), a well-known painter from the art colony in neighboring Brown County, was appointed honorary professor of painting. He had a long association with the campus, painting portraits of many IU faculty, President Bryan among them, before turning to landscape interpretations. Bryan’s idea was that Steele’s very presence would help stimulate art appreciation on campus, thus contributing to the moral uplift of the student body. For his part, Steele rendered his mission to the students in a straightforward way: to see the Beautiful in nature and life.

11

The university provided studio space in the attic of the main library, above the large reading room. During his residency, Steele and his wife, Selma, spent the winters in Bloomington and the summers in Brown County, at their home near Belmont. The artist was modest and unpretentious about his work, and he welcomed visitors dropping in when the studio was open on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday each week. During clement weather, Steele set up his easel outdoors and painted en plein air. The resulting canvases showed different campus buildings, such as the Student Building and Kirkwood Observatory, and landscape features, such as the central woods and the Jordan River. In 1923, the Union Board bought six of Steele’s paintings, which provided the nucleus for the art collection of the Indiana Memorial Union. Although his original term as honorary professor was meant to last only a year, he stayed on happily until 1926, the year of his death.12

5.2 Campuses, the Old and the New

To mark the centennial of the first buildings on the old campus, in 1922, administrative factotum John Cravens penned a series of three articles for the Alumni Quarterly. By that time, the university had been occupying the campus at Dunn’s Wood for a third of a century. A former school superintendent and court clerk for Monroe County, Cravens occupied a unique position in the university. Appointed as IU registrar in 1895, he became the secretary to the board of trustees in 1898 concurrently. In 1915, he added another duty—secretary of the university. Thus, Cravens played a key role in gatekeeping for the student body and witnessing trustee decision-making. As the trustee board authorized campus infrastructure driven by the needs of the student body, Cravens had access to relevant records of IU’s building program as he wrote Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University.

13

He started, not surprisingly, with the original Seminary Building on the old campus. Cravens intoned reverently: What a train of thoughts comes to one when he stands on the very site which marks the beginning of that institution destined to become in law and in fact

14 He went on to describe the process of choosing the site and the details of construction of the simple two-story brick structure, then launched into a description of the building’s uses over time and listed many of the early graduates who had made names for themselves. As the only academic building, it saw constant use from 1824 to 1836. When the larger College Building was finished in 1836, the older building was pressed into service as needs arose. It was torn down in 1858.the head of Indiana’s public-school system.

One feels that he should stand here with uncovered head. San Salvador, Plymouth Rock, and Jamestown each has its special significance. Each was the beginning of an important movement. The Old Seminary Building is the cradle of higher education in Indiana.

Cravens was attempting a word portrait, to fix in the reader’s mind the primordial significance of the structure that was the first physical embodiment of the idea of Indiana University. The trouble was, he admitted, the exact location of the Old Seminary Building had passed from the memories of the oldest graduates and citizens of Bloomington

in the two-thirds of a century since it was demolished. People remembered it was

15 Undeterred, Cravens got permission and a crew of men to excavate for any remains of the original building.on the high ground near the southwest corner of the old campus,

but all outward traces of the building had disappeared.

Charles Hays, the assistant superintendent of buildings and grounds, was the foreman.16 In addition to the university work crew, a group of older residents of Bloomington served as location consultants, including Hays’s father-in-law, who pointed to a spot within fifteen feet of where the old building had stood. They discovered the ruins of the Seminary Building, unearthing part of the foundation and entrance steps, and found the base of the College Building, which was constructed in 1836 and destroyed by fire in 1854. They marked the location with a stone and considered the construction of a suitable monument.17

In his second article, Cravens covered the remaining six buildings on the original campus—the professor’s house (1824–1864), the College Building (1836–1854), the Boarding-House (1838–1864), the Laboratory Building (1840–1858), the second College Building (1855–present), and Science Hall (1873–1883)—with details of construction and use.18 He delineated the trustee board’s debate after the fire that destroyed Science Hall in July 1883, about whether to rebuild on the seminary site. In September 1883, the trustees entertained seven sites, including the existing campus, ranging from ten to fifty acres. After discussion, a test vote was taken, with three favoring the present site, three for the Blair property (located northwest), and one for the Dunn property (located east). After further debate, the final vote was taken, with five for Dunn’s Woods and three for the existing site. Cravens summarized: And thus our present magnificent campus, recognized as one of the finest in the United States, was selected.

19

Cravens then went on to recount the story of the first buildings on the new campus in the third article, starting with Wylie Hall and Owen Hall, that eventually formed three sides of a quadrangle on the crest of the campus proper.

20 He enumerated in order of construction the seventeen buildings and structures that populated the campus in 1922, nearly thirty-five years after the move to Dunn’s Woods. He noted that all except two of the trustees who engineered the relocation were deceased. In each of the capsule histories, Cravens gave a myriad of architectural, construction, and financial details, in addition to the naming of the building, whether functional (Power Plant No. 1 or Student Building) or honorary (Maxwell Hall or Kirkwood Observatory). The result was a trove of rare information, combining data from records but also from campus lore and personal observation. The article ended with the newest building, the Commerce and Finance Building, for the use of the recently founded School of Commerce and Finance, which was still under construction in 1922.21

Cravens’s series, coming on the heels of IU’s centennial in 1920, was a unique compendium of campus architectural and social history. It married the old and new campuses in a straightforward chronicle of institutional progress, in which the devastating fires on the old campus served as an impetus for the relocation and led to brighter prospects for the university. The hidden variable in this focus on the physical plant was an exponential increase in the size of the student body, from less than two hundred at the start of the 1880s to nearly three thousand in 1922, with a concomitant expansion of faculty and staff numbers. The escalating growth of the campus infrastructure was also a result. Not only did Cravens’s articles draw attention to this formative period of campus development in its material embodiment, but they were also a refreshing complement to the exclusive focus on educational philosophy, policy, and practice that was found in the Centennial Memorial Volume published in 1921.22

5.3 Literary Appreciations

As enrollments kept rising through the 1920s, from 2,300 to 3,500 students, a remarkable efflorescence of prose occurred among students that featured the Bloomington campus. Whether addressing their remembered or present experience, student writers described the weather, the trees, and the buildings and pathways, thus evoking the university’s unique spirit of place. Some evidenced a deep attachment to place; others used the campus as a setting to describe personal feelings or states of mind.

Ernie Pyle, a columnist and editor for the Indiana Daily Student, penned a paean to IU’s spirit of place as students were returning to classes for the 1922 fall semester:

Nearly everyone who has ever attended Indiana University will tell you there is no place in the world like Indiana. They sometimes attempt to explain that statement but they cannot. When they ejaculate that there is no place in all the world like Indiana, they are thinking about something else. They are thinking about spring days when the campus is bursting with fragrance, vivid with color of blossoms and new leaves, and then the moon is bright—it is undeniable that spring is nowhere in the world as it is at Indiana. They are thinking about autumn evenings when dusk has settled.

Moving from the ambiance of nature to the human milieu, Pyle observed the deep interpersonal attachments the college experience fostered, continuing: They are thinking about hundreds of wholesome, pleasant people, who were their friends. They are thinking something about Indiana which none of them could ever express in words. These persons who make such broad unqualified statements about Indiana say that they have since tried living in many other places but somehow that tang is missing.

23 Trying to grapple with an ineffable spirit of place, Pyle showed glimpses of his gift for description and his penchant to take the ordinary universals of life as his subject.

Another student of the 1920s shaped by his time on the Bloomington campus was Hoagy Carmichael, who wrote about the main student hangout in a memoir. Located across the street from the campus, the Book Nook, a former bookstore turned into a soda fountain, was the hub of all student activity

in the days before the Indiana Memorial Union.24 Carmichael later recalled the teeming social life—indelibly associated with the composition of Stardust

—contained within:

On Indiana Avenue stood the Book Nook, a randy temple smelling of socks, wet slickers, vanilla flavoring, face powder, and unread books. Its dim lights, its scarred walls, its marked-up booths, unsteady tables, make campus history. It was for us King Arthur’s Round Table, a wailing wall, a fortune telling tent. It tried to be a bookstore. It had grown and been added to recklessly until by the time I was a senior in high school it seated a hundred or so Coke-guzzling, book-annoyed, bug-eyed college students. New tunes were heard and praised or thumbed down, lengthy discussions on sex, drama, sport, money, and motor cars were started and never quite finished. The first steps of the toddle, the shimmy, and the strut were taken and fitted to the new rhythms. Dates were made and mad hopes were born.25

Carmichael, a Bloomington native, had a special feel for his home in a college town. In his first, impressionistic memoir, published in 1946, he described the campus as he remembered it in the 1920s:

A low stone wall borders the campus on the south. This is the

spooning walland it is usually dotted by quiet indiscernible couples late at night who have stopped there on the way home from the Book Nook or a picture show. To the north of the campus, bounding Dunn Meadows [sic] and the old athletic fields, runs the famous Jordan River. Famous because of its high-sounding name and yet its waters—a foot deep in floodtime—barely trickle during the dog days of August.26

Tinged with nostalgia about times past, more wistful than sentimental, Carmichael’s writing was retrospective as he recalled his Bloomington roots years later.

For the first time, the campus woodland was the setting for a novel. Published in 1925, the novel Initiation was written by George J. Shively, a member of the class of 1916 who majored in English.27 A coming-of-age story, much of the action took place on university grounds under a fictionalized name for the institution. The Vagabond, the campus literary magazine, enthused: For the first time Indiana University lives under its own name and at full length in modern fiction. The veil is frankly not drawn over reality by calling the place Monrovia College and renaming Jordan Field. It deals with Indiana University more openly than does the University catalogue. Any student or alumnus knows where he is…. It is by far the best description of student life so far written about the school.

28

Following graduation, Shively went to Yale University to pursue literary studies, but after a year, his graduate program was interrupted by the Great War in Europe. He served in the Yale ambulance unit with the French Army during the war, where he was wounded. His first publication, a concise history of his ambulance unit, came out in 1920.29

Initiation was his second publication. As described in the novel, his recollections of IU campus life were fresh and vivid, tinged with longing for a more innocent time:

Upon John grew that affection which no one can escape who walks long under campus trees; that naïve and sentimental fondness at once fatuous and deep, that clings to a man long afterward, and that has been known, of mention of Alma Mater, to show up soft in gnarled citizens otherwise hard-shelled as the devil himself. To a peculiar degree the Indiana milieu was created to inspire love. It has the unspoiled generosity, the frankness, the toil, the taciturn courage and the exasperating ineptness of natural man himself. One listens to the winds sighing through beeches, or plods through autumnal drizzle with gaze divided between the cracks of the Board Walk and that miraculous personal vision that for no two people is produced alike, whether it be conjured from books, or from inner song, or from liquor, or from a co-ed’s smile or from all together. Because of this one berates Indiana and loves her doggedly.30

Shively went on to publish one other novel, Sabbatical Year (1926), a saga of an upper-class American family, before making a career in the publishing industry as a senior editor at Doubleday & Company in New York.31

In 1929, writer and humorist Don Herold penned a remembrance of his student days. Originally from Bloomfield, in a neighboring county, Herold graduated in 1913. He stated:

It is hard not to get soft about the Indiana campus. I know of none in America which surpasses it in beauty. Indiana buildings, some good, many architecturally atrocious, have been set in a forest of fine old trees, as the real estate agents would say. No adolescent saplings these, but grand old patriarch timber to touch the souls of sensitive boys and girls. I think the really worthwhile college student is a bit sad, and I feel that every campus should offer the comfort of towering trees. I am glad I did not have to go to college in a skyscraper or on a sun-baked subdivision. Romance burns best on a wooded campus. It would take a pretty generous state appropriation to offset the thrill of a stroll on the board walk from Kirkwood Hall to Forest Place…. As I said to myself a lot of times, say I,

I like this campus,and I know every other Indiana undergraduate has had many a similar throb.32

Such literary appreciations describe the emotional pull of the campus, heightened by campus society and the developmental challenges of learning and study.

Other students, less self-consciously literary, left their impressions as well. When Eura Ann Sargent, from Indianapolis, came to IU as a first-year student in 1927, the campus was largely as Cravens described it a few years before. The physical plant consisted of about a dozen academic halls arranged around three sides of Dunn’s Woods, plus the old Assembly Hall, power plant, and the new Men’s Gymnasium. All except the new gymnasium were adjacent to the woods. She remembered:

The campus was a thing of beauty. All around the Well House to the street was colorful woods. The sun had to force its way through the dense foliage and soft breezes stirred the leaves to make lazy ephemeral shadows on a ground carpeted with some of last year’s leaves and dotted with a few wild flowers and other stirring sprouts which dared to live in spite of the shade. Behind most of these ten buildings was picturesque and natural growth. Nature seemed to be pleased to have such latitude and was doing her utmost to make the best of the opportunity.33

Sargent joined generations of students who responded to the beauty of the campus and the intermingling of stone buildings and the woodland.

Among those responsible for the physical plant in those times was Charles Hays, then assistant superintendent of building and grounds. He not only supervised the groundskeepers but also tried his hand in landscape design. Because bedrock was located close to the surface in Bloomington, there were small-scale limestone quarries dotting the area. One was on campus near Third Street, west of Memorial Hall, sometimes called Dunn Quarry.

In 1928, Hays designed a rock garden within the old quarry, featuring a pond and attractive landscaping. The Sunken Gardens became one of the most beautiful spots on campus,

and the classes of 1927 and 1928 contributed money for supplies.34 A local resident vividly remembered playing there as a child:

It is still a refuge, a playground, a Paradise. Two arches in a low stone wall invite entry to descending flights of rough, shallow steps. These are bordered by trees, ferns and ground cover plants which hold the cool, dark, damp atmosphere born of the wide pond at the foot of steps. Circling the pond, the questing child arrives at her goal—the huge, sloping limestone rock which juts into the water. The rock’s surface, about two feet above the water, is superbly placed for watching crawdads and water striders, and is itself studded with fossils. The cool quiet of the Sunken Gardens was then, and is now, that child’s safe haven.35

Heavily used by sunbathers, swimmers, and artists, it was also favored by college sweethearts, leading to its popular name, the Passion Pit. For over two decades, the gardens provided a tranquil and picturesque setting for communing with nature until they were removed to make way for the construction of Jordan Hall (now Biology Hall) in the early 1950s.36

In 1929, alumna Edith Hennel Ellis, a member of the class of 1911, authored an article about the woodland campus for the Alumni Quarterly. Simply titled The Trees on the I.U. Campus,

it included poetic descriptions: Certain scenes stamp themselves indelibly upon the mind: lingering shadows of tall trees creeping across the grass on long summer afternoons; black trunks of trees rising from snow-covered slopes, etched against a leaden winter sky; masses of Forsythia bursting into sudden yellow bloom; and that loveliest of all Indiana springtime pictures, white dogwood and pink redbud blooming against a green background of maples.

Ellis asserted: The Indiana University campus is famous the country over for its natural beauty. It is more than a thing of beauty. Its trees are sanctuaries under which old men may dream dreams and young men may see visions.

37

5.4 Campus Development in the 1920s and 1930s

The landscape architectural firm of Olmsted Brothers began consulting with the IU administration in 1929.38 They prepared site plans for proposed buildings, laid out paths and streets, and advised on landscape design and planting schemes. They also carefully inventoried trees and vegetation in Dunn’s Wood, with a blueprint of location, species, and size. Like before, IU officials used the plans as guidelines and suggestions, modifying their implementation according to available finances and current priorities.

After the Men’s Gymnasium on Seventh Street opened in 1917, other new buildings sprang up during the 1920s. The first was on the quadrangle: the Commerce Building (now Rawles Hall), completed in 1923, due east of the Biology Hall (now Swain Hall East) on Third Street. To mark a primary entrance to the building, the class of 1926 donated funds for a pair of limestone pillars on the sidewalk adjacent to Third Street. In 1924, a campus home for President Bryan and his wife, Charlotte Lowe Bryan, was constructed. It was east of the quadrangle, along the campus border, on a slight rise between two small creeks. It was known as the President’s House (now Bryan House).

It was the last construction project overseen by Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds Eugene Kerr, who died in July. The Indiana Daily Student noted Kerr’s passing: For the last twenty years this man has labored earnestly for the good and advancement of the University. He has been instrumental in bringing about many of the needed improvements in buildings and grounds during that time. He took deep pride in keeping the buildings and grounds in the best of condition, and largely through his efforts the campus still ranks as one of the most beautiful of any college or university in America.

39 After Kerr’s death, Charles Hays stepped into the role of superintendent of buildings and grounds and served from 1924 to 1937. A few months later, Kerr was memorialized by a bronze plaque placed in Maxwell Hall.40

Also in 1924, the first dormitory for men, South Hall (now Smith Hall), was opened on Tenth Street, colonizing yet another street for the campus building program. It was joined the following year by Memorial Stadium (now Cox Arboretum) to the east. Across campus on Third Street, the first dormitory for women, Memorial Hall, was finished in 1925. It was no accident that living quarters for women and for men were on opposite ends of campus. In 1928, athletic facilities were boosted by the construction of the huge Fieldhouse (now the Garrett Fieldhouse), attached to the Men’s Gym, suitable for intercollegiate sports.

Despite the stock market crash in 1929, campus construction continued. That year, the power plant was renovated after a fire and finally made adequate.41 The class of 1929 funded a set of limestone gates along the campus border on Third Street, between Biology Hall (now Swain East) and Commerce Building (now Rawles Hall).42

In 1931, the long-planned Chemistry Building was completed. The large and handsome limestone building, decorated with a bold frieze depicting the elements of the periodic table punctuated with clusters of grapes, occupied a site due east of Wylie and Kirkwood Halls, outside of the quadrangle. The well-used amphitheater, the location of many commencement ceremonies and convocation programs, had to be sacrificed to make room for the new building, although one can still see the remnants of the natural ravine near the north entrance.43

The last of the facilities financed by the Memorial Fund was the Indiana Memorial Union (IMU). Formally dedicated at commencement in June 1932 with an inaugural dinner in Alumni Hall, the building was located south of Jordan River and north of Maxwell Hall, a few steps away from the quadrangle. Richly ornamented limestone carvings embellished the exterior, and the main Romanesque tower rivaled the tallest building in downtown Bloomington a few blocks away. In the lobby, a bronze tablet in the floor depicted the different branches of the military services of the IU men and women memorialized by the building and the Golden Book listed the names of those who served as well as the contributors who donated to the Memorial Fund drive. (Since 1961, the bronze tablet and the Golden Book have been located in the Memorial Room, an antechamber off the lobby.) The east wing was allocated for the university bookstore, which featured a second-floor balcony and lounge with a fireplace. Taken with the graceful luxuriance of its utilitarian design, President Bryan boasted that it was the most beautiful college bookstore in America.

The bookstore manager, Ward G. Biddle, became the first director of the Indiana Memorial Union. Almost immediately, the union became an essential part of campus life as well as an iconic architectural landmark.44

Two months following the IMU dedication, the national economic situation caught up to the Hoosier economy, and the Indiana General Assembly cut Indiana University’s budget request by 15 percent. Soon after, the Bryan administration authorized faculty salary reductions ranging from 8 percent to 12.5 percent. President Bryan, who insisted on an even higher cut to his own salary, received expressions of gratitude from the faculty that the reductions were not higher.45

It was years before the situation improved. In 1935, the university presented a budget to the state of just under $1.5 million, which was met with success, accompanied by a supplemental request of $335,000 to address deferred needs, which was not. The next year, President Bryan prepared the budget request, noting that salaries had not been restored after the 1932 cut. The state granted $1.9 million in 1937, about 15 percent less than the request, and did not fund the requested $500,000 for capital projects.46

The federal government, under President Franklin Roosevelt, had several relief agencies operating during the 1930s to assist in providing funds for public works, notably the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA, later Work Projects Administration). Revising previous lists of building needs, in 1935, the trustees sought federal assistance for an extension of the power plant, another women’s dormitory, and buildings for the music school, education school, university administration, and one each for the medical school in Bloomington and in Indianapolis. The state government, under Governor Paul McNutt, former dean of the IU School of Law, assisted in obtaining financing.47

As the trustees prepared to finance construction of a new administration building in 1935 with the aid of WPA funds, they decided to put it east of Kirkwood Observatory and north of Fourth Street—right in the center of the woods.48 Students got wind of this plan and expressed their misgivings through the editorial columns of the Indiana Daily Student newspaper. There was general concern that it would mar the natural beauty of the campus. Zoology professor Alfred Kinsey sided with the students opposing the plan, but English professor William Jenkins supported placing the building in Dunn’s Woods.

The newspaper published each of their statements in full. Jenkins cited the opinions of experts, arguing that every survey of the campus by qualified landscape architects has put the building on that site.

He thought most people could imagine seeing the gray limestone structure half hidden by the trees from Maxwell Hall. Besides, he thought, it was a common error to think that forest trees are desirable near a formal building. As a matter of fact such a building should have formally treated grounds about it,

he concluded. Kinsey, who was an accomplished botanist as well as a zoologist, drew an analogy: From a landscape standpoint it is better that the center of the campus be kept clear of buildings for the same reason that the center of a lawn should be kept clear of shrubbery and flower beds.

He reminded readers that the central quadrangle, under development for a half century, had been framed on two and a half sides with perimeter buildings. The heart of the picture is the growth of trees which has made our campus famous all over the country.

Barring some new comprehensive plan, he argued, new buildings should be placed to complete three or four sides of the picture without modifying the present center of that picture.

49

The concerns of students and faculty resonated with the trustees, and they relocated the plans for the administration building to the corner of Indiana and Kirkwood Avenues, due south of the library, making a start on the fourth side of the quadrangle’s framing.50 The administration building, officially named for President William Lowe Bryan in 1936 at the urging of Governor McNutt, was called by its generic name because PWA rules prevented the use of Bryan’s name during his lifetime.51 The class of 1935 provided funds for limestone benches on the first and second floors.52

In 1937, three new buildings were completed: a women’s dormitory (Goodbody Hall), placed at right angles to Memorial Hall, and the School of Music Building (now Merrill Hall) and the Medical Building (now Myers Hall), both along Third Street. The next year, the Clinical Building of the School of Medicine was completed in Indianapolis, and the School of Education Building, including a laboratory school, University School, was finished, located at the corner of Third Street and Jordan Avenue, anchoring the growing line of university buildings on Third Street stretching westward to Indiana Avenue.53

5.5 Beneath the Sundial

Amid this forward-looking expansion, pieces of the campus’s past also sprung up. Otto and Mathilda Klopsch were both members of the class of 1896, the year the sundial was relocated from the old campus to Dunn’s Woods. They had fond memories of the woodland campus and reminisced about their time at IU with their three children. In 1935, after both had died, their son Otto Jr. requested and received permission from President Bryan to scatter their ashes at the base of the sundial. Their children made a wish: May their spirit rest as peacefully as it lived happily while they studied and loved on these grounds.

A bronze plaque at the sundial’s base was inscribed:

Mathilda Zwicker Klopsch / Otto Paul Klopsch / Class of 1896

They met at this sundial when classmates.

Their ashes rest here together until eternity.

This memorial joined Dunn Cemetery as a consecrated place of memory on the IU campus.54

Keeper of Grounds William Ogg turned eighty in 1931 but continued working throughout the decade. In 1936, President Bryan lauded Ogg as a master of the fine arts of dealing with all things that grow upon our glorious campus

for the previous thirty-five years: Dealing rightly with plants is Art.

55 In 1938, Ogg finally got out of the weather and became the greenhouse man,

with his salary line transferred to the Department of Botany.56 He retired the following year, at eighty-eight. Although Ogg was the senior figure of the groundskeeping staff, many others contributed years of dedicated work in caring for the IU landscape.

5.6 A Vision Realized

President William Lowe Bryan gave notice of his retirement in March 1937, after serving thirty-five years, longer than any of his nine predecessors. His foresight and discernment helped guide the university through a time of tremendous growth. The student body increased from 750 in 1902 to 5,000 in 1937. During his administration, the basic structure of graduate and professional education was established, with the organization of the schools of medicine, education, nursing, business, music, and dentistry as well as the graduate school and the extension division.

The physical plant had undergone significant expansion too, as the campus footprint increased from 50 acres in 1902 to almost 140 acres in 1937. The crescent of buildings at the northeast corner of Dunn’s Woods in 1902 had, by 1937, developed into a four-sided frame enclosing the woods, reminiscent of an oversize Gothic quadrangle. President Bryan, who had been a student at the Seminary Square campus and started his teaching career during the transition to the Dunn’s Woods campus, was a champion of letting the natural beauty of the woodland shine. His vision of the venerable quadrangle as the heart of the campus was realized, even as growth pushed campus boundaries ever farther.

Bryan’s successor as president was the dean of the School of Business Administration, Herman B Wells, who was a 1924 IU graduate. His nine-month stint as acting president started in July 1937. By March of the following year, Wells was confirmed as IU’s eleventh president, a position he would hold for the next quarter century.

As a student in the early 1920s, Wells participated fully in campus life, both academically and socially, and first knew the campus when it was organized around the Dunn’s Woods quadrangle. Wells later recalled his student years as a time of response, growth, transformation, and inspiration.

The natural environment was key: My senses were so keen that they eagerly absorbed the beauty of the changing seasons in southern Indiana, the pastel colors of spring, the drowsy lushness of summer, the brilliance of the fall foliage, and the still but invigorating atmosphere of winter.

57

In the early 1930s, he became a junior faculty member and witnessed the growth of the campus beyond the quadrangle. In August 1937, Charles Hays, superintendent of building and grounds, died of a heart attack at only sixty-one years old. He worked for IU for thirty-one years, working his way up from custodian for Kirkwood Hall to the directorship of the physical plant. The Alumni Quarterly stated, Mr. Hays was responsible for much that is pleasing on the campus, and especial mention should be made of the sunken garden near Memorial Hall, made in an old quarry hole. Students will remember his work in arranging stage settings for revues, and in devising decorative effects for social affairs.

58 Both President Emeritus Bryan and Acting President Wells gave brief public statements. Bryan, who had worked with Hays for three decades, summarized, He was devoted to Indiana University, and never spared himself in its service. I counted him as a true friend and he never failed me.

Wells said, Charlie Hays has a living memorial in the Indiana University campus. For many years he has been quietly at work enhancing its beauty without disturbing its naturalness.

59

As president, Wells continued to honor the timeworn elements of stone, water, and trees as the foundation of campus design. He was attuned to how the buildings and grounds could enhance learning as the campus was poised for exponential growth in size, programs, and students.60

“History of University Land Purchases,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 2 (1915): 159; land purchases are summarized in Burton Dorr Myers, History of Indiana University: Volume II, 1902–1937, The Bryan Administration, ed. Burton D. Myers and Ivy L. Chamness (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1952), 755.↩︎

A Hoosier Holiday (New York: John Lane Company, 1916), 503. He was referring to Mitchell Hall as the former library.↩︎

Lee Ehman, “The Dunn Name, but Not the Spirit,” Monroe County Historian 3 (August 2010): 10–11.↩︎

Quoted in J. Terry Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington: America’s Legacy Campus (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), xx, from Theodore A. Brown and Lyle W. Dorsett, K.C.: A History of Kansas City, Missouri (Boulder, CO: Pruett, 1978), 163–164.↩︎

“Letter to George Kessler” (Indiana University Archives C286/B150/F Kessler, George, May 25, 1916).↩︎

“Straightout Americanism,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 5, no. 3 (July 1918): 295–307.↩︎

James H. Capshew, Herman B Wells: The Promise of the American University (Bloomington; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press; Indiana Historical Society Press, 2012), 27.↩︎

Capshew, 27–29. The IMU now owns over seventy paintings of T. C. Steele.↩︎

John W. Cravens, “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University: I. The Old Seminary Building,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 9, no. 1 (1922): 1–11; John W. Cravens, “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University: II: Six of the Buildings on the Old Campus,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 9, no. 2 (1922): 156–64; John W. Cravens, “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University: III. Buildings on the New Campus and Elsewhere in Monroe County,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1922): 303–20.↩︎

Cravens, “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University,” 1922, 1.↩︎

Cravens, 3. Original emphasis.↩︎

Charles H. Hays (1897–1937) was a native of Monroe County and spent a thirty-one-year career at the university. Starting in 1906 as a custodian for Kirkwood Hall, he became assistant superintendent of buildings and grounds in 1917. After being promoted to superintendent at the death of his predecessor, Eugene Kerr, in 1926, he served until his sudden death from a heart attack in 1937. President Bryan noted his artistic interests, which took various forms: scenery manager for student plays, decorator for university events, and campus landscape designer. See “Charles H. Hays,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 24 (1937): 511–12.↩︎

“Discover Ruins of Seminary Building,” Indiana Daily Student, January 18, 1922, 3. See map in Cravens, “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University,” 1922, p. 161.↩︎

The second College Building, sometimes referred to as the first University Building, was sold to the Bloomington school system in 1897 and served as Bloomington High School until 1965, when a new school was opened at 1965 S. Walnut Street and the former IU building was razed.↩︎

“Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University,” 1922, 164.↩︎

“Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University,” 1922.↩︎

Cravens, 319–20. The Commerce and Finance Building was renamed William A. Rawles Hall in 1963 by the trustees.↩︎

Ivy L. Chamness, ed., Indiana University, 1820–1920: Centennial Memorial Volume (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1921).↩︎

Ernie Pyle, “It’s in the Air,” Indiana Daily Student, September 5, 1922, 4.↩︎

Herman B Wells, Being Lucky: Reflections and Reminiscences (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), 33.↩︎

Hoagy Carmichael and Stephen Longstreet, Sometimes i Wonder: The Story of Hoagy Carmichael (New York: Farrer, Straus; Giroux, 1965), pp. 54–55. To sort out the folklore surrounding the composition of

Stardust,

see Richard M. Sudhalter, Stardust Melody: The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 103–123.↩︎Hoagy Carmichael, The Stardust Road (1946; repr., New York: Greenwood Press, 1969), 34.↩︎

George J. Shively (1892–1980) was the son of Benjamin Franklin Shively (1857–1916), a US senator (1909–16) and IU trustee (1893–1916) who served as president of the board from 1906 until his death. He died on March 14, 1916, when his son George was weeks away from IU graduation.↩︎

F. C. S[enour], “A Novel of Indiana University,” The Vagabond 2, no. 3 (March 1925): 51–52.↩︎

George J. Shively, ed., Record of S.S.U. 585 (New Haven: Brick Row Book Shop, 1920).↩︎

George Shively, Initiation (New York: Harcourt, Brace; Company, 1925), 122.↩︎

Sargent interview, in IU Archives reference file

African Americans at IU. William Smith’s Research Files for the

Sargent was among the tiny minority of African Americans at IU during this period, about 1 percent.↩︎African American Experience at IU

Project.Myers, History of Indiana University, 381; “Charles H. Hays,” 1937; “Charles H. Hays,” Indiana Alumni Magazine 19, no. 7 (1957): 1.↩︎

Sue Davis Gabbay, “Letter to Brad Cook” (Indiana University Archives/Reference file: B+G Sunken Gardens, March 2013).↩︎

Edith Hennel Ellis, “The Trees on the I.U. Campus,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 16, no. 3 (1929): 331.↩︎

In 1898, John Charles Olmsted (1852–1920) and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (1870–1957) formed the Olmsted Brothers partnership, operating under that name until 1961. See Olmstead Firm.↩︎

Quoted in “Death of Eugene Kerr,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 11, no. 4 (1924): 544.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 13 March 1925–14 March 1925” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 14, 1925), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1925-03-13.↩︎

Indiana University Archives, “Reference File: Class Gifts” (Bloomington: Indiana University; Unpublished archival material, n.d.).↩︎

Myers, History of Indiana University, 418–19, 434–35; Robert E. Lyon, “The History of Chemistry at Indiana University, 1829–1931,” Indiana University News-Letter 19, no. 3 (March 1931).↩︎

Myers, History of Indiana University, pp. 413–417; Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington, pp. 266–271; The Golden Book↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 March 1935” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 4, 1935), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1935-03-04.↩︎

“Professors Take Divergent Views on Building Site,” Indiana Daily Student, March 28, 1935, 1, 3.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 April 1935” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, April 4, 1935), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1935-04-04.↩︎

Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington, 324; Gavin Lesnick, “Campus Icon Retains History, Myth from 1868,” Indiana Daily Student, September 13, 2005, https://www.idsnews.com/article/2005/09/campus-icon-retains-history-myth-from-1868.↩︎

Bryan quoted in “In Memoriam: William A. Rawles, ’84, Robert A. Ogg, ’72, William T. Patten, ’93; and Necrology List,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 23, no. 3 (1936): 309–10.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 November 1938–04 November 1938” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 3, 1938), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1938-11-03.↩︎

James H. Capshew, “The Campus as a Pedagogical Agent: Herman Wells, Cultural Entrepreneurship, and the Benton Murals,” Indiana Magazine of History 105, no. 2 (2009): 179–97, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27792978.↩︎