4 Establishing University Park

Places are fusions of human and natural order and are the significant centres of our immediate experiences of the world. They are defined less by unique locations, landscape, and communities than by the focusing of experiences and intentions onto particular settings. Places are not abstractions or concepts, but are directly experienced phenomena of the lived-world and hence are full with meanings, with real objects, and with ongoing activities. They are important sources of individual and communal identity, and are often profound centres of human existence to which people have deep emotional and psychological ties.

—Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness

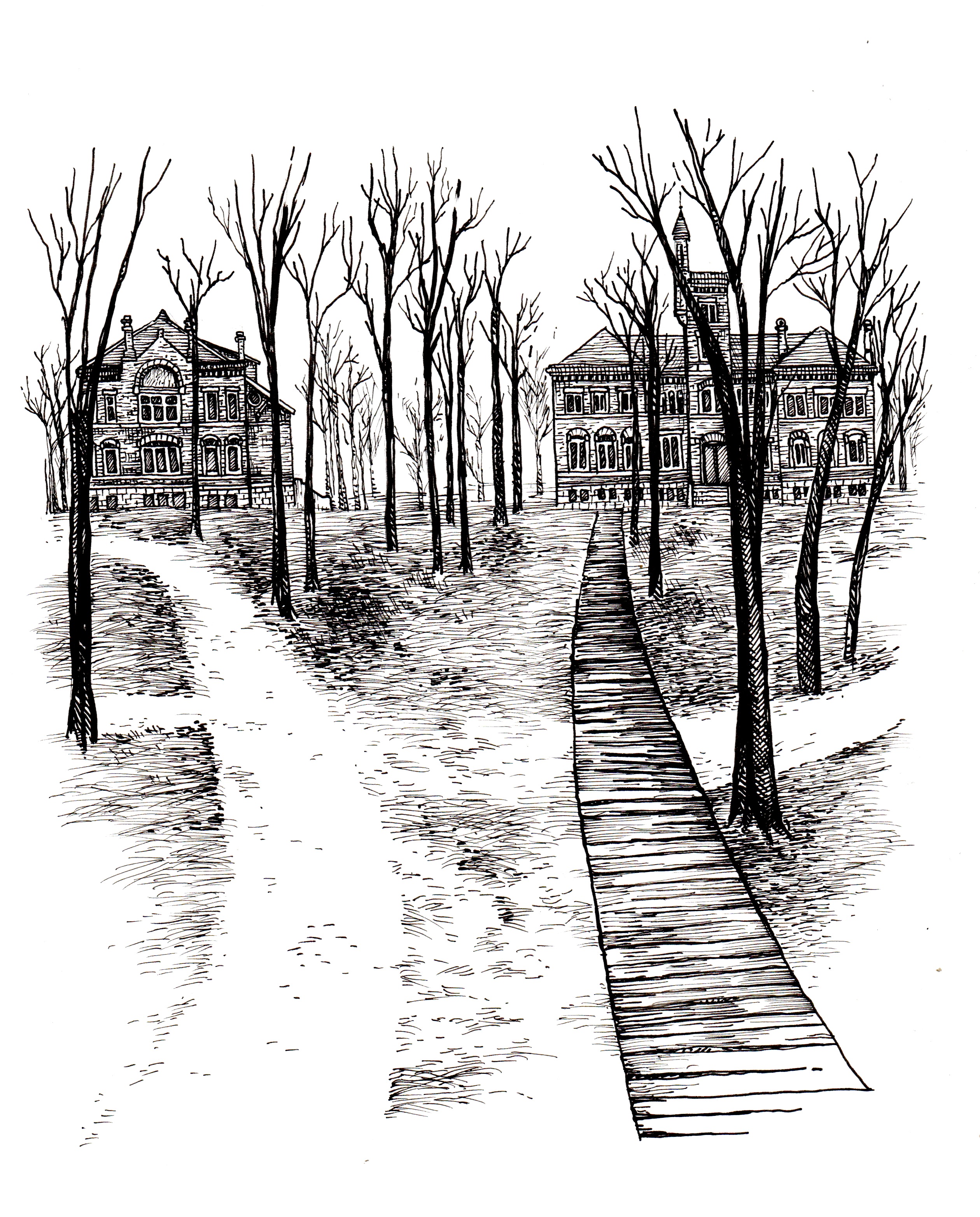

By the 1880s, Indiana University had occupied the Seminary Square campus for nearly sixty years. Carved out of the forest that was Bloomington in the 1820s, the campus had accommodated a succession of buildings that served the academic needs of the tiny collegiate institution. The ruins of Science Hall, destroyed in the 1883 fire, lay next to the College Building, itself rebuilt in 1855 after an earlier fire. The site had had hard usage and no attention was given to beautifying the campus,

but some trees and shrubs had sprung up on their own after the initial clearing.1

The IU Board of Trustees was pleased to be getting away from the dirty clatter of the railroad abutting the campus, away from the industrial machine and back into the peaceful quiet of the woods. Hoosier attitudes had changed since the Seminary Square campus was cleared of trees in frontier Bloomington. Six decades of increasing use of Indiana’s forests led to a growing realization that they were not an inexhaustible natural resource, and they deserved conservation for the future. In fact, one of Bloomington’s largest employers was the Showers Brothers Furniture Company, which made wooden bedsteads and other furniture.2 Overall, forests provided essential materials for shelter, fuel, and food, and their magnificent forms dwarfed any manmade structures until the mid-nineteenth century.

The contrast between Dunn’s Woods and the original site was stark, and the move was accompanied by a new appreciation of landscape beauty. Although wood still provided many of the raw materials for daily life, no longer was the forest regarded as an obstacle to civilizing forces, symbolized by a clearing in the wilderness. In a time of widespread deforestation in the state, now the presence of trees was seen as a welcome amenity, a moral counterweight to industrial society, where one could regain a measure of peace and equilibrium by contact with nature. The university’s recent purchase was not virgin forest by any stretch, but the unimproved farm woodlot did have mature trees that prompted an aspirational designation as University Park

by the trustees in June 1884.3

The ideas of Frederick Law Olmsted, landscape designer of Central Park in New York City, were spreading around the nation, including to universities and colleges. It was his belief that the location and design of the campus played an essential role in the students’ educational experience

of equal importance with the academic curriculum: The properly designed campus was part of the civilizing mission of the college or university, educating the taste and sensibilities of students.

4

The new site contained twenty acres of a gently sloping hill, generally oriented west toward the town, with a small brook. Before the university acquired the land, it was used by local townspeople chiefly for the practice of outdoor speeches, solitary strolls, and clandestine meetings

with the tacit approval of the property owners.5 Decisions were made to construct the principal buildings toward the back of the lot, in the northeast corner, oriented at right angles to each other and to have their main entrances facing the woods. Two halls were built of brick recycled from the ruins of Science Hall, and a smaller wood-frame building completed the initial tableau. In keeping with the thirty-year tradition of employing consulting architects, the university hired Indianapolis architect George W. Bunting to design all three.

Ground was broken in spring 1884, and by June, the trustees had chosen building names. The larger of the brick buildings was designated Wylie Hall, in memory of the first president, Andrew Wylie, and in honor of Theophilus Wylie, a longtime professor. A plaque of gratitude for the financial aid from Monroe County was to be placed in the interior.

The other brick structure was named Owen Hall, for the brothers Robert Dale Owen, David Dale Owen, and Richard Dale Owen, sons of social reformer Robert Owen, famous for a utopian social experiment in New Harmony, Indiana. Still living, Richard was a retired IU professor of natural sciences. His brothers, both deceased, had achieved prominence in their careers.6

Given the university’s poor financial situation, the trustees simply desired to replicate existing programs and facilities on the Dunn’s Woods campus, albeit with new buildings. With the increasing interest in scientific subjects and their demands for laboratory and museum space, Wylie and Owen Halls were devoted to science.

The Student newspaper described the remaining structure: The third, a poor little frame, is used for chapel; [and] stored away in its attic are four or five little rooms, about 12 x 16, where the student must get his philosophy, political economy, literature, languages, & etc.

7

The city of Bloomington was supportive of the site of the new campus and desired to honor the most distinguished member of the faculty in March 1884: Since the location of the new University buildings have been known, the citizens, and especially those on 5th street, have been talking of naming that thoroughfare Kirkwood Avenue, in honor of our distinguished townsman, Prof. Kirkwood. Last Friday night a petition was properly presented to the Council, and by a vote the name was so changed. The new University buildings now front on Kirkwood Avenue, if you please.

8

Soon after campus was opened for classes in 1885, the setting of University Park was highly praised by a local newspaper: The forest trees in the new college campus now present a scene of true magnificence. Never was there a lovelier scene than the one presented there last Sunday October 1885. It was a lovely Indian summer day, and the earth, the air, the clouds, the sky, and the roseate tints of the stately forest streets seemed to vie with each other in presenting a scene of gorgeousness never excelled by nature.

9

The contrast between the old and the new campuses became a theme that would resonate and provided a temporal marker of IU history—that is, before or after the move to Dunn’s Woods.10

4.1 A Sylvan Park

By 1888, after the initial flurry of construction, the trustees wanted to improve the grounds in University Park. To remedy the muddy dirt paths on campus, brick walks leading into the campus and to the buildings were in place by the summer of 1889, and boardwalks were elevated over the low ground in the woods.11 For advice on planning, they contacted landscape architect Olof Benson, who had been involved in the design of Chicago’s Lincoln Park, and arranged a site visit.12 He spent over a week mapping out the twenty-acre campus and submitted a planning sketch and a report.13

Benson, in keeping with the idea of working with nature popularized by Olmsted and his design of Central Park in the 1850s, extolled the native trees growing on the old farm woodlot. Taken by the charm of graceful groves of round-headed trees on gracefully sloping hillsides,

he advised prospective landscape gardeners to highlight the characteristics of a place and enhance its beauties.

He urged protecting the green space for the future: Everything should be in keeping with the

14 He went on to give further suggestions, like planting evergreens as a backdrop to the large deciduous trees.Stately Groves.

Nothing should be planted on the grounds, either buildings or trees, that will belittle these Patriarchs of the Forest.

Benson’s written report was accompanied by a beautifully rendered hand-drawn, colored sketch of the campus, with potential building sites, walkways and roads, and planting areas identified. A large plot next to Wylie Hall was deemed a suitable site for the main university building, a couple of locations on Third Street were endorsed for buildings of manual training and a physical laboratory, and west of Owen Hall had space for another large building.15

Students appreciated the campus as well. In 1889–90, future author Theodore Dreiser spent a year at IU as an eighteen-year-old first-year student. He had been working in the smoky, noisy city

of Chicago before coming down to Bloomington where all was green and sweet.

He remembered:

The college campus, while it contained but a few humble and unattractive buildings, was so strewn with great trees and threaded through one corner of it (where I entered by a stile) with a crystal clear brook, that I was entranced. Many a morning on my way to class or at noon on my way out, I have thrown myself down by the side of this stream, stretched out my arms and rested, thinking of the difference between my state here and in Chicago.16

Although he did not continue as a student, his year on campus was restorative, and he reported, my outlook and ambitions were better.

17

Benson’s recommendations affirmed the wisdom of building on the perimeter of the plot. Soon a library building was planned to the west of Owen Hall. Completed in 1890 and named for the Maxwell family in 1894, it was a handsome and richly ornamented Richardsonian Romanesque interpretation of collegiate Gothic.18 Designed to hold the library, with its collections still being reconstructed after the 1883 fire, as well as the president’s office and some classrooms, the hall became a template for future buildings in its use of limestone for its exterior. Bloomington’s location within an extensive belt of high-quality limestone was a boon for the growing campus, providing an ideal building material that could be shaped for academic halls with Gothic features. The library interior featured richly textured native hardwoods fashioned into doors and window frames, stairs and balustrades, and partitions. About the only natural resource that traveled any distance was sunlight, which illuminated the interiors through skylights, transoms, and tall windows. The grounding presence of nature permeated the campus.

19 Shortly after Maxwell Hall opened, janitor Stuart received a raise and a budget to hire assistants as needed.20 Student enrollment continued to grow, and by the fall of 1894, it stood at 748.

The next limestone hall, named after Daniel Kirkwood and designed by Parker & Jeckel, an Anderson, Indiana, firm, was finished that fall. It stood next to Wylie Hall, lined up precisely in a so-called Yale Row, pioneered by Yale University, where the early buildings were arrayed in a line facing the town of New Haven’s common green. At the dedication in January 1895, professor of philosophy William Bryan spoke: This is Dedication Day and also Foundation Day. We cannot dedicate and forget the founders…. More directly we are indebted to our own people, to those who cut away these woods and built a schoolhouse almost as soon as they had built a cabin.

21

The campus, now consisting of five academic halls, was taking shape, oriented toward the seasonal green of the woods like an oversize Gothic quadrangle. But instead of four buildings enclosing a common lawn in the medieval design, IU was generating a picture frame of buildings around an expanse of forest. A consensus to conserve the woodland was already emerging in the academic community as the first corner of the building design was established.22 Ubiquitous in southern Indiana, trees were becoming valued for their aesthetic qualities in addition to their myriad practical uses. The Dunn’s Woods campus took shape as a ceaseless conversation between limestone architecture and the woodland landscape.

History was part of the conversation as well, both in discourse and in physical artifacts. The university started celebrating Foundation Day in 1889 at the suggestion of President Jordan. David Banta gave annual addresses from 1889 to 1894 on the history of Indiana University. In 1896, eleven years after the move to Dunn’s Woods, the old sundial from the Seminary Square campus was moved to the southwest corner of Maxwell Hall. Installed in 1868 near the main entrance on College Avenue and Second Street, the venerable timepiece was a point of central interest

on the old campus. The move was prompted by a suggestion from the Physics Department to better regulate the electric bells marking the beginning and ending of classes.23 The sundial came attached to an apocryphal story about President Cyrus Nutt (1860–75) consulting it at night by striking a match to see the time. During daylight, it served as a practical timepiece, although other means of time-telling gradually relegated it to the status of an heirloom souvenir of the old campus. That same year, a pair of gingko trees was planted along the walkway between Owen Hall and Maxwell Hall.24

4.2 Campustry: Romance in the Woods

The environment for learning was enhanced by the new buildings and surrounding landscape of Dunn’s Woods. The woodland was also conducive to extracurricular activities—including one that did not receive official sanction but was common throughout the student body and even faculty members upon occasion. Called campustry,

it was a discipline that most were eager to learn. It meant courting out-of-doors, romance under the trees, building personal relationships in the pastoral setting of the campus.

Campustry at IU began as soon as students encountered each other in the fall of 1885, and written descriptions started appearing in the 1890s. The combination of beautiful surroundings and increasing numbers of students provided a basis for its emergence. Not surprisingly, students wrote about it in the Arbutus yearbooks and in the pages of the campus newspaper, the Indiana Student, which offered Information for New Students

as a guide:

Campustry and chemistry are not the same science. Both offer chances of working, the law of affinity applies to both, both are experimental sciences, both include processes with varying results, in both many fragile articles are broken, but the first science is always more pleasant than the second, and is always more popular with the girls. A class in campustry consists of no more than two members, needs no oversight from the faculty, and recites on the campus. The only requirement for entrance is the prospect of a spring case.25

Campustry depended on an appreciation of the scenic value of trees and surrounding vegetation, something southern Indiana was known for. As the former farm woodlot—previously cut for firewood to feed fireplaces and stoves that were still ubiquitous in homes and businesses—was reimagined as a bucolic University Park, students and faculty alike reveled in the natural beauty.

In the 1899 Arbutus, a story described campustry as a synergy between human feelings and the natural environment:

The Indiana University campus is never more attractive than in May. It is then that the leafy, whispering boughs of the maples and sugar trees are most inviting for

campustry,that most fascinating pleasure of college life. The overworked Freshman and the worldly Senior alike finds it refreshing to lounge in the shade at a respectable distance from the recitation rooms in company of a fair maiden. Nothing will more effectively drive away the thoughts of the blunder made last hour or make one forget when the next recitation period begins. The visitor at this time of year will noticecases of campustryin all stages of development.26

Extravagant practitioners of campustry became the subject of stereotyping and the butt of humor, in similar fashion to college football players, fraternity members, or cheerleaders. An Indiana Student writer described some of the qualities of the stereotype, referring to a French nobleman who was in the news in the late 1890s:

There is one type of undergraduate that is more interesting and more widely known than any other. I refer to that happy-go-lucky individual who parts his hair down the middle and takes a cocktail on the side. He sticks a flower in his buttonhole and a cigarette in his face and imagines himself a superior of Count de Castallane [sic] or any other titled foreigner. He is sipping the joys of life and throwing out the dregs. He is a curious combination of saint and sinner, fool and philosopher. He spends fifteen minutes digging on his mathematics and thirty polishing his shoes. You ask him about his work, and he is driven to death. In the forenoon he attends recitations and takes campustry.27

Many of these romantic encounters were considered casual and flirtatious, but in some cases, they grew into serious relationships and even marriages. Instead of frowning on Campustry, the University management and faculty, with the result that for many years one-half of the faculty marriage have been the outgrowth of the

By 1903, the Daily Student reported that 68 percent of the IU faculty were married to Indiana girls.28college case.

Not all of the IU students at the turn of the century practiced campustry, however. For instance, in 1898–99, Carrie Parker, the university’s first African American female student, did not have time to cavort in the woods as she labored for room and board in the house of a professor and his wife. There were also reports of immoral students

in Dunn’s Woods.29

Although campustry proved to be a durable tradition for nearly a quarter century, it faded with the advent of collegiate sports, the rise of automobile transportation, and changing student fashion. Even the word campustry atrophied through disuse and eventually disappeared from collective memory.

4.3 Campus Planning and Design

In early 1896, David Mottier, a professor of botany on leave in Europe, wrote to his department colleague, Joseph Pierce, to discuss how the department might use a greenhouse for teaching and research, but he thought there was no need for an extensive botanical garden because of the natural setting of the campus. He added:

It is a pity, too, that the Trustees do not make an effort to annex the portion of woods just east of the campus. That would be a good place to transplant and prevent from becoming extinct many of the wild plants which must soon pass into history with the present destruction of the forests and their conversion in sheep pasture etc…. That the acquisition of the woods on the east to the campus as a part of this garden is a necessity and likewise their duty. I think that plot of ground with its matchless forest trees could be made the most beautiful campus in the country.30

Mottier, once he returned to campus, became an ardent proponent for the preservation of native plants for both their scientific value and their inherent beauty.

In the same year, President Joseph Swain hired Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot to get advice on further campus improvements. The firm, headed by the two sons of Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New York’s Central Park, and the son of Charles W. Eliot, the president of Harvard, was the most distinguished landscape architect partnership in America.31 Their twenty-three-page report started with five pages arguing that the university should purchase additional land for the campus now in preparation for growth. In other words it is better that the University should control more land than it actually needs at the time,

they wrote, rather than be crippled afterwards for lack of room, or rather than that it should be compelled to pay exorbitant prices for land when actually needed.

32

The report did not include a topographical map or architectural plans for specific buildings but presented a general overview of planning considerations for campus design. The recommendations included having one dominant building material, placing the administration building at the main campus entrance, lecture halls and laboratory buildings divided by function, a library that would have room to grow, specialized discipline collections rather than a general museum, conveniently located gymnasium and athletic fields, a botanical greenhouse and garden (not less than two or three acres and better ten or twenty acres

), and steam heating with central boilers and conveyed through dry tunnels. The report commented: It has not been the custom of our State Universities to furnish dormitories, but there seems to be no good reason why they should not be provided.

They recommended, if built, the dormitories should not be over three stories tall and have a domestic aspect

somewhere between a city hotel and a suburban villa.

33

Under the heading Water Supply,

the report stated, We understand that the present city supply is at times inadequate and not always attractive in appearance, if altogether wholesome.

They suggested drilling an artesian well supply to be pumped to a water tower, all under the direct control by the University,

and touted its value in case of fire. Care must be taken, they cautioned, to locate the tower away from campus.34

As far as vegetation, the general landscape character of the university should be that of a shady grove with the ground covered with turf only,

which would include shrubbery around building foundations. Concerned with the thinning of the forest by natural causes over the following ten to twenty years, they recommended planting replacement trees. Native trees were preferable for two reasons: they are better adapted to the climate and soil, and also because they look more appropriate.

35

The trustees received the report and took the advice to buy more land to heart. The next year, they purchased another thirty acres of the old Dunn farm, surrounding Dunn’s Woods on all but the south boundary of Third Street. The campus now extended to Indiana Avenue, Seventh Street, and what is now Hawthorne Avenue. The additional land extended Dunn’s Woods to the west, brought additional woodlands to the east, and included a creek—Spanker’s Branch—and a meadow to the north. The purchase included a growing giant burr oak and a large beech tree on opposite sides of the creek.36

By the end of 1897, the size of the campus had increased 150 percent, to fifty acres, leaving ample room to grow the 600-student university.37 Money to pay for new buildings would have to wait a few years, but tree planting and other landscaping efforts could be started immediately. And now the athletics teams had a convenient field, named Jordan Field in honor of the former president, to play sports rather than trekking to the athletics field on the old campus.38

Within this purchase area, the Dunn Cemetery, on the south bank of Spanker’s Branch, was excluded. Deeded for perpetual use as a family burial ground in 1855, the land was originally acquired by Samuel Dunn Jr. as part of a 160-acre homestead. The remains of three Revolutionary War heroines were buried here—Ellenor (Brewster) Dunn, who was Samuel Dunn Jr.’s mother, and her sisters, Agnes (Brewster) Alexander and Jennet (Brewster) Irwin. Old gravestones, grass, and a few trees gave the space, popularly known as God’s Little Acre,

the peace it deserved as the campus developed around it.39

With the increase in land area, janitor Stuart’s title was changed to superintendent of buildings and grounds.40 After a decade and a half of working, Stuart resigned in the spring of 1899, and the president and the trustees conveyed their appreciation of his long and faithful service

to the campus.41 That spring, William R. Ogg was among the workers hired to help with the physical plant.42 Ogg was the brother of Robert A. Ogg, who was serving as an alumni trustee.43 Like Stuart, he managed both buildings and grounds. Ogg performed all of the outside work by himself with only the aid of a wheelbarrow.

44

In May 1899, President Swain received a letter from Rudolph Ulrich, a landscape architect who was making his name working on gardens for national expositions around the country, offering his services.45 With the recent increase in campus size from twenty to fifty acres, the trustees hired Ulrich. He visited the campus and eventually produced a highly detailed sketch of his suggested building sites, roads and pathways, and other facilities. The campus site was square shaped, bounded by Indiana Avenue on the west; Third and Seventh Streets on the south and north, respectively; and Forest Avenue (now Hawthorne Avenue) on the east. The plan, produced in 1902, showed several sites for buildings that were eventually constructed around the edges of the quadrangle (Student, Science, Biology, Commerce and Finance) as well as two sites within the woods that were not used.46

The construction of the campus observatory in 1900, named for Daniel Kirkwood, within Dunn’s Woods indicated the administration’s priorities about land use. The woods at the heart of the campus, beautiful as they were, could be built on if necessary. Landscape designers such as Ulrich were employed to give ideas about future development. IU did not have the financial resources to implement many of the suggestions immediately, but it was helpful to know the latest thinking of landscape professionals. Ulrich’s concept for the recently acquired Dunn Meadow included an Arboretum with Experimental Garden

and a string of three small lakes fed by Spanker’s Branch, which never went beyond the planning map. Having experience working with local government authorities, he offered to meet with City of Bloomington officials in the hopes of awakening their interest in the improvements, which if completed, at least to a certain extent, could be used as a Public Park [and] be a great adornment to the University & City.

47

Professor Mottier wrote to his old colleague psychologist William Bryan, who had just been named the new president of IU in November 1902, and followed up on some of Ulrich’s recommendations, including his support of a botanical area along the meadow near Seventh Street. Mottier reported that a number of trees,

mostly hard maple, had been transplanted on the campus over the previous few years. These young maple trees together with the older ones will preserve the original character of the primitive forest,

he stated. But he worried about the cost of fulfilling Ulrich’s excellent planting scheme. Instead, Mottier suggested that trees be obtained from the surrounding countryside at little to no cost and that groundskeeper Ogg and his assistants continue to transplant them. Mottier praised Ogg on his diligence: With constant care and vigilance he had kept alive under adverse conditions transplanted trees that with ordinary care would have perished.

48

Another element of stone was added to the campus landscape in 1902—a low wall of limestone along the Third Street south campus boundary. Inspired by a limestone wall of the residence of Joseph Swain, the outgoing president, the trustees arranged to have a similar one constructed.49

After five years of dependable service, in 1904 William Ogg’s title was changed to keeper of the grounds.50 Ogg developed an effective partnership with Mottier to preserve and enhance the campus landscape. The student newspaper wrote about Mottier’s efforts as head of the university’s campus committee to make the grounds the most beautiful in the country.

The article noted that several hundred native trees had been planted over the previous two years.51

Over time, generations of students and faculty interacted with the modest gardener Ogg as he went about his daily work, and he became a beloved figure of the campus community. In addition to planting flowers and trees that brightened the lives of those who took the campus paths,

he was approachable as he performed his duties. Many a one has gone out of his way a little just to have a chat with Mr. Ogg, their friend,

with his steady and accepting demeanor, talking with people in his calm, pleasant and manly way.

52

In 1904, Eugene Dick

Kerr was appointed superintendent of buildings and grounds at the university, following a career as a Bloomington police officer and service as the city’s fire department chief. As the campus expanded, he oversaw all phases of construction and maintenance of the physical plant and became a stalwart adviser to President Bryan and the board of trustees.53

4.4 New Buildings for Science and for Students

Rising enrollments led to the construction of a new building on the eastern line of halls (Wylie and Kirkwood) dedicated to education and research in science. Mitchell Hall, the 1885 frame building, was moved a couple of hundred feet east to make room for Science Hall. In January 1903 during Foundation Day activities, President William Bryan, an experimental psychologist who had just been elected president of the American Psychological Association, delivered his inaugural address and the building’s dedication. The limestone building, with specialized laboratories for research and instruction, was finished in rough-faced ashlar in regular courses. With its many windows and symmetrical design, it presented an austerely modern appearance.54

The Swain presidential administration also planned a women’s building. With the rise of female enrollment to nearly a third of the student body by the turn of the century, President and Mrs. Swain advocated for space to serve the needs of women students: a gymnasium, an auditorium, meeting rooms, and lounges. The planned building was not a candidate for state funding, however, so a student-centered capital campaign was started, and $50,000 was raised, from 2,000 donors. President Swain solicited funds from John D. Rockefeller Jr., who agreed to give an additional $50,000 provided that a wing for male students be included.55

Some writers have rightfully stressed its importance as an intentional space for women students and the role of private philanthropy in funding the building, albeit with a change in conception to serve the entire student body. Fewer have noted its salutary effect on the campus environment. The building became a signature structure not only for its striking design and its red-tiled roof but also for its monolithic clock tower and sonorous chimes. The bells transformed the soundscape of the quadrangle, adding a new element that supplemented the auditory environment emanating from the campus. The typical sounds of the campus—wind whistling through trees, birds singing, the crack of thunder, the patter of rain, students talking, the hush of snowfall, squirrels chattering—was augmented at regular intervals by pealing bells.

The bronze bells, funded by a campaign jointly mounted by the classes of 1899, 1900, 1901, and 1902, numbered eleven, the largest of them four feet in diameter. After installation, the bells were struck every quarter hour, playing the traditional Westminster Quarters

melody, followed by strikes for the number of the hour. In 1906, President Bryan requested that IU’s alma mater be played every day at six o’clock. Bells added something special to the campus experience, as one student from the class of 1909 recalled: I wondered if there really was such a thing as college spirit, and whether it would ever descend on me. Suddenly, the chimes pealed forth in the old college tune. My heart leaped up and as the tone of the last verse died away in the distance, I almost shouted,

56Dear old Indiana!

The Student Building tower harkened back to medieval times when sound was used to mark the hours, and clockfaces were added later for visual reference. The large four-sided Seth Thomas clock, illuminated at night like a full moon, was a boon for students who did not carry pocket watches. And everybody in earshot received a message, often subliminal, about the passage of time—and the reminder that time was passing as well.

As the campus matured, attentive students took notice of its design integrity and natural beauty. In the 1906 Arbutus yearbook, one finds an articulation of IU’s spirit of place by an anonymous student author:

Indiana has the most beautiful campus in the West;these are the words that visitors are so often heard to remark. The great wooded slope, crowned with the six large halls situated in the form of anL,never fails in its first impression. If seen in the summer the foliage is dense, and through it and in contrast with it appear the gray limestone buildings. In winter the view is often more beautiful than that in summer. Just after a heavy fall of snow the ice-laden trees are brilliant in the sunshine. In autumn the grounds are one mass of crimson and yellow leaves from the beeches and maples.This campus which impresses the visitor when he looks upon it, completely wins the heart of the student who spends four years here. Each has his favorite nook to which he likes to retire in spring and autumn. Perhaps the most secluded of these retreats is the little plot of ground know as God’s Acre. It is situated in a clump of trees on the Jordan River. Around the plot runs a stone fence. Inside are a score or so of graves, covered by trailing vines….

Everything about the University has a distinctive appearance. It is

Indiana-like.Once impressed upon the student it does not leave him. What we learn here may pass from our minds, even the images of familiar faces may grow dim, but the Indiana Campus, with its natural scenery, its loved retreats, and its well-remembered trysting places will not be forgotten.57

In two decades of occupancy under four presidents, the campus, using locally sourced materials in a classic design, had developed into a pleasing and harmonious whole.

Alumna author Edith Hennel Ellis, a member of the class of 1911, expressed her appreciation of the campus landscape, especially the many trees. She reiterated the common feeling that its natural charm was the chief asset of the campus

and collectively thanked the individuals who were responsible for preserving that beauty. A sharp observer, she talked about campus design considerations with respect to department faculty who directly shaped planting regimes—and often supplied the physical labor. Ellis singled out botany professor Mottier, who has real genius in landscaping,

for special treatment. He and his colleagues have actually raised and with their own hands transplanted to the campus hundreds of trees necessary in the process of reforestation.

58

Ellis noted that native plants were preferred, but the occasional imports, like the ginkgo trees between Owen Hall and Maxwell Hall, planted in 1896, provided welcome variety. The campus is virtually a catalogue of trees native to this region,

she wrote. One can find beechnuts, hazelnuts, walnuts, chestnuts, hickory nuts, butternuts, haws, locust, black currants, service berries—practically every tree and shrub used by the Indians and early settler for nuts and fruits.

59 She paid homage to groundskeeper Ogg and his associates: The men who have worked with nature to preserve the beauty of the campus may well glory in their work. Like the saints of old, their shadow has blessed all on whom it has fallen.

60

4.5 Enfolding the Woods

In addition to the sundial that was moved in 1896, other souvenirs of the old campus were incorporated into the Dunn’s Woods campus. In 1907, trustee Theodore F. Rose volunteered to pay for a decorative well house to be constructed over the campus cistern between Maxwell Hall and the woods. Equipped with a hand pump and a tin cup, it provided drinking water to the campus community. Previously, the cistern played a role in fighting a major fire in 1900 that destroyed the tower of Wylie Hall. The Daily Student newspaper enthused about the plan: Among all the buildings which will ultimately adorn the University, there will be none so suggestive of sacreder [sic] reminiscences to the old student and so pregnant of possibility for the new as the beautiful new well-house which the trustees will erect on the site of the present cistern pump.

61

Professor of physics Arthur Foley, who consulted on campus building plans and engineering improvements, executed an eclectic design for the Well House, incorporating the 1855 limestone portals from the College Building, the oldest survivor from the early days of the university, still in use as the Bloomington High School.

Although it had a utilitarian use, the Well House harkened back to eighteenth-century English estate garden follies—fanciful structures devised as ornaments to the grounds. The trustees were interested in the plan to reuse the old portals, and Rose offered to pay the entire cost and dedicate it on behalf of the alumni.62 Rose, who graduated in 1875, was a member of an early IU fraternity, Beta Theta Pi, and the footprint of the structure was an elongated octagon, mirroring the shape of the fraternity pin.

Once constructed, the Well House was a magnet for student activities that had little to do with classwork. Placed next to the woods on a main path, it welcomed the entire campus community to slake their thirst. It also served as a social center and meeting place for undergraduates. In 1912, a fictional story—Drinking Fountain at I.U.

—was published in the Indiana Student featuring a first-year coed searching for a drink of water after studying in the library. The water in the library lavatory seemed unpotable, so she went, in turn, to the Student Building, Maxwell Hall, and Kirkwood Hall, to no avail. Spotting men students loafing and smoking around the Well House, she decided not to go there. She found an old water pump near Maxwell Hall, got over her fear of germs, and used a rusty tin cup and quaffed a deep, satisfying draught of the cool, crystal water.

How foolish of me,

she said. It is I who am not up to date. Indiana is following the style of preserving

63old things.

Before long we will have a real, old-fashioned old-oaken-bucket well.

The best-known student tradition associated with the Well House was kissing. Built as an open-air pavilion with a roof, the structure provided a refuge that afforded some privacy on campus and a protected lookout. There is ample evidence that it was soon the site of dates, the exchange of fraternity pins, and, as social mores allowed, hugging and kissing. In a review of campus traditions, student Marvin Shamon noted that first-year students learned about the Well House kissing tradition. Undergraduate women were not considered as true coeds until they kissed at this famous campus shrine for the full twelve strokes of midnight…it has been observed that the chimes of the Student Building clock seem to have a more mellow and full ring to them at midnight than at any other time.

64

In addition to the Well House, another building was being constructed at the same time—a new library. The library, located in Maxwell Hall since 1890, had run out of space, and burgeoning enrollments made this project imperative.65 The university drew up plans for a building twice the size of Maxwell Hall and requested $250,000 from the state legislature for construction costs. The legislature appropriated $100,000. Librarian William Jenkins made a fact-finding tour of the best libraries in the country and consulted with President Bryan to plan a building to which additions could be made over time. Patton and Miller, a Chicago architecture firm that had built more than one hundred Carnegie community libraries, oversaw construction.

Located west of the Student Building, on the corner of Indiana and Kirkwood Avenues, near the main entrance to campus, the library completed the north row of buildings framing the quadrangle. The sizable reading room presented design challenges:

Construction of the University Library was delayed when the contractor and then also the architects stated that they did not know how to make the ceiling of the large reading room of one concrete slab in such a manner that the structure would be safe. A Chicago engineer called in consultation was likewise unable to give satisfactory advice. We then asked three of our professors—Lyons (Chemistry), Foley (Physics), Miller (Analytic Mechanics)—to consider the problem. They made the necessary chemical and mathematical studies and submitted plans and specifications for a safe construction. These were adopted and building proceeded accordingly.66

When the building was completed in December 1907, the books were moved during winter break. In March 1908, President Bryan noted approvingly that the use of the library had jumped at least 25 percent. He boasted that the 200-seat reading room had been filled to capacity already, and the great reading room is the lightest and quietest reading room of the size I know of and compares favorably in attractiveness of any similar room in the country.

67

The University Library was the biggest building on campus, and its distinctive English Gothic style mixed with Jacobean features in native limestone supplied an anchoring presence. Its red-tiled roof provided visual continuity to the neighboring Student Building. The university seal was carved high in the south-facing gable, announcing the motto Lux et Veritas—light and truth—to all who pass.

68

In 1909, another science building, dedicated to biology, was among the priorities of the university’s budget request to the state legislature. The general assembly granted $80,000, about a third of the amount requested. A decision was made to place the building near Third Street, southwest of Science Hall, to start another side of the frame of buildings enclosing Dunn’s Woods. The primary entrance faced the woods to the north; the south entrance was on Third Street. This would be the eighth academic hall constructed in the quadrangle since the campus was opened a century earlier. Robert Frost Daggett was the architect. With simple but effective symmetry in collegiate Gothic design executed in limestone, the building was the first on the south campus boundary. A faculty space committee decided that the Department of Botany would occupy the first floor and the Department of Zoology the third floor, with the Department of English on the second. Because of a continuing campus space shortage, Biology Hall was populated in the middle of the 1910 fall semester.69

In April 1910, a 200-year-old tree was destroyed to make way for the heating plant tunnel, and the editor of the Indiana Daily Student was incensed. None of the natural growth of trees,

he fulminated, are less than 125 years old. Storms and decay are destroying the magnificent trees at a rate of six a year.

70 Apparently, student reporters were not aware of the continuing efforts of Ogg and Mottier to replant native trees.

4.6 University Lake

When the campus moved from Seminary Square to Dunn’s Woods, cisterns and wells supplied water, but as the institution grew, it came to depend on Bloomington’s water utility. The city was between two forks of the White River rather than on a lake or river. Beginning in the mid-1890s, a series of dams was created to form artificial lakes on the town’s southwestern outskirts. But the limestone bedrock was full of sinkholes and underground streams, so the lakes were leaky, and the water plants proved inadequate.71 By the 1903–04 academic year, the trustees were in meetings with the city administration, and they decided to have two additional wells dug on campus. By 1908, the situation had escalated. What had long been an inconvenience and annoyance now had become a great menace,

wrote Burton Myers, dean of IU Bloomington School of Medicine, as the administration began to take steps to provide the university with its own independent water supply.72

In 1909, the Indiana legislature appropriated $20,000 for a university water supply. IU geology professors advised looking at the northeastern outskirts of Bloomington, where limestone karst gave way to sandstone formations that were less permeable. Test wells were dug in the Griffy Creek valley, but they proved inadequate, so a narrow gorge farther up the valley was dammed. Additional funds were appropriated in the following years to raise the height of the dam and to purchase the 250 acres of land surrounding the impoundment.73

After the dam was completed in 1914, a coal-powered waterworks plant was built, and pipes were laid to campus a mile away. The sixteen-acre reservoir, dubbed University Lake, supplied the needs of IU’s physical plant, but water shortages still affected students and staff because their residences were served by the inadequate Bloomington water utility. Governor Samuel Ralston grew irritated at the city’s failure and threatened removal of the university: The water situation in Bloomington is very serious. I have about made up my mind as Governor to ask the legislature to take account of the situation and, if necessary, to remove the University from its present site.

74

Public opinion was galvanized, and the Bloomington water utility constructed a reservoir downstream of University Lake, damming the main channel of Griffy Creek. The resulting Lake Griffy was completed in the mid-1920s and solved the community’s chronic water shortage.75 For a time, University Lake was popular among students as a hiking destination and for picnics.76 Although it was institutional property and it served the university infrastructure, it was not considered part of the campus proper.

4.7 Three Decades in the Woods

In November 1913, botanist David Mottier teamed with Ulysses Hanna, a mathematics professor, to submit a report to the IU Board of Trustees, Suggestions on the Improvement of the East Campus.

Referring to a twenty-one-acre plot east of the quadrangle purchased a few months before, the faculty members’ recommendation was for a forest landscape like the original University Quadrangle. They envisioned a second quadrangle of buildings, a garden, and an athletic field, with the possibility of a small lake from the damming of a tributary of Spanker’s Branch.77 No action was taken on the report, and the purchase of another twenty-six acres in the vicinity the next year prompted a search for a landscape architect.

With rising enrollment as well as the growing popularity of college athletics, campus sentiment was in favor of a new gymnasium. The existing gym, built in 1896, was already too small. A wooden structure, it was located awkwardly east of Owen Hall, right outside of the quadrangle.

In December 1914, the trustees prepared a report to the governor and the visiting committee about this urgent priority. Reflecting conventional wisdom about the foundational role of physical education, the report stated, It is needed by all the men of the University; not only by those who take part in athletics, but still more by the hundreds and thousands who do not take part in athletics.

78 In addition to a new gymnasium, several other construction needs were mentioned, including an education building, an administration building, an auditorium, a library addition, and a dormitory for women.79 It would take the next quarter century to accomplish these building projects.

By 1915, the Bryan administration had successfully established the School of Medicine, with its program split between Bloomington and Indianapolis, and dealt with steadily rising enrollments. A fine physical plant had developed over thirty years. It boasted eight substantial academic halls, plus a gymnasium, an observatory, and a well house, arranged in an expansive quadrangle with Dunn’s Woods at the center. The aspirational label University Park

faded quickly, but the conservationist ethos did not. It aligned with the repeated financial exigencies presented by meager state funding as well as the pioneer make do

attitude. There were still building sites on the great quadrangle that framed Dunn’s Woods, plus more undeveloped land, on the 118-acre campus.

Kate M. Hight, “Reminiscences,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 24, no. 4 (1937): 455–60, quote on 455.↩︎

Carrol Krause, Showers Brothers Furniture Company: The Shared Fortunes of a Family, a City, and a University (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012).↩︎

David Schuyler, “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Origins of Modern Campus Design,” Planning for Higher Education 25, no. 2 (1996–1997): 1–10, quote on p. 10.↩︎

Clarence L. Goodwin, “The Indiana Student and Student Life in the Early Eighties,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 17, no. 1 (1930): 155.↩︎

Brother Robert was an Indiana politician and statesman, and brother David was a well-known American geologist.↩︎

Student, February 1886, cited in Thomas D. Clark, Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume I: The Early Years (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970), 228.↩︎

Bloomington Telephone 7, no. 46 (March 29, 1884): 1; See also Frank K. Edmondson, “Daniel Kirkwood—‘Dean of American Astronomers’,” Mercury 29, no. 3 (2000): 27–33, quote on p. 32, who mistakenly dated it as 1885.↩︎

Bloomington Saturday Courier cited in Clark, Indiana University, 1970, 228.↩︎

Naturally, the trustees were concerned with maintaining and protecting the new physical plant. In 1885, they hired John W. Stuart as the janitor of the new campus to be responsible for the heating and lighting systems of the three new university buildings as well as general upkeep. His caretaking extended to campus grounds surrounding the new buildings. He was required to give

his entire attention and time including vacations

to the job. Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 June 1885–10 June 1885” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 10, 1885), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1885-06-03.↩︎Clark, Indiana University, 1970, 228; J. Terry Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington: America’s Legacy Campus (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 46–47.↩︎

See bio of Olof Benson.↩︎

The report is in the IU Archives, but the sketch has disappeared. Hearsay located it on an office wall in Maxwell Hall as late as 1916.↩︎

“Description of the Plan of Improvement of University Park” (Indiana University Archives/C77/B1, 1884).↩︎

“Ideas Concerning Campus Plans Change Considerably with Time,” Indiana Daily Student 41, no. 98 (February 11, 1916): 3.↩︎

A Hoosier Holiday (New York: John Lane Company, 1916), 489. The stile was probably located at Fourth Street and Indiana Avenue.↩︎

Both David H. Maxwell and son James Darwin Maxwell were IU trustees in the nineteenth century. For the naming of Maxwell Hall, see Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 20 March 1894–23 March 1894” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 22, 1894), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1894-03-20.↩︎

Tom Roznowski, “The Trees Grew First: IU’s Woodland Campus,” The Ryder, April 2017, 24–25.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 11 June 1891–17 June 1891” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 16, 1891), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1891-06-11. By 1898, the budget for Stuart and staff was $2,000. For comparison, the president, Joseph Swain, was receiving $5,000 and full professors’ salaries ranged between $2,000 and $2,500; see Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 November 1898–18 November 1898” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 18, 1898), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1898-11-16.↩︎

James A. Woodburn, History of Indiana University: Volume I, 1820–1902 (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1940), 431–32.↩︎

Much later enshrined as the Old Crescent, after 1980. See Chapter 6.↩︎

Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington, 324; “‘Local’ Column,” Indiana Student, May 26, 1896, 29.↩︎

Edith Hennel Ellis, “The Trees on the I.U. Campus,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 16, no. 3 (1929): 328–31.↩︎

Indiana Student, April 6, 1901, 12. A

spring case

refers to a springtime infatuation.↩︎“The Decline of Campustry,” Daily Student, November 11, 1903.↩︎

David Mottier to President Bryan in 1911, reported in Thomas D. Clark, Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume II: In Mid-Passage, 4 vols. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973), p. 14.↩︎

David Mottier, “Letter to Joseph Pierce” (Indiana University Archives C174/B31/F Mottier, David, February 13, 1896).↩︎

For a history of the firm, see Olmsted Firm.↩︎

Olmsted Olmsted and Eliot, “Letter to Joseph Swain” (Indiana University Archives C174/B32/F Olmsted, Olmsted,; Eliot—Campus Plan 1896, December 8, 1896).↩︎

The bur oak, located at the north entrance to the Indiana Memorial Union commons, is still alive; the beech tree was removed when the Tudor Room was built in 1957.↩︎

Burton Dorr Myers, History of Indiana University: Volume II, 1902–1937, The Bryan Administration, ed. Burton D. Myers and Ivy L. Chamness (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1952), 755.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 November 1897–06 November 1897” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 5, 1897), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1897-11-04.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 23 March 1899–25 March 18997” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 25, 1899), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1899-03-23.↩︎

Robert Ogg served as a trustee from 1896 to 1902. When Ogg’s brother Robert died in 1936, President Bryan remembered the brothers:

Robert A. Ogg and William R. Ogg—they were brothers on a farm more than eighty years ago. It was decided within the family that one of the brothers could go to college. Many a time, often through storms and over roads when the mud was bottomless, the brother who was to stay on the farm brought to Bloomington the brother who was to have the great prize of a college education. Graduation day of 1872 came bringing glory to Robert and unselfish happiness to William and to all of the family.

Bryan quoted in “In Memoriam: William A. Rawles, ’84, Robert A. Ogg, ’72, William T. Patten, ’93; and Necrology List,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 23, no. 3 (1936): 303–13, pp. 309–310.↩︎“Football Men Wore Mustaches When He Came to University,” Indiana Daily Student 50, no. 56 (December 3, 1921): 2.↩︎

Ulrich (1840–1906), a German-born landscape architect, worked with Frederick Law Olmsted laying out the grounds of Chicago’s 1893 World Columbian Exposition. Rudolph Ulrich, “Letter to Joseph Swain” (Indiana University Archives C174/B44, May 1899).↩︎

See

R. Ulrich plan of campus with proposed locations of future buildings, walkways, etc.

The current names are: Student = Frances Morgan Swain Student Building; Science = Ernest H. Lindley Hall; Biology = Joseph Swain Hall East; and Commerce and Finance = William A. Rawles Hall.↩︎See

R. Ulrich plan of campus with proposed locations of future buildings, walkways, etc.

↩︎David Mottier, “Letter to William Bryan” (Indiana University Archives C174/B31/F Mottier, David, November 5, 1902).↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 24 March 1902–25 March 1902” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 25, 1902), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1902-03-24; Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 September 1902–15 September 1902” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 6, 1902), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1902-09-03.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 June 1904–22 June 1904” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 22, 1904), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1904-06-16.↩︎

“Campus Improvements Due to Prof. Mottier,” Indiana Daily Student, February 5, 1904, 1.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 01 October 1948–02 October 1948” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, October 1, 1948), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1948-10-01.↩︎

No man within my knowledge has given a more honest, skillful, successful and devoted service to Indiana University than Eugene Kerr. He knew what to do. He knew how. He knew how to make men work hard and like the work and like him. He was every inch a man,

William Lowe Bryan’s tribute to Kerr at his death.↩︎Myers, History of Indiana University, 38–44; Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington, 42–45.↩︎

“Well-House Innovation,” Daily Student, October 15, 1907, 1, 6.↩︎

Mrs. Rose was the granddaughter of President Andrew Wylie. Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 19 June 1908–23 June 1908” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 22, 1908), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1908-06-19.↩︎

“Drinking Fountain at I.U.” Indiana Daily Student, March 9, 1912. The football tradition to award the

Old Oaken Bucket

to the winner of the IU vs. Purdue game was begun in 1925.↩︎Marvin Shamon, “The Traditions of Indiana University” (Indiana University Archives/Reference file: Buildings—Bloomington Campus Well House, Rose., c1935?).↩︎

From 1884–85, when attendance was 157, to twenty-five years later, in 1909–10, when 2,562 students were in attendance. Myers, History of Indiana University, p. 85.↩︎

Robert E. Lyons, Arthur L. Foley, John A. Miller. Myers, pp. 34–35.↩︎

Myers, History of Indiana University, 149–53; Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington, 58–61.↩︎

Much later, Thomas Clark took issue with that estimate, stating that Mottier and Ogg had been planting native trees from the university’s nursery for the last decade.

This gave the appearance that the trees had sprouted from seed where they stood,

(Indiana University, 1973), p. 14.↩︎Stephen S. Visher, “Water Supply Problems of Bloomington, Indiana,” Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 66 (1956): 188–91.↩︎

For a description of the dam, see E. R. Cumings, “The Geological Conditions of Municipal Water Supply in the Driftless Area of Southern Indiana,” Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 21 (1911): 124–29, https://journals.indianapolis.iu.edu/index.php/ias/article/view/14025.↩︎

David Mottier and Ulysses S. Hanna, “Suggestions on the Improvement of the East Campus” (Indiana University Archives C174/B31/F Mottier, David, November 10, 1913). report to IU Board of Trustees.↩︎