7 Landscapes of Learning

We know that the campus itself must be the teacher, a place that gives vitality, meaning, and memory to the learning experience, not just within the confines of the institution but in the times and places beyond. I have argued that those are the fundamental attributes of the place-based institution—its soul, if you please—that have enabled it to persevere throughout our restless history, to continuously transform itself as it has tackled the ever-changing needs of American society.

—M. Perry Chapman, American Places: In Search of the Twenty-First Century Campus

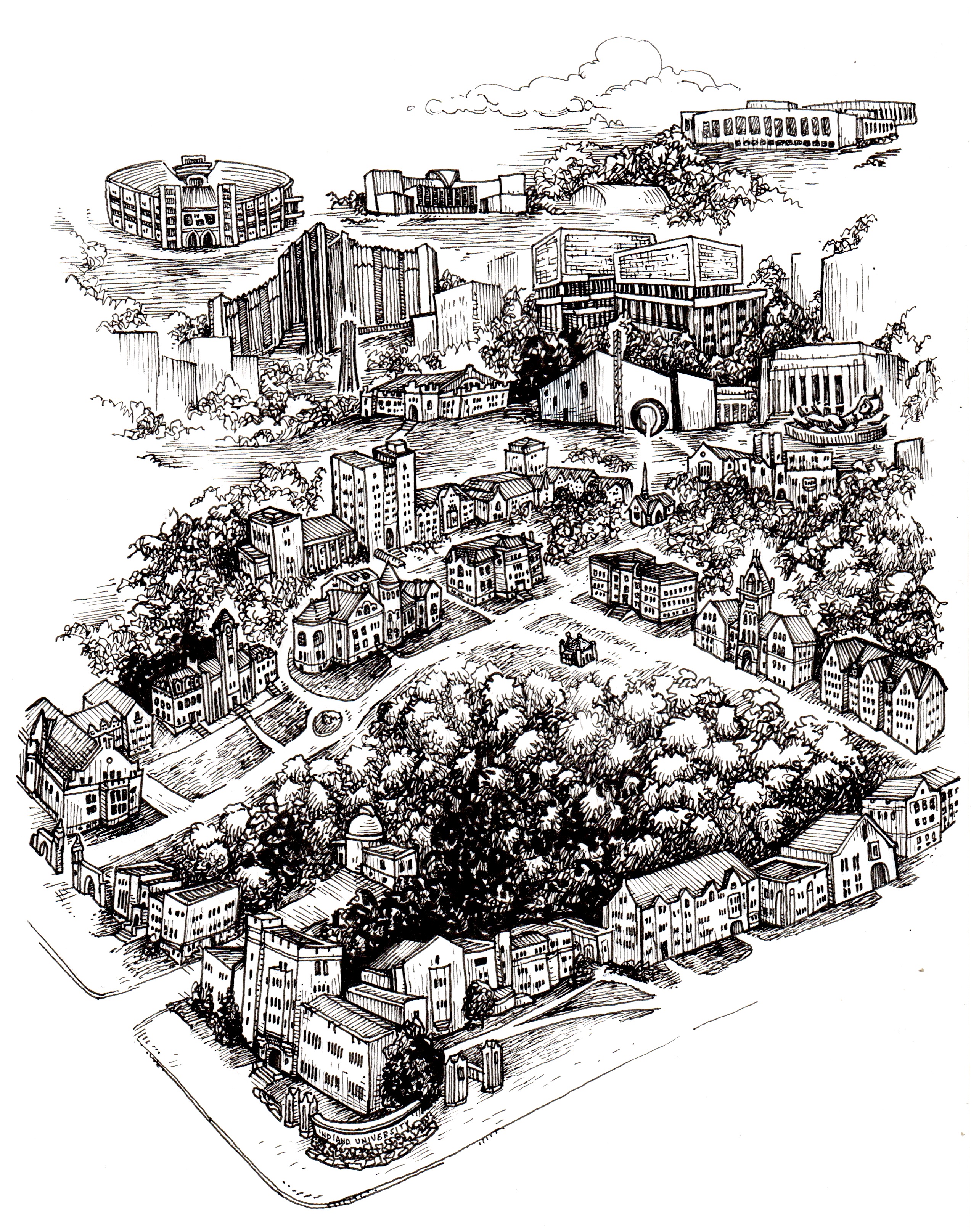

The flagship Indiana University campus one sees today is but the latest culmination of a partnership between humans and nonhuman nature that began in 1885. The environmental history of the IU Bloomington (IUB) campus between 1980 and 2020 was shaped by a shared understanding of the importance of the woodland theme in campus design that emerged in the 1880s and its successful adaptation to post–World War II circumstances. Presidents John Ryan (1971–87), Tom Ehrlich (1987–94), Myles Brand (1994–2002), Adam Herbert (2003–07), and Michael McRobbie (2007–21) continued this remarkable continuity of vision and practice while their administrations served as stewards of the campus design ethos. But leadership was only one part of the equation. Faculty, staff, students, alumni, and Bloomington townspeople shaped the campus with their actions and care, as did architects, contractors, and gardeners who brought plans and blueprints to life.

Relabeling the Dunn’s Woods quadrangle of buildings as the Old Crescent in 1980 served to differentiate the historic core from newer areas on the sprawling campus. But the challenges to integrating academics, residential life, and athletics within the physical plant continued. Construction persisted, with a mix of new buildings, renovations of older structures, and, occasionally, wholesale redevelopment. In this period, university officials occasionally faced organized local public opposition to proposed land use decisions and facility planning, sometimes leading to the modification or abandonment of design schemes.

7.1 Law School Addition

The School of Law building, located at Indiana Avenue and Third Street since 1957, anchored the southwest corner of the historic campus quadrangle. Concern over maintaining accreditation standards led to plans to expand and renovate the law library, and the Ryan administration negotiated with the Phi Gamma Delta (Fijis) fraternity next door to buy their property. After talks collapsed in the fall of 1981, the board of trustees approved the construction of an addition on the back of the existing law building.1 Soon after, Professor David Parkhurst, in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs, noticed the survey stakes encroaching into Dunn’s Woods and raised concern, writing in mid-January 1982 to Bloomington Chancellor Ken Gros Louis as well as the Indiana Daily Student.2

The IDS broke the story about the plan for the 57,000-square-foot addition, which would require the removal of twenty-two trees. Parkhurst stated, I want nothing less than total preservation of the woods, so I object to this very strongly. I thought those woods were sacrosanct.

University Physical Facilities Director Terry Clapacs said that steps would be taken to minimize impact on the woods. When Parkhurst charged that the plan lacked public discussion, Clapacs and assistant dean of the law school Arthur Lotz disagreed: We talked to central administration, President Ryan, Chancellor Wells, the vice presidents, Board of Trustees and the Higher Education Committee [sic].

The article reported that drawings posted in the law school lobby showed a cleared area three times the size of the addition, but Clapacs maintained that only the perimeter of the building was finalized.3

Public debate was thus begun. The Department of Astronomy, incensed that they were not consulted, complained that the addition would ruin the [Kirkwood] observatory.

4 On February 1, law school dean Sheldon Plager, a former environmental attorney, circulated a memo, The Woods and the Law School Library Addition,

attempting to address concerns about the brewing controversy. Taking a balanced tone, he expressed concern for the woods but also the academic programs. He went through the failed negotiation with the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity to purchase the adjoining property and the lengthy design review, which involved seven alternative plans. From the beginning of the planning, the law school wanted to take advantage of its proximity to the woods and reorient the backside of the building. Plager minimized the concerns about the Kirkwood Observatory expressed by the astronomy department.5

A couple of days later, a public meeting was held in computer science professor Douglas Hofstadter’s Lindley Hall office to organize a group to stop this ugly threat

to the woods. Called Save the Woods,

the group circulated an open letter, citing the one-hundred-year history of Dunn’s Woods, noting that it had been placed on the National Register of Historic Places just a year before. If you resent the expedient disregard of the Trustees and the present I.U. officers for one of I.U.’s biggest drawing cards and the surest symbol of the University’s traditions, you should be heard

—the open letter urged individuals to write to the trustees and the president.6 Save the Woods announced a plan to sponsor a ribbon-tying ceremony that Friday, where they will tie green ribbons around trees earmarked for removal, and, if enough ribbon is available, also around the observatory.

7 Meanwhile, in that same week, the student Environmental Law Society hosted a forum in the law school about the addition. Faculty member Craig Bradley announced that the plans would be resubmitted to keep it outside the Old Crescent boundary.8

Save the Woods started a petition to the IU trustees, and soon over two thousand signatures had been gathered, as well as several organizational endorsements.9 Parkhurst reached out to a visiting professor of music, Leonard Bernstein, in early February, hoping to garner support from the famous composer. Bernstein’s note was published in the IDS: I should like to go on record as opposing strongly the violation of the so-called Old Crescent woods in favor of extended building facilities. In my short stay here I have been deeply impressed by the care taken to preserve the natural beauties of the campus, and it would be sad indeed to see this long-standing tradition broken.

10

In mid-February, IDS student columnist Dan Brogan admitted confusion: How do you justify something for one academic unit that will harm so many other aspects of the campus and community?

He added, Compromise would seem to be the answer.

Brogan wondered why law school officials seem oblivious to any needs but their own.

11

President Ryan met with law school officials and supporters, as well as people who opposed the plans. He explicitly stated he would seek alternatives and oppose removal of trees

from the Old Crescent. To prevent future problems, Ryan supported developing a clear policy for the woods and other natural areas on campus.12

The Environmental Law Society weighed in and released a statement. The students were opposed because university officials have failed to consider both state environmental policies and the views of those persons affected by the proposed addition.

The group found no evidence of an environmental assessment as plans were developed and noted the failure to share information with the academic community and the public. They supported the expansion of the law school but not at the cost of the natural and historic environment.

13

Before the trustees’ meeting in early March, letters to the editor of Bloomington’s Herald-Telephone proliferated. One was penned by law professor emeritus Ralph Fuchs, who recalled a magnificent beech tree standing where the Tudor Room in the Memorial Union was then located. He cautioned against one-sided policies that either favored institutional needs or focused on the natural environment exclusively. In respect to the law school addition, the question is whether the educational needs of the school prevail over the preservation of the particular trees involved. The value of the trees depends upon their location and quality, their role in the surrounding ecology, and any applicable considerations of law or stated public policy,

Fuchs summarized. About the beech tree that was sacrificed to make way for the union’s expansion in 1958: no one raised objections, yet many doubtless mourned its loss, as I still do.

14

On March 6, opponents of the addition had their first chance to air their views directly to the board of trustees at meetings of their architectural, faculty relations, and student affairs committees. Addressing the architectural committee, Professor Hofstadter said that on his first visit to the Bloomington campus in 1967, he was particularly struck by the beauty of the woods

and urged the trustees to affirm it as a protected entity.

Professor of Astronomy Martin Burkhead asserted that heat and light from the addition would make Kirkwood Observatory useless.

At the faculty relations committee, Professor and Chair of Astronomy Hollis Johnson noted that the observatory had recently been renovated to accommodate a new solar telescope, making it one of the best telescope facilities in the Midwest.

At the student affairs committee meeting, senior Mark Kruzan, President of the IU Student Association, read a unanimous association resolution in opposition to any plan that infringes on the wooded area.

15

Responding to the public outcry, the trustees took another look at the plan after their March meeting. Privately, trustee Harry Gonso, an Indianapolis attorney, complained to the other members of the board about the misinformation that had been spread across the state, such as rumors that the entire forest would be removed and the Rose Well House razed. President Ryan commiserated and reminded the board that all plans must spare any intrusion into the woods.16

In its reporting, the Herald-Telephone attempted to quell some of the rumors, such as bulldozers would down trees in the Old Crescent and that the Well House would be torn down.17 Although glad that Ryan asked for other options to be explored, the IDS Opinion Board was skeptical about officials’ concern about minimizing impact on Dunn’s Woods. They applauded the efforts of Save the Woods: Had the group never been formed, the University may have forged ahead with the plan and actually broken ground.

18

The architects went back to the drawing board and submitted a revised plan within a month. The new plan was farther away from the observatory and pulled back the twenty-four-feet intrusion into Dunn’s Woods. Among the design changes were blinds on the windows facing the observatory and white marble chips on the roof to limit possible image distortion. The board of trustees approved the changed plan on April 2.19 Relieved that the law school needs would still be met, Dean Plager quipped: It gets us out of the woods—literally and figuratively.

Some astronomers remained skeptical, however. The Save the Woods group would be disbanded shortly, their mission accomplished.20 After a few days, the IDS Opinion Board editorial headline read: How the Trees Were Saved, Law Addition Flap Is Finally Over.

21

Board of Trustees President Richard Stoner issued a form letter to all who wrote to the board, seeking to smooth ruffled feathers: I regret the misunderstandings generated by the original announcement. Please rest assured that the Trustees, all alumni, share your deep concerns for the landmarks and traditions of our University.

Stoner, in practicing damage control, concluded that it was heartwarming to me to see so many loyal alumni

22rise to the cause

when they felt something might happen to change the campus they love.

President Ryan also sent personal notes to the main participants, including Professor Parkhurst, thanking him for expressing your thoughts, and for your loyalty.

23 The board of trustees requested that the University Heritage Committee recommend policy regarding definition of areas, as well as factors to consider in determining their protection and use.

24

In the light of history, this episode revealed the emergence of a new force to affect campus planning: a coalition of interested local citizens, many who had ties to the university. The ad hoc group sprung up in response to a threat to natural areas on campus, demonstrating the wide concern about environmental and historic values that was shared among students, faculty, staff, alumni, and townspeople. Tending to buildings and landscapes on campus was within the proper purview of the IU administration, but public sentiment provided needed checks and balances in a university whose aim was to serve the public.

7.2 University Woods

near Griffy

The University Heritage Committee, chaired by Chancellor Wells, held a hearing on campus green areas on April 29, 1982. Among the sites mentioned were Dunn’s Woods, the grove between Myers Hall and the Chemistry Building, the old stadium area, East Seventh Street between Jordan and Union, the Bryan House area, and University Woods near Griffy Lake. A separate committee, the Natural Areas Committee, concerned with teaching and research, was remobilized to provide input to the Heritage Committee.25 Wells said that the university can’t cut off future development of the campus, but it can try to anticipate problems.

26

John Ross, professor of recreation and park administration, wrote to Chancellor Wells about the green areas on campus, suggesting that campus walkways be enhanced by small gathering places to watch one another, to engage in conversation with friend and faculty, to dream a little, to argue and debate, and to perceive life and the surroundings.

He suggested endorsing his colleague James Peterson’s proposal for a blue ribbon planning effort

in the University Woods–Griffy green area. The Griffy site is said to be the largest

Ross said that the idea had been around since before 1960 and had been analyzed by planning classes.27natural area

in close proximity to central city of any city of this size in the country. The proposal for a nature center

is further enhanced by potential users from nearby Meadowood.

7.3 A Stadium of Green

President Ryan, newly sensitized to issues concerning the natural areas of campus, agreed with a plan suggested by Bloomington Chancellor Gros Louis about what to do with the site of the Tenth Street Stadium (the former Memorial Stadium), built in 1925. IU football moved in 1960 to the new Memorial Stadium, in the athletics complex on Seventeenth Street. The Little 500 men’s cycling race had been held at the old stadium since the beginning of competition in 1951, and the old stadium provided a major site of filmmaking for the feature film Breaking Away, released in 1979. After more than fifty years of service, the old stadium was deteriorating beyond repair, and it was to be razed in 1982.28

Located due west of the library building, the seven-acre site was close to several academic buildings lining Tenth Street, so supplemental parking became a popular suggestion. Others thought the space should be reserved for future buildings. Instead, Ryan, with the aid of Gros Louis, hatched a plan to convert the area back into green space. Doing so would provide several benefits to this campus precinct: visual relief from the streetscape, a striking backdrop to the massive bulk of the Main Library (now Wells Library), and a pleasant place to walk or wander. Their idea was to symbolically give

the embryonic arboretum as a gift from the president to the graduating class, thus short-circuiting lobbying efforts from interested parties for alternate uses. Gros Louis, a fine wordsmith, hit upon an apt phrase: a stadium of green.

The two men rewrote Ryan’s commencement speech, weaving in descriptions of the trees, flowers, colors, and scents that would grace the emerging stadium of green.

29

At commencement, President Ryan unveiled the plans to create and nurture a place of woodland beauty—a Hoosier Arboretum

on the site of the old stadium. With plantings of trees and shrubs from Indiana and every other state, as well as specimens from around the globe, he continued, Just as you have come here from throughout the world, so let this new

30stadium,

a stadium of green and growing things, represent you in its diversity. Let it represent you in the Class of ’82 in the seasons which stretch out before you, grow in character, in splendor of achievement, in grace and presence; so also the Arboretum will grow in scope and breadth.

Steeped in the culture of the Bloomington campus, Ryan and Gros Louis conceptualized a striking redevelopment of a significant area of campus, recognizing the opportunity to de-urbanize several acres. As the center of campus moved northeastward, toward Tenth Street and Jordan Avenue, an arboretum would connect the main library and Woodlawn Field, providing an unbroken green expanse along several blocks of Tenth Street.

As demolition of the stadium proceeded, several structures were preserved, including ticket booths, flagpoles, and the wrought-iron fence along the west perimeter. Soil was brought in and sculpted into gentle hills, and a small pond was excavated in the center.31 Reviewing the arboretum through a historical lens, landscape historian Anita Bracalente suggested that it represented a delayed fulfillment of the 1896 Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot plan.32

7.4 Courtyards, Gates, and Campus Appreciation

In October 1985, a century after the university relocated to Dunn’s Woods, Owen and Wylie Halls were rededicated in a ceremony that included both a tree planting and the conferral of an honorary Doctor of Laws degree on David S. Broder, the distinguished journalist. The Student Building bells played Hoagy Carmichael’s Chimes of Indiana

as President Ryan presided over the occasion. A Tree Planting Litany

was organized as a call-and-response exercise, with representatives from the university community:

Faculty & Administration Representative:

Trees symbolize growth and continuity.

Audience:Even as the light of the sun nurtures these trees, the light of knowledge nurtures our minds.Student Representative:

They are sentinels that have grown with the University since Owen and Wylie halls were built.

Audience:Even as their leaves fall, they remind us of the seasons of our lives.Faculty & Administration Representative:

We plant these trees to remember the founders of this University and the creative leaders who came after them.

Audience:As they grow, may they bring added beauty to the campus and enrich the lives of those who frequent this place.Alumni Representative:

We plant these trees for those who will follow us and to commemorate this centennial occasion, committing ourselves anew to the mission of Indiana University.

Audience:Even as they mature, may we grow in understanding and deepen our commitment.33

Nearing the close of his administration in 1987, President Ryan pursued a pet project: a verbal depiction of the design of the Bloomington campus, organized around the trope of courtyards. The template harkened to the English medieval tradition found at Oxford and Cambridge universities in which four buildings, constructed at right angles to each other, enclosed a common lawn or green space. Juliet Frey, the president’s speech writer and editor, composed a first draft of twenty-five pages, started a list of quotations, and assembled a bibliography. Ryan edited the draft extensively, rewriting the prose and reorganizing the text, and crafted a lyrical homage to his beloved campus called Islands of Green and Serenity: The Courtyards of Indiana University. Illustrated by beautiful paintings and inspiring quotations, the main thrust of the narrative was to illuminate how the campus was designed so that everywhere the eye rests, it should see something of beauty.

Meditative and uplifting, this publication focused on the campus as a cultural landscape that constituted a work of art.34

For decades, university administrators aspired to install ceremonial gates at the main campus entrance at Kirkwood and Indiana Avenues, and the university archives accumulated numerous unbuilt plans. In 1987, this long-held vision was realized through a gift from IU financial aid director Edson Sample, made in honor of his parents. Constructed of limestone, the Gothic-style gateway features twin towers connected by short walls with open arches. At the dedication in June, President Ryan mused that the campus grounds were hallowed by an echo of the footsteps of thousands of members of the Indiana University community who came here throughout 102 years, in their search for greater knowledge and understanding.

35 Vice President and Bloomington Chancellor Ken Gros Louis spoke of the gates as entrances, to the university looking east as well as to the greater world looking west. The Sample Gates,

he continued, both into the campus and from the campus into the community, hopefully, ideally, and I believe realistically, are not two paths, but one, with access, vision, understanding, ideas going easily and equally in both directions.

36 Afterward, the gates blended so well with the historic precinct that they became iconic, framing the Student Building bell tower in countless photographs.

In 1991, an outside authority affirmed what IU aficionados long believed: the Bloomington campus design was exceptional. Landscape architect Thomas Gaines published The Campus as a Work of Art, a comparative study of American campuses. Pressing the claim that the physical college campus in its totality was a legitimate art form, the book attempted to define aesthetic criteria of the ideal campus and analyzed two hundred examples from the United States. The narrative featured comments on the IU campus as well as quotes from longtime university architect Raymond Casati.37

As the IU campus grew, university president after university president refused to cave into the pressures for routine development and determinedly preserved its campus in the woods,

Gaines noted approvingly.38 Education is an endeavor that is most sensitive to ambience; students respond all their lives to memories of the place that nourished their intellectual growth,

suggested Gaines, citing empirical evidence that a campus’s visual environment is an important factor in college choice. IU architect Casati pointed out that design standards set by the IU campus could set the bar when students encounter other environments: In other words, you won’t settle for anything less than you’ve had here.

39

Gaines commented on the interaction between collegiate Gothic architecture and natural landscaping. The campus was visually coherent, with limestone providing the dominant building material. Any minor variations in the overall architectural pattern, ranging from Romanesque to Art Deco, provided pleasant accents. That meant that unusual buildings, a few built by starchitects,

could be fit into the campus fabric to provide contrast and excitement. Gaines cited two examples. The main library, opened in 1969, was a strong cubistic statement of stone,

designed by the Eggers & Higgins firm and dubbed The Towers of Silence.

It was placed near the residential zone rather than at the center of the classroom area, which was out of the ordinary, and its long approach relieves the enormity of the building,

he explained, thus avoiding an otherwise overbearing presence.

40 Despite some controversy over a modern building set within the traditional collegiate Gothic environs, Gaines appreciated how the concrete and glass I. M. Pei art museum (since renamed the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art) fitted into the Beaux Arts–inspired Fine Arts Plaza in 1982, noting its scale, siting, materials, and design excellence do no harm to the fine aesthetic tradition of the campus.

41

In his summary, Gaines noted that Indiana never lost that sense of being a university in the woods,

understanding that it was a matter of aggressive cultivation

of the woodland leitmotif. He singled out the lengthy career of groundskeeper William Ogg and his ongoing efforts to replace campus trees by transplanting trees obtained from surrounding forests. Medieval masterpieces such as turreted Maxwell Hall and rusticated Kirkwood

adorn the still-intact Old Crescent, and the campus added interesting and related urban spaces

as it grew, staying true to its design goals. He mentions the Union, the buildings and fountain that make up the Fine Arts Plaza, and the art museum. Walking past the huge and characterless classroom building Ballantine Hall

to another forested area, he quipped, Little Red Riding Hood would have felt at home on this campus.

Gaines concluded,

Indiana University is exciting. You never know what is coming up next. You must walk through hilly gardens and woods to get to classes, to dorms, to the library, to the union. Surprise is surely a worthy goal of design. It is more difficult, I believe, to develop an interestingly cohesive campus without the traditional axes or quads on which planners hang their hats. And it is more dangerous to try. Indiana succeeds, because its visual quality is largely based on the unexpected.42

The IU campus was listed as number five on Gaines’s list of the top fifty campuses, within the top-ranked group of thirteen. The campuses were rated on four criteria: urban space, architectural quality, landscape, and overall appeal.43

A year after the Gaines study was published, the IU arts and sciences alumni publication, The College, featured an article about the design history of the Bloomington campus. Dottie Collins, the research associate for Chancellor Wells, spoke about a mulberry tree growing close to the front entrance to Owen Hall, where Wells’s office was. It produced abundant sweet fruit, much of it ending up on the sidewalk and stairs and then getting tracked inside. Wells resisted repeated calls to cut the tree down and instead had his assistants gather mulberries for his consumption. The article cited Wells as a campus guardian: Sixty-one [sic] years after he arrived on campus as an undergraduate, he remains the living link with its woodland beginnings.

He was taught respect for the woodland campus by the likes of President Bryan and groundskeepers William Ogg and Milburn Beck.44 After he became president in 1938, he has been teaching the lessons of preservation to his successors

with the aid of advisers such as landscape consultant Frits Loonsten.45

Charles Hagen, professor of plant sciences, was interviewed. When asked about the difference between an urban campus and a pastoral one, he paraphrased university architect Ray Casati: In an urban campus you have jewel-like green areas in a sea of buildings. In a pastoral campus you try to build jewel-like buildings in a sea of green.

Pointing out the swamp

along the Jordan River north of the Musical Arts Center, Hagen mentioned bald cypress trees, skunk cabbage, white dogtooth violets, and bluebells growing there. It may be an eyesore for some people,

he said, but I like it.

46

Students are attracted by the beauty of the campus, stated Michael Crowe, assistant director for campus maintenance and university horticulturalist. That confirms our idea of why we’re here. We’re a business, trying to attract customers, and we treat the people we deal with on campus as customers.

David Smith, university landscape architect, spoke about the unexpected consequences when Mitchell Hall was removed from the Old Crescent. It allowed new perspectives for other buildings: It actually gave them a backyard. Those are very beautiful buildings, from whatever side you’re looking at them. So the decision was made to continue with the philosophy of the woodland campus and to maintain that backyard as an open green space.

Citing Robert Frost’s poem Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,

Terry Clapacs, the director of the physical plant, suggested: Our hope is that as you cross campus, you find many places where you stop and you look and it’s beautiful, and you take that experience away with you.

47

7.5 Bloomington Campus Land Use Task Force

In 1995, Edgar Williams, vice president emeritus for administration, was appointed chair of the Bloomington Campus Land Use Task Force, initiated by President Myles Brand in the first year of his administration. At first, lands beyond the bypass were the subject of review, but it grew to include all property related to the campus. With a fifty-year planning horizon, the goal was to provide a basis for policy to govern both long-term and short-term land use.

The following year, in November 1996, the task force reported its findings and recommendations to the board of trustees. Chair Williams said that the university did not have formal procedures to decide on land use; the task force recommended the establishment of a university-wide permanent land use committee. The idea of designating a land bank, with various parcels of land [that] may be dedicated for periods of time for certain usage, keeping the highest priority for both academic and academic support services,

was also suggested. Three areas were identified: the land between Indiana and Woodlawn Avenues from Seventh to Tenth Streets, the land across Seventeenth Street from the athletic complex and west and south of the alumni center, and the land north and east of the State Road 46 Bypass.

The task force went on to recommend that one of the best uses at this time for some of the land north and east of the SR 46 Bypass is for golf courses,

with the suggestion that the land would be designated for a specified time period [of] 20–25 years

to accommodate any private investments. They asked the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics to prepare a plan involving the use of private funds only of the enhancement and development of golfing facilities that will better serve the rapidly increasing user rate.

They cited as evidence the 43,000 rounds played on the IU course the previous year. It is almost impossible to maintain that course,

Williams stated, and to meet the increasing demand.

Addressing other uses of the lands beyond the bypass, the task force recommended that the skeet and trap range and the police firing range be relocated and the lease agreement with the Sycamore Valley Gun Club be terminated. Using that ground for shooting sports and training for a third of a century with no accidents, the club had certainly been a good neighbor,

but increasing residential development in the area beyond the campus necessitated a change.48 The next June, Athletic Director Clarence Doninger mentioned the golf course in his report to the trustees. Still under study was whether to add nine or eighteen holes to the course, with future fundraising a given.49

7.6 Council for Environmental Stewardship50

In the fall of 1996, Paul Schneller, coordinator of professional development for the physical plant, met with the IUB Professional Staff Council to float the idea of implementing a campus environmental stewardship program. The council created an ad hoc Green Committee

consisting of staff members from a variety of areas to explore the idea.51 Staff council president Tim Rice, with the purchasing department, received the endorsement of IU President Myles Brand in January 1997 for an environmentally friendly campus, with the recommendation that the committee work with Vice President for Administration J. Terry Clapacs and his staff. With administrative and financial support from Ken Gros Louis, vice president for academic affairs and Bloomington chancellor, a half-time position of environmental stewardship coordinator was created in August to assist with the initiative.

In January 1998, Gros Louis hosted a meeting with vice presidents, deans, and other campus leaders to launch the environmental stewardship initiative. Featured speakers were Oberlin professor David Orr, a leader in campus ecology efforts, and Ball State University representatives who discussed their campus greening

program and the biennial national conferences on greening the campus.

Working with both the academic structure and the operational departments of IU, the Council for Environmental Stewardship (CFES) was formed soon after and had its first meeting in March. Members—around forty to start—represented a variety of offices, departments, schools, and organizations. The mission was to engage students, faculty and staff in academic programs and administrative efforts that enhance our campus environment and contribute to a healthy and sustainable world.

52 The council, growing out of a national movement for campus ecology, harnessed disparate efforts by individuals and small groups to make positive changes in the campus environment by developing formal communication channels between the university’s campus operations and its varied academic programs of research and teaching.

7.7 Staying the Course

At the end of August 1999, IU officials revealed plans to negotiate with a private developer to build and operate a Jack Nicklaus–designed championship golf course and associated facilities on the IU campus. The proposed location was Sycamore Valley, where until recently the gun range had been located, and adjacent to the existing golf course, which was showing its age and lack of professional design. The project fulfilled hopes that had been nurtured for years by the athletic department and their supporters.

Reaction soon followed. A letter to the Herald-Times editor was titled IU Country Club?

and urged public discussion on the project. The Herald-Times published a staff editorial, Nicklaus Course Raises Questions.

Acknowledging that a Jack Nicklaus Signature Championship Golf Course operated by Arnold Palmer Golf Management must sound like a dream come true for area golfers,

the editorial wondered whether the proposed facility would be accessible to Hank and Helen Hacker.

It was clear that the proposal was for a private club; it was unclear how public use might be managed. The piece also raised questions about the financial arrangements between IU and the developer and the potential environmental impact of the course.53 Soon IU environmental scientists—plant scientist Keith Clay, water specialist Bill Jones, ecologist Dan Willard—sent a letter to the university administration outlining environmental concerns and recommendations.

In mid-October, the IU Student Association, at the urging of the Student Environmental Action Coalition, sponsored a forum to discuss the golf course project. Held in the law school, the forum featured speakers Professor Clay, Bloomington Parks and Recreation Natural Resources Director Steve Cotter, and IU Assistant Vice President for Real Estate Lynn Coyne. The informational forum turned into a grilling as opponents to the proposal, making up the majority of the 170 people packing the room, lambasted Coyne with tough questions concerning the proposal,

a student eyewitness reported.54 Answering questions for two hours, Coyne maintained, The goal is to integrate the design with environmental sensitivity,

with any environmental concerns, such as soil erosion, water quality, and wildlife habitat, to be addressed adequately. But most of the audience remained skeptical.55 For those folks, the forum also turned out to be an occasion to make connections with others of like mind.

Soon after the forum, about two dozen students and townspeople, with a sprinkling of faculty, formed an ad hoc group opposed to the new golf course. Open to all, it took the name of Protect Griffy Alliance. Its abbreviation—PGA—was an ironic play on the better-known shorthand for the Professional Golfers’ Association. Griffy Lake, which had served as Bloomington’s source of drinking water from 1925 to 1955, and its surrounding wooded watershed were the focus of concern, but the deeper issue was the propriety of private land use concessions within a public university. The existence of the Protect Griffy Alliance organization was spread by word of mouth, letters to the editor of the local newspaper, and frequent public meetings of the group. The group’s members had no common ideology save a concern for the natural environment represented by the Griffy watershed. Griffy Lake was fed by Griffy Creek, which flowed through Sycamore Valley.56

Questions about public access were outlined in November when Vice President Clapacs and Assistant Vice President Coyne briefed the University Faculty Council. IU students, faculty, and staff would have limited access to the private club if they did not purchase a membership, which would include initiation fees ranging from $1,000 to $10,000 with monthly fees ranging from $75 to $200. Coyne said the public-private partnership with the Indiana Club LLC development group was a way to add more golf holes on campus, a long-term goal of the athletic department. Trying to allay ecological concerns, Coyne said, Each hole will be custom fit to its environment.

Summarizing the negotiations, Clapacs observed, There is a line you can cross by making something too private,

adding, The negotiations are difficult but cordial.

57

On November 12, the Protect Griffy Alliance staged a protest, dubbed the Rally for Lake Griffy, at the Sample Gates, the main campus entrance on Kirkwood Avenue, attracting a large crowd. In a skit, PGA members, dressed up in costume as birds, trees, and fish, gave objections to the course plans and potential environmental harms. The other PGA members, dressed as golfers, pretended to beat them back with golf clubs. In the newspaper coverage of the protest, Christopher Simpson, IU’s vice president for public affairs and government relations, claimed that the university administration shared concerns over the environment, noting that the Nicklaus group had constructed golf courses on environmentally sensitive land, adding, They have a track record of preserving, and even improving, the environment.

Kara Reagan, a student member of PGA, disputed that assessment, stating, There is no such thing as an ecologically sensitive golf course.

58

The board of trustees scheduled a public forum the week after Thanksgiving, two days before they were to meet to consider leasing campus lands for the new course. The other issue needing trustee approval was the operating agreement between the developer and the university, tentatively scheduled for a January meeting. Further details about the leasing and operating arrangements between IU and the developer were released. The lease, comprising 311 acres, would be for fifty years initially, based on the land’s appraised value of $1.18 million. All state permits, including erosion control, would be obtained.59

On the eve of the trustees’ forum, the Bloomington Herald-Times filled in background information of the development company, Indiana Club LLC, which had been legally incorporated only in October. The three principals—Bob Whitacre, Tom Rush, and Mark Hesemann—were IU alumni, and their company also was connected to University Clubs of America, an organization that creates, develops and manages golf resort facilities around the country for colleges and universities.

Hesemann, an executive with Golden Bear International, the firm headed by Jack Nicklaus, who achieved fame as a golfer before turning to the development of golfing facilities, had seen the Pete Dye–designed Purdue course and thought it would be a coup

to bring something similar to IU. He was also on the advisory board of the IU Kelley School’s Sports and Entertainment Academy. Hesemann connected with Whitacre and Rush and produced a plan for a private golf resort at no cost to the university except exclusive use of a substantial chunk of campus land.60

The morning of the trustees’ forum, professor of geological sciences Michael Hamburger wrote a Herald-Times editorial, asking an obvious question: Why is it that this plan was undertaken with virtually no involvement of IU geologists, biologists, and environmental scientists with expertise in the areas of soil erosion, groundwater contamination, ecology, limnology, and wildlife biology?

61

Chaired by trustee Fred Eichhorn, the forum took place in the Frangipani Room of the Indiana Memorial Union. Eighty-five people signed up to speak; sixty-one were opposed to the project, five were neutral, and nineteen were in favor. (Due to time constraints, sixty-seven individuals actually spoke.) After two hours, the forum moved to the Whittenberger Auditorium for three more hours. Proponents were mostly connected already to the project or were members of the men’s IU golf team, with some economic development and tourism officials. Many more opposed the plan. These citizens ranged from an angry ex-librarian to the venerable George Taliaferro, who stated,

62 Professor Hamburger presented a petition with 300 faculty signatures in opposition; Protect Griffy Alliance had one with 2,000 community signatories. The near-unanimous public outcry, We don’t need another golf course. And the university doesn’t need to further isolate itself from the city and the county.

including numerous little old ladies in tennis shoes saying

might have given the trustees pause. And pause they did. The next day, John Walda, president of the board of trustees, announced the postponement of a decision on the land lease to Indiana Club LLC until January 21 as well as the creation of an ad hoc committee of students, faculty, and administration to study the issues raised by the proposed course.63 In an editorial, the Indiana Daily Student wondered whether the delay was we’ll lie down in front of your bulldozers,

to give the trustees time to think, or to give opponents time to forget.

64

The Protect Griffy Alliance kept up the pressure, with phone calls, flyers, yard signs, newspaper editorials, and interviews on radio and TV, through the university’s winter break. On January 13, a group of faculty members submitted an alternative proposal for the Griffy land for a teaching and research preserve in the natural sciences. One of the proposal’s developers, biology professor Clay, noted that there had been no response to a previous letter recommending amendments to the golf course plan to mitigate possible environmental impacts. He said that a potential compromise might emerge, but so far the administration hasn’t given us any compromise positions.

65

The trustees and President Brand received an unusual letter that same week, from music teacher Daisy Garton, an IU alumna and donor, whose family homesteaded in the Griffy watershed about 1814. When Griffy Creek was dammed for the city water reservoir in the 1920s, her grandfather was forced to sell some bottomland, and he bought other land in the vicinity, which she inherited in 1937. In the early 1950s, the IU administration wanted to buy her property, for educational purposes.

Garton resisted but eventually sold part of the farm. When she learned that it was to be used as a golf course, she thought that was ridiculous.

Now, over four decades later, the golf resort plan would affect the remaining lands on Griffy Creek. Incensed, she wrote, I do not believe this endeavor is consistent with the educational mission of the university, or its public character…. I therefore join with many other citizens in asking that you preserve this land in its natural state, for the education and enjoyment of all.

66

In order to finance the fight, the PGA coalition held a benefit Lake Griffy Concert

in the historic Buskirk-Chumley Theater on January 16, a Sunday evening. It was a showcase of concerned local speakers and performers, some with national reputations, on behalf of a beloved local landmark. Musicians performing included Carrie Newcomer, Malcolm Dalglish, the Dew Daddies, Vida, and the 4th Street Irregulars. Keynote speakers were IU professor of English Scott Russell Sanders and local writer James Alexander Thom. Information was available in the lobby, where two online computer terminals were located so people could email their objections directly to IU officials. The atmosphere was electric in the packed house of seven hundred. The emcee, Professor Hamburger, proclaimed, Tonight we’re here to motivate, stimulate, vibrate, and, if necessary, castigate and repudiate!

The concert was a success, raising $5,000 for PGA.67

The day after the concert, the IU trustees’ office announced that the private golf resort proposal was canceled. They explained, The Trustees recognize the potential for the incongruence of mission between a public university and a golf club, which includes private membership.

President Brand cited two reasons: a private club within a public university, and the various faculty objections, to which the trustees listened carefully.

68

7.8 Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative

After the trustees formally designated some lands for the IU Research and Teaching Preserve in 2001, the Council for Environmental Stewardship continued its work.69 During the 2001–02 academic year, its environmental literacy working group decided that basic knowledge of the environment should be a competency of all graduates. To that end, they updated the list of environment-related courses at IU and surveyed other universities to determine whether a basic course in environmental literacy was a curricular requirement. Less than 10 percent of the institutions surveyed required such a course, although many offered similar courses as electives. Working group members developed a detailed proposal for a faculty seminar series to help create a freshman environmental literacy course.70 The next year, modest funding for the Environmental Literacy seminar was acquired, a wide variety of IU speakers and participants were recruited, and keynoters David Orr from Oberlin College and Christopher Uhl from Pennsylvania State University were confirmed for the fall 2003 event.71

The seminar series addressed two key questions: What should an environmentally literate person actually know?

and What teaching and learning strategies are most effective in promoting this level of environmental literacy campus-wide?

72 Weekly speakers and commentators from a variety of disciplines and perspectives approached these fundamental questions. The series was co-coordinated by faculty in biology and anthropology in collaboration with Campus Instructional Consulting, assisted by graduate students in SPEA and biology. Presenters included faculty from anthropology, biology, English, law, physics, religious studies, and SPEA, among others. Faculty and graduate students, as well as several staff members, participated in the lively seminar. Interest in continuing the discussion was so great that the seminar series continued over the spring semester.73

In addition to the knowledge shared and discussed, an attempt was made to address the seminar’s animating questions in a short position paper. The result, Environmental Literacy: A Pedagogical Approach to Greening IU,

was a précis of orienting philosophy, learning goals, and strategy.74 Because of the success of the seminar, the group spun off and took on a new name—Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative (ELSI)—to continue this work.

In the fall 2004 semester, a second, more informal seminar series was held, focused on the idea of greening IU and planning steps to institutionalize the twin aims of environmental literacy and campus sustainability. By August 2005, a small group of the larger ELSI body developed a proposal, Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative at Indiana University: Strategy and Institutional Structure,

for consideration by the IU administration. The organizational design included a sustainability coordinator (full-time professional staff member reporting to the chancellor or dean of faculties) and joint participation from CFES and ELSI in a campus-wide advisory board. Using temporary working groups to organize projects would be continued. The project’s annual budget was nearly $200,000.75

In October 2006, many members of ELSI signed a letter to Provost Michael McRobbie urging the appointment of a task force on sustainability. Vice President Terry Clapacs appointed the task force in March 2007. Students, faculty, and staff comprised the sixteen-member group, aided by more than one hundred individuals in various working groups. Their 122-page report, Campus Sustainability Report, was issued in January 2008.76 One of its main recommendations was to create an Office of Sustainability on the Bloomington campus, thereby beginning another chapter of the university’s response to living within its environmental means.

7.9 The Journey toward Sustainability

The year 2009 was catalytic for the future of the Bloomington campus. On the organizational front, the IU Office of Sustainability was established in March, with dual reporting lines to campus leadership of academic affairs and facilities administration. Architect and educator William M. Bill

Brown was selected as the founding director. Before long, students, faculty, and staff were engaged in a comprehensive program of assessing various aspects of the campus environment with the overall goals of improving resource use coupled with environmental education, and a strong student internship program began.77

In April, the field laboratory at the IU Research and Teaching Preserve was completed, providing research and classroom space. Located near University Lake, the lab followed the principles of green construction and was certified at the silver level by LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), an international metric. The field lab was the first IU building to be LEED-certified.78

In June, the limestone buildings on campus were highlighted by a pocket-size publication, Follow the Limestone: A Walking Tour of Indiana University.79 Brian Keith, a limestone expert employed by the Indiana Geological Survey, wrote the twelve-page guide explaining the architectural features and styles of the university’s signature building material.

Six months later, in October 2009, Indiana University was catapulted onto the world stage when political science professor Elinor Lin

Ostrom was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for her work on economic governance and the management of common property. Ostrom had worked at IU for forty-five years and co-directed the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis with her husband, Vincent Ostrom, also a professor of political science. She was the first woman to receive the prize, which had been awarded since 1969. Much of her research focused on how humans devise cooperative strategies outside of markets or governments to manage natural resources—such as fish stocks, lakes, and groundwater—in sustainable ways, using the tools of social-ecological analysis.80

In 2010, continued progress toward campus sustainability was maintained. The 2008 Campus Sustainability Report also informed a new planning document for IUB. The IU Campus Master Plan was published by the SmithGroupJJR firm in March 2010 after a three-year period of analysis and refinement. The most substantial and comprehensive plan of its type ever developed for the campus,

President McRobbie declared, adding, Sensitive to the great traditions of the campus while describing a carefully conceived path to an even more impressive future.

81 Five key themes animated the plan’s vision: promotion of unique natural features, preservation and reinvigoration of the core, an embrace of the Jordan River, a commitment to a walkable campus, and the creation of diverse campus neighborhoods. Affirming the continued relevance of the historic structures and distinguished open spaces,

campus development should emulate the quality and planning principles employed in the historic core.

82

Early in the 2010 spring semester, the book Teaching Environmental Literacy: Across Campus and Across the Curriculum was published. Edited by faculty members Heather Reynolds, Eduardo Brondizio, and Jennifer Robinson, it contained ideas from the Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative faculty seminar a few years earlier.83 In February, the 147-page Greening the IMU: Eco-Charrette Report was released, providing a summary of a charette exercise in December 2009 to explore ways to make Indiana Memorial Union operations and maintenance more environmentally effective.

Seventy-two individuals (professionals, students, faculty, and administrators) participated in the two-day charette, perhaps the first ever held on campus with an explicit sustainability focus.84

During the 2010 fall semester, the College of Arts and Sciences sponsored a themester

focused on the environment. Entitled sustain·ability: Thriving on a Small Planet,

specially themed coursework, lectures, art installations, movies, and other programs were abundant. In November, writer and activist Wendell Berry came to campus to deliver the Patten Lectures as part of the themester. Biology professor Heather Reynolds organized an interdisciplinary group of students, staff, and faculty as the Dunn’s Woods Project to research, restore, and educate about this iconic woodland. Much of the effort was to mitigate the invasive purple wintercreeper (Euonymus) and to reintroduce native plants to restore biodiversity. Two years later, Latimer Woods, part of the City of Bloomington parks and trails system, was added and the name expanded to Bloomington Urban Woodlands Project to pursue community partnerships.85

7.10 The Bicentennial Era

Mindful of the university’s two hundredth anniversary in 2020, the Office of Sustainability adopted a set of twenty aspirational goals to guide the next decade of work. These goals were organized into categories including leadership; academic programs; energy, atmosphere, and the built environment; transportation; food; environmental quality; and funding.86 Similar goal-setting and planning efforts occurred within university administration in anticipation of the bicentennial.

In December 2014, the board of trustees approved the Bicentennial Strategic Plan, which was built on ten Principles of Excellence that articulated the aims of the university’s mission to provide superior education, research, and health sciences and services. Number eight, Building for Excellence, addressed the physical plant: Ensure that IU has the new and renovated physical facilities and infrastructure that are essential to achieve the Principles of Excellence, while recognizing the importance of historical stewardship, an environment that reflects IU’s values, and the imperative to meet future needs in accordance with long-term master plans.

87 Among the action items were the renovation of the Old Crescent area to make it the core of student academic life once again and the validation of all new major buildings with the LEED Green Building Certification System at the gold level or above.88

Another university-level initiative was the establishment of the Office of the Bicentennial in 2016 to coordinate historical and commemorative programs and activities across all campuses. Guided by a report from the Bicentennial Steering Committee that articulated goals, principles, and values, the bicentennial office organized its work under two dozen signature projects. Among the major categories were historical markers, archive development, publications and media, oral history, and campus beautification.89 The first IU historical marker was installed on the IUB campus, honoring Professor Elinor Ostrom, in the fall of 2019, on the south side of Woodburn Hall.90

The bicentennial office supported a third wave of marking campus boundaries with gateways as part of the campus beautification project. During the first wave, in the 1920s, tall limestone gates punctuating low limestone walls were installed along Third Street. The second effort occurred in 1987 when the main campus entrance received the Sample Gates. This new effort was to mark different edges of the campus boundaries. We really didn’t have our major gateways identified,

said university landscape architect Mia Williams. It wasn’t clear to people where campus proper started and stopped …it’s about a sense of place. We’re saying,

91 Four new gateways were constructed, along with the relocation of an existing set of gates. The largest was a limestone monolith at Dunn Street and State Road 46 Bypass, consisting of a sixty-one-foot tower reminiscent of the bell tower on the Old Crescent and nine-inch carved letters proclaiming INDIANA UNIVERSITY. Another, smaller set of gates, given to the university a half century before by the Chi Omega sorority, was moved to Woodlawn Avenue and the State Road 46 Bypass, in front of the baseball and softball fields. The gate at Third and Union Streets marked the southeast corner of the campus. On the southwest corner, at Third Street and Indiana Avenue, a similar gate was constructed, a legacy gift from law alumnus Lowell E. Baier. The last gate, completed in 2018, was installed at the corner of Seventh Street and Indiana Avenue, at Dunn Meadow.92 The limestone gateways not only provided helpful landmarks but also tastefully reinforced the signature building material.93Hey, you’re at Indiana University.

In office from 2007 to 2021, the McRobbie administration pursued a vigorous program of facilities development, with new and renovated buildings across the campus, guided by the 2010 master plan. Two signature projects that were completed during the bicentennial year are instructive. One was rebuilding the golf course, dating to 1954, to championship standards—a dream long deferred. Named after a major donor, the Pfau Course at Indiana University was designed to take advantage of the forested setting and to offer golfers a demanding test of skill.94 The other project was the Arthur Metz Bicentennial Grand Carillon. Fifty years prior, right after IU’s sesquicentennial celebration, the original Metz Carillon was dedicated atop a hill on North Jordan Avenue. Played by faculty and staff of the School of Music, it was one of only six hundred carillons worldwide. Decisions were made to relocate the instrument closer to the heart of the campus, in the IU Arboretum (named in honor of Jesse and Beulah Cox), and to increase the number and size of the bells to qualify as a grand carillon—a rare distinction. Rivaling the tallest structures on campus, the cylindrical support holding the chimes, faced in limestone, elevated the bells so the sound carried for nearly two miles. Like the Student Building bell tower, installed more than a century ago, the new grand carillon promises to add to the remarkable soundscape of the campus.95

7.11 A Campus Legacy

In 2017, Indiana University Press published Indiana University Bloomington: America’s Legacy Campus. Authored by Terry Clapacs, former vice president for university administration and facilities, it was the inaugural volume in the bicentennial Well House Books series.96 The book contained an encyclopedic survey of the buildings and grounds of the flagship campus. Told from an insider’s perspective, the volume’s focus was architectural, but stories of campus life enlivened the text. In the introduction, Clapacs gave his considered opinion after his forty-year career in administrative stewardship: In the midst of the gently rolling hills of southern Indiana is America’s most beautiful college campus.

Generations of students, staff, and visitors would heartily agree.97

The image of IU has been shaped over time by the physical plant, contributing to the university’s identity as a place of learning. As Clapacs suggested, A significant core value and institutional commitment at Indiana University is to provide an environment that is more than pleasant and comfortable—the campus is meant to inspire and to instill the idea that one’s surroundings do make a difference.

98 By exploring that development historically, one can better understand the aspirations as well as the challenges of those who went before. There was no predetermined path to today’s campus. It was nurtured through the efforts of countless individuals as it grew through more than a century of academic dwelling.

Historically, there was an unswerving fidelity to the landscape of southern Indiana. Limestone, native trees, and running water were the hallmarks of the IUB campus and its raw materials as it expanded a hundredfold in size since 1885. Expressing the ideals of higher education, the campus has served as a physical embodiment of the agency and apparatus of learning. Simultaneously, it has supplied an enduring emblem of Indiana University, a richly textured symbolic image, available for immediate apprehension by all. Through the efforts of its academic community, generation after generation, the campus at Dunn’s Woods has made a place of learning and culture by remaining rooted to nature.

An addition had been discussed for years, and the trustees had hired architects in 1980 to prepare plans. IU had sought bonding authority for the $11 million project, but the state budget bill reduced the amount to $5 million in spring 1981. Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 02 February 1980” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 2, 1980), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1980-02-02; Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 May 1980” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 9, 1980), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1980-05-09; Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 March 1981” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 7, 1980), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1981-03-07; Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 05 December 1981” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 5, 1980), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1981-12-05; and John Fancher, “IU Trustees OK Law School Addition,” Herald-Times 15, no. 15 (December 6, 1981): 1, 8.↩︎

David Parkhurst, personal communication to author, March 11, 2019. (“Letter to Kenneth Gros Louis,” January 18, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files). At the Bloomington Faculty Council meeting on February 2, Gros Louis addressed the questions, hewing to the trustees’ public position; Indiana University Bloomington Faculty Council, “Indiana University Bloomington Faculty Council Minutes, 02 February 1982” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 2, 1982), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/bfc/1982-02-02.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos, “Law Addition Sparks Dispute over Woods,” Indiana Daily Student, January 19, 1982.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos, “Law School Expansion May Incapacitate Observatory,” Indiana Daily Student, January 21, 1982, 1.↩︎

“The Woods and the Law School Institution Addition,” February 1, 1982. Memo to Law School Student Body and Staff. David F. Parkhurst files, University Archives, Indiana University.↩︎

Save the Woods, “Save the IU Crescent Forest,” Real Times 6, no. 6 (February 19, 1982): 2. Originally circulated as "An Open Letter to Indiana University Alumni," February 11, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files, University Archives, Indiana University.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos, “Save the Woods Group Organizing to Protect Old Crescent,” Indiana Daily Student, February 10, 1982, 3. The Herald-Times published a photo of Tom Zeller and Donald Hutter tying ribbons, February 13, 1982.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos, “Law School Addition Plans to Be Resubmitted,” Indiana Daily Student, 1982-02-11. The Indianapolis Star covered the controversy, noting the main issues were the intrusion into the woodland preserve and the interference with Kirkwood Observatory, which recently had a $200,000 renovation. Barb Albert, “I.U. Group Launches Battle to Rescue Beloved Woods,” Indianapolis Star, February 12, 1982, 22.↩︎

Lisa Hooker, “RHA Votes to Ask the Trustees to ‘Save the Trees’,” Indiana Daily Student, February 18, 1982.↩︎

“Letter to Leonard Bernstein,” February 7, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.; Leonard Bernstein, “Letter to David F. Parkhurst,” February 13, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files; David Parkhurst to James Capshew, personal communication, March 11, 2019; Christopher Cokinos, “Bernstein Note Indicates Support for ‘Save the Woods’,” Indiana Daily Student, February 19, 1982.↩︎

“Plager’s Contempt on Compromise Out of Character for Law Profession,” Indiana Daily Student, February 19, 1982.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos, “Ryan Requests Look at Options for Law School,” Indiana Daily Student, February 25, 1982.↩︎

“Position Statement on the Proposed Law School Addition,” February 24, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.↩︎

“Letter to the Editor,” Herald-Telephone, March 2, 1982, 8.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos and Barbara Toman, “Trustees to Hear Law Expansion Opposition,” Indiana Daily Student, March 5, 1982; Barbara Toman and Christopher Cokinos, “Trustees Will Re-Evaluate Plan,” Indiana Daily Student, March 8, 1982, 1, 5; Christopher Cokinos, “State to Determine If Law Applies to IU Expansion,” Indiana Daily Student, March 12, 1982; John Fancher, “Law School Addition Still Up in the Air,” Herald-Telephone, March 6, 1982, 1.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 06 March 1982” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 6, 1982), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1982-03-06; Toman and Cokinos, “Trustees Will Re-Evaluate Plan”.↩︎

John Fancher, “IU Law School Addition Will Not Harm Trees,” Herald-Telephone, March 7, 1982, 1.↩︎

Jenny Ferguson, “Working to Save the Woods, Ryan Makes His Feeling Heard,” Indiana Daily Student, March 1, 1982. For the Opinion Board.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos, “New Addition Plan Would Save Woods,” Indiana Daily Student, April 2, 1982. Thus, the legal status of the plan was rendered moot. See Cokinos, “State to Determine If Law Applies to IU Expansion”, p. 2; Christopher Cokinos, “Law School Expansion Inquiry Buried,” Indiana Daily Student, March 31, 1982.↩︎

Barbara Toman and Christopher Cokinos, “Trustees Approve Addition Plan,” Indiana Daily Student, April 5, 1982; John Fancher, “Law School Addition OK’d,” Herald-Telephone, April 4, 1982; John Fancher, “Law School Plan That Saves Woods Moves Ahead,” Herald-Telephone, April 3, 1982; Sheldon J. Plager, “Letter to Alumni and Friends of the University and the Law School Community,” April 8, 1982.↩︎

Michelle Slatalla, “How the Trees Were Saved, Law Addition Flap Is Finally Over,” Indiana Daily Student, April 8, 1982. For the Opinion Board.↩︎

“Letter to David F. Parkhurst,” April 30, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.↩︎

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 April 1982” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, April 3, 1982), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1982-04-03.↩︎

John B. Patton, “Location to the Natural Areas Committee,” June 30, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files, University Archives, Indiana University.↩︎

Christopher Cokinos, “Wells: University to Develop Campus Natural-Areas Policy,” Indiana Daily Student, April 30, 1982, 2.↩︎

Although not a new idea (first proposed by Rey Carlson’s outdoor education classes before 1960), its [sic] been the subject of many planning efforts (including a preliminary master plan by a student in my R-530 planning class in 1971).

John M. Ross, “Letter to Herman B Wells,” April 27, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.↩︎Built in 1925, it was called Memorial Stadium and was constructed with funds from the Memorial Fund drive. In 1960, a new stadium was built on Seventeenth Street. Confusion about the old and new Memorial Stadiums was addressed by the board of trustees in 1968, 1970, and 1971, with the newer one designated Memorial Stadium and the older one Tenth Street Stadium.↩︎

James H. Capshew, Herman B Wells: The Promise of the American University (Bloomington; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press; Indiana Historical Society Press, 2012), 343.↩︎

“Charge to the Class,” May 8, 1982. Indiana University commencement location, Indiana University Archives/C45/John Ryan Speeches.↩︎

J. Terry Clapacs, Indiana University Bloomington: America’s Legacy Campus (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 354–59.↩︎

“Indiana University’s Woodland Campus,” View 12 (2012): 25–27.↩︎

“Program for the Rededication Ceremony for Indiana University’s Owen Hall and Wylie Hall, October 18, 1985” (Bloomington: University Printing Services, 1985).↩︎

Juliet Frey, ed., “Islands of Green and Serenity: The Courtyards of Indiana University” (Bloomington: Indiana University Publications, 1987).↩︎

“Remarks at the Sample Gates and Plaza Dedication” (June 13, 1987). John Ryan Speeches, Indiana University Archives/C45.↩︎

“Remarks at the Sample Gates and Plaza Dedication” (Indiana University Archives, June 13, 1987). John Ryan Speeches, Indiana University Archives/C45.↩︎

The Campus as a Work of Art (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1991).↩︎

The top group of thirteen, which all received nineteen out of twenty points, all received the maximum five points for urban space and overall appeal. They differed by one point on either architectural quality or landscape. Indiana received a five on landscape and four on architectural quality. The first four places were: Stanford, Princeton, Wellesley (four on landscape), and Colorado (four on architectural quality). (The Campus as a Work of Art), pp. 155-156.↩︎

George Milburn Beck (1895–1981), a Bloomington native, began working at IU’s physical plant in 1910, first as a janitor and then as a gardener, becoming campus foreman in the 1930s. After the war, he was supervisor of grounds, retiring in 1960 with fifty years of service. Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 14 July 1961–15 July 1961” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, July 14, 1961), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1961-07-14.↩︎

Wells began his undergraduate career in 1921, seventy-one years before the article was written. (“Conversations about the Bloomington Campus: It Isn’t Easy Being Green (but Planning Ahead Helps),” The College 16, no. 2 (1992): 8–11), p. 8.↩︎

Charles W. Hagen Jr. (1918–1996) earned his Ph.D. in botany from IU in 1944 and spent his entire career there, retiring in 1983, as both a professor and an administrator. He was chair of the Arboretum Planning Committee. Collins, p. 9–10.↩︎

Collins, pp. 10–11. Michael J. Crowe (1955–2010) was instrumental in the development of IU’s nursery and flower production programs. He was serving as director of facilities at the time of his death. Mitchell Hall, a wood frame building constructed at the same time as Wylie and Owen Halls in 1884, had seen hard use, many additions, and renovations to the point that little of the original fabric was left. There was controversy over its demolition. See Dolores M. Lahrman and Delbert C. Miller, The History of Mitchell Hall, 1885–1986 (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives, 1987).↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 01 November 1996” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 1, 1996), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1996-11-01.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 27 June 1997” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, July 27, 1997), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1997-06-27.↩︎

In the interest of full disclosure, I was a member of the council and its successor organizations.↩︎

Members were, in addition to Schneller: Jeff Kaden and Jeff Owens (physical plant), Ron Jensen (optometry), Bob Ensman (chemistry), Ted Alexander (environmental health and safety), and Mark Lame (SPEA). Council for Environmental Stewardship, “Annual Report,” 1998–1999, p. 2.↩︎

James H. Capshew, “IU Country Club?” Herald-Times, September 4, 1999; James H. Capshew, “Nicklaus Course Raises Questions,” Herald-Times, no. editorial (September 8, 1999).↩︎

Jonah M. Busch, “The Protect Griffy Alliance and the Golf War: Collective Action at Its Finest” (April 28, 2000). seminar paper, Indiana University.↩︎

Mike Wright, “Issues Raised about Golf Course’s Impact,” Herald-Times, October 13, 1999.↩︎

For example, Jerry Merriman, “How Should We Grow?” Herald-Times, November 10, 1999. letter to the editor.↩︎

Mike Wright, “IU Students, Staff to Have Golf Access,” Herald-Times, November 10, 1999.↩︎

Mike Wright, “Golf Course Opponents Dress Like Fish, Trees,” Herald-Times, 1999-11-13; Indiana Daily Student, November 15, 1999.↩︎

Mike Wright, “Trustees Want Public Input on Golf Course,” Herald-Times, 1999-11-24.↩︎

Mike Wright, “Group Behind New IU Golf Course Includes Alumni, Development Firm,” Herald-Times, November 30, 1999.↩︎

Michael Hamburger, “Editorial,” Herald-Times, November 30, 1999.↩︎

Mike Wright, “Critics Flock to Golf Forum,” Herald-Times, December 1, 1999; Busch, “The Protect Griffy Alliance and the Golf War,” 4–5. seminar paper, Indiana University.↩︎

Mike Wright, “IU Delays Action on a New Golf Course,” Herald-Times, December 2, 1999.↩︎

Indiana Daily Student, December 7, 1999, cited in Busch, “The Protect Griffy Alliance and the Golf War.” seminar paper, Indiana University.↩︎

Mike Wright, “Golf Course Alternative Offered,” Herald-Times, January 14, 2000, A1, A9.↩︎

Daisy Garton, “Letter to Trustees of Indiana University, President Myles Brand, and Members of the Higher Education Commission,” January 12, 2000.↩︎

David Horn, “Golf Course Opponents Jam Benefit Concert,” Herald-Times, January 17, 2000.↩︎

Erin Nave and Kara Saige, “Golf Course Cancelled,” Indiana Daily Student, January 18, 2000.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 May 2001” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 4, 2001), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2001-05-04.↩︎

Council for Environmental Stewardship, “Annual Report,” 2001–2002, 2–3.↩︎

Council for Environmental Stewardship, “Annual Report,” 2002–2003, 3.↩︎

An earlier iteration:

What constitutes the basic level of environmental literacy that all citizens should have?

↩︎ELSI’s History,

from archived ELSI website.↩︎Environmental Literacy: A Pedagogical Approach to Greening IU,

2004, from archived ELSI website.↩︎Environmental Literacy and Sustainability Initiative at Indiana University: Strategy and Institutional Structure,

2005, from archived ELSI website. The proposal coordinators were Eduardo Brondizio, Victoria Getty, Brianna Gross, Diane Henshel, Catherine Larson, and Heather Reynolds.↩︎IU Task Force on Campus Sustainability, “Campus Sustainability Report” (Bloomington: Indiana University, January 7, 2008).↩︎

Nick Cusack, “First IU Sustainability Director Named,” Indiana Daily Student, February 19, 2009; William M. Brown and Michael W. Hamburger, “Organizing for Sustainability,” in Enhancing Sustainability Campuswide, ed. Bruce A. Jacobs and Jillian Kinzie, New Directions for Student Services 137 (Wiley, 2012), 83–96. See also Bruce A. Jacobs and Jillian Kinzie, “Editors’ Notes,” in Enhancing Sustainability Campuswide, ed. Bruce A. Jacobs and Jillian Kinzie, New Directions for Student Services 137 (Wiley, 2012), 1–6.↩︎

Brian D. Keith, “Follow the Limestone: A Walking Tour of Indiana University” (2009; repr., Bloomington: Originally published June 2009 by Indiana Geological Survey; Bloomington/Monroe County Convention; Visitors Bureau; republished July 2013 by Indiana Geological Survey; Visit Bloomington; current edition published July 2018 by Indiana Geological; Water Survey; Visit Bloomington, July 2018). In 2015, a digital version was produced: B. D. Keith, B. T. Hill, and M. R. Johnson, “Indiana University Campus Limestone Tour,” Digital Information (Indiana Geological Survey, 2015), https://legacy.igws.indiana.edu/bookstore/details.cfm?Pub_Num=DI02.↩︎

Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Press release↩︎

SmithGroupJJR, “Indiana University Bloomington Campus Master Plan,” March 2010. Michael A. McRobbie wrote the foreword.↩︎

Heather Reynolds, Eduardo Brondizio, and Jennifer Robinson, eds., Teaching Environmental Literacy: Across Campus and Across the Curriculum (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010). In the interest of full disclosure, I authored a chapter in the edited book.↩︎

“Greening the IMU: Eco-Charrette Report” (Bloomington: Indiana University, February 23, 2010).↩︎

Promoting healthy forests and reconnecting communities with their woodlands↩︎

IU Office of Sustainability, “Office of Sustainability 2020 Vision,” 2010.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 05 December 2014” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 5, 2014), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2014-12-05.↩︎