3 Inventing IU History

It will be seen that during the first generation of its history the Indiana University endured a continuous struggle…. Yet under its first president, during its first quarter of a century, it continued to do respectable and thorough college work. Under the advancing and more liberal policy of the last twenty years on the part of the State toward her institutions of higher learning, the institution, from being only a training school in the classics and mathematics, is rapidly pushing into the work of the university proper, and offers growing opportunities for advanced and original investigation.

—James A. Woodburn, Higher Education in Indiana

Between 1883 and 1885, a series of unforeseen and startling events set Indiana University on the long road to its current distinction as an American research university. Shedding its prior identity as an ordinary classical collegiate institution, the new campus with its fresh leadership provided energy to pursue ambitious educational goals and higher aspirations for its academic community. IU got in step with national trends in higher education, characterized by widespread university-building fueled by increasing student enrollments, a focus on research, and renewed commitments to serve society. To make sense of these changes as well as to further encourage the pursuit of lofty goals for the institution, the distinct genre of Indiana University history was invented in the 1880s by a trio of faculty working on individual projects, with some overlap and collaboration. History-making, through historical narratives, was a driving force as the university community confronted its previous sixty-odd years and envisioned a new path forward.

The quest to assemble a formal university history was made public with an announcement in the May 1883 issue of the Indiana Student. David D. Banta, president of the IU Board of Trustees, asked for help from the alumni and former students who have any old documents, such as class programs, catalogues, addresses of professors and presidents, or other papers pertaining to the University,

mentioning especially the 1854 or 1855 catalog of the Athenian Society.1 Banta issued this request to assist longtime professor Theophilus Wylie in preparing the first historical catalog

of the university. Student life at the small institution located on Second Street and College Avenue centered around class recitations and the self-governed literary societies, including the Athenian Society and its chief rival, the Philomathean.

The following month, the 1883 IU commencement featured an alumni reunion and the award of an honorary LLD (Doctor of Laws degree) to Andrew Wylie Jr., the eldest son of the first president, Andrew Wylie. The son, a member of the class of 1832, the third graduating class, had become a lawyer and was an associate judge of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia in Washington, DC, appointed by President Abraham Lincoln.

The alumni society, first constituted in 1854 in the wake of the campus fire, had been revived a couple of years previously after years of organizational neglect and recently had made efforts to lobby the Indiana General Assembly for increased support for the university. Their efforts paid off in March 1883, when legislation was passed that established a permanent endowment fund from the state.2

In July 1883, a catastrophic fire struck the deserted campus, burning the newest of the two main buildings, Science Hall, only ten years old. Since there were no eyewitnesses and a heavy rainstorm at the time, a lightning strike was assumed to be the cause. The building was a total loss, and the thirteen-thousand-volume library, collections of fossils and of fishes, physical and chemical apparatuses, and faculty books and papers were among the items destroyed.3

The fire set into motion actions by the IU Board of Trustees that would have far-reaching effects on the small collegiate institution. By August, trustees were debating whether to relocate the university. Some already thought that the ten-acre campus was inadequate, being hemmed in by the railroad on its western boundary since 1853 with its noise, vibration, and clutter. The fire became another argument to move. Bloomington, with its 3,000 citizens, was growing and had ample land for sale. The trustees looked at eleven parcels and decided to move the university to the eastern outskirts of the town, to a twenty-acre woodlot on the Dunn family farm.

3.1 From Seminary Square to Dunn’s Woods

Dunn’s Woods, purchased by the trustees for $6,000, became the site of the new campus. In September, the commissioners of Monroe County made a $50,000 donation toward construction costs to rebuild the university.4 The next month, science professor David Starr Jordan, away on a collecting expedition, wrote to IU president Lemuel Moss: I am glad to hear of the general brightness of the prospects of the institution. The Dunn’s Woods project I do not quite understand, but the location is certainly better among those great maples. I hope that you will let none be cut down, except when their removal is absolutely necessary.

5

The trustees hired Indianapolis architect George W. Bunting to design three buildings, two of brick and one of wood, and plans were submitted in November 1883. Ground was broken in April 1884 at the new campus, hopefully renamed University Park, and construction commenced using recycled bricks from the burned building. Meanwhile, professors and students soldiered on at the old campus, the ruins of Science Hall a daily sight.

Change was not limited to the built environment; it also extended to the university’s leadership. In the first semester of the 1884–85 year, a group of six students plus the janitor, Thomas Uncle Tommy

Spicer, drilled a small hole in the floor above one of the rooms in the surviving university building. There were rumors of an affair between President Moss, a Baptist minister and a married man, and the young professor of Greek, Katharine Graydon, a single woman. Through the spy hole, the students observed the two kissing and caressing and reported it to the trustees.6 The trustees, duty bound to launch their own investigation of this serious violation of social norms, set a hearing date for November 11. Graydon submitted her resignation letter on November 5, followed three days later by Moss. The trustees called off the investigation immediately, likely relieved that the university would not have to air its dirty laundry in public after all.7 The trustees appointed seasoned professor of languages Elisha Ballantine as acting president.

The trustee board immediately launched a search for a new president. Several candidates were considered from a list containing forty-seven names, but in the end, the trustees chose biology professor David Starr Jordan, a prominent ichthyologist on the faculty since 1879, as the seventh president of Indiana University.8 Trained at Cornell University and influenced by its progressive president, Andrew Dickson White, Jordan was a staunch Darwinian and an avowed proponent of the research ideal. He was a popular professor, taking students on natural history rambles in the area surrounding Bloomington and pioneering weeks-long expeditions to Europe, called summer tramps,

to sample aspects of natural as well as cultural history.

Jordan took office on the first day of January 1885, announcing: I believe our University is the most valuable of Indiana’s possessions. It is not yet a great University, it is not yet a University at all, but it is the germ of one and its growth is as certain as the progress of the seasons.

9

The IU trustees, headed by Banta, had faced three major challenges in the previous eighteen months: the burning of the best building on campus, the decision for a wholesale removal to a new site, and an unanticipated change of presidential leadership. Further changes were afoot in the expansion of the curriculum to embrace scientific fields, the reorganization of the faculty into departments, and the institution of the major

course of study for students. As President Jordan explained, The highest function of the real University is that of instruction by investigation, and a man who cannot and does not investigate cannot train investigators.

10

To some longtime faculty members, the pace of change provoked apprehension. Theophilus Wylie, granted emeritus status in 1886, wrote in his diary: New arrangements, new studies, new teachers, new modes of teaching, give me much anxiety.

11 Some others might have shared Wylie’s disquiet, but students were voting with their feet to come to the new University Park, as enrollments surged after 1885.

To improve faculty quality in the face of limited financial resources, Jordan began filling vacancies with professors from eastern institutions, but most failed to adapt themselves, appearing to feel that coming so far West was a form of banishment.

So, he took a page from Hoosier agricultural heritage and populated the faculty with homegrown talent. He started the Specialist’s Club for gifted students, and he promised talented recent IU graduates professorships when they had secured the requisite advanced training in the East or in Europe.

12 Among the many alumni he inspired to become Indiana faculty stalwarts were Joseph Swain, William Lowe Bryan, Carl Eigenmann, James A. Woodburn, David Mottier, and William Rawles.13

In the fall of 1885, classes opened on the new campus. The three new buildings—Wylie, Owen, and Maxwell (later renamed Mitchell)—contained classrooms, laboratories, and offices. The old College Building at Seminary Square was still being used for the IU Preparatory Department and large gatherings. Events of the previous two years uprooted the institution, and the new campus opened in 1885 without a sense of history,

as historian Howard McMains later noted.14

3.2 Inventors of IU History

As Indiana University worked through significant changes in the 1880s, a trio of faculty were working, separately and together, to craft the saga of the institution. Each brought different talents and angles of vision to the task of making sense of the recent changes. To be sure, the university had survived serious threats to its welfare, even its existence as an institution, almost since the beginning of instruction, but things were different this time. Nearly every aspect of the university—physical plant, curriculum, leadership, state relations—was affected. In the face of a period of major changes, there was an inevitable distinction to be made between the time leading up to the period and the time since. In simple terms, there was a clear before

and after.

That distinction, whether explicitly acknowledged or not, became the main armature around which the trio of faculty historians shaped their narratives about IU.

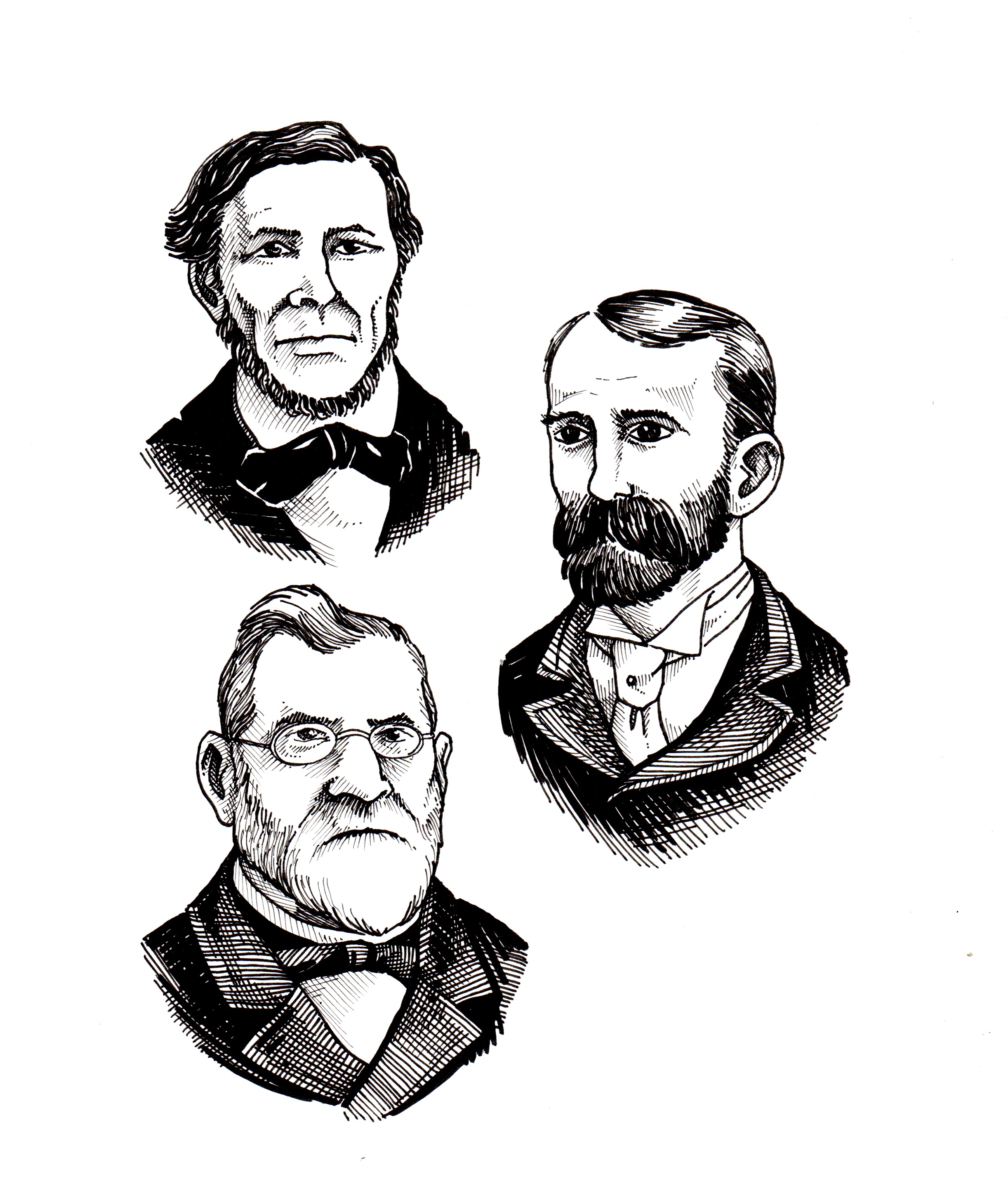

The first, in terms of seniority and length of faculty service, was Theophilus Wylie (1810–95). A younger half-cousin of the first president, Andrew Wylie, he was hired to teach natural science and chemistry in 1837. He taught many other subjects over his long teaching career as well. Wylie also served a variety of administrative posts, including librarian and president pro tem of the small university. Thus, he was in a good position when the board of trustees asked him, in 1881, to prepare a historical catalog documenting the history of IU for its first six decades. He was appointed IU vice president in 1882 but resigned from this position in June 1884 to free up more time for historical research and asked Banta for assistance.15

The second member of the trio was David D. Banta (1833–96), a former Indiana circuit court judge who became an IU trustee in 1877, serving as board president from 1882 to 1889. He was appointed dean of the newly revived law school in 1889, serving until his death in 1896. He received two degrees from IU: a Bachelor of Science in 1855 and a Bachelor of Laws in 1857. Banta, a successful lawyer and judge, was a self-trained historian, completing a history of the Presbyterian Church in Franklin, Indiana, in 1874. As president of the IU Board of Trustees, he was a key figure during the momentous transition in the university’s campus location and leadership from 1883 to 1885.

The trio’s last member, James Albert Woodburn (1856–1943), represented yet another, more recent, generation. Son of faculty member James W. Woodburn (1817–65), he had been baptized at seven months by Theophilus Wylie at Bloomington’s Presbyterian church.16 The younger Woodburn had been educated in Bloomington schools and attended IU, receiving a Bachelor of Arts in 1876 and a Master of Arts in history in 1885. In 1879, he began teaching in the IU Preparatory Department and later became a member of President Jordan’s Specialist’s Club for future faculty members. Securing a leave of absence from IU in 1886, Woodburn pursued a doctorate in history from Johns Hopkins University, studying in the famous seminar guided by Herbert B. Adams. In his absence, in 1888, he was promoted to associate professor of history at IU. After writing a dissertation examining the history of higher education in Indiana, he earned his Doctor of Philosophy in 1890.

Both Woodburn and Banta were IU alumni, and each became acquainted with Theophilus Wylie as college students. Starting in 1879, the trio spent sixteen years on the IU staff together until Wylie’s death in 1895, followed a year later by Banta’s passing. All were steeped in the traditions of the Seminary Square campus, but each had a different viewpoint based on their personal observations and associations. Wylie was in the final phase of his long teaching career and now embarking on a laborious accounting of all the people who had belonged to the university since 1820—students, faculty, presidents, and trustees. Banta, as president of the trustee board, played a key role in steering the university’s course in the turbulent mid-1880s. Pressed into service as the dean of the newly revived law school in 1889, he became a senior faculty figure too. Woodburn, nearly a half century younger than Wylie, was just starting his professorial career, albeit with a family background that had been connected to IU since the late 1830s.

3.3 Toward a Historical Catalog

When he started the historical catalog project in 1881, Wylie thought it would take him about three years. The intent of the work, according to the trustees’ request, was to showcase the university’s contribution to the state and the nation through the impact of its faculty and alumni. Taking on what he acknowledged as a very big task…if it is done as it ought to be,

Wylie sent out multiple rounds of postcards and letters soliciting information from former faculty and students as he endeavored to compile exhaustive lists and biographical portraits of professors, presidents, trustees, and students, both graduates and nongraduates, since the university’s beginning in 1820 as the state’s seminary of learning.

Wylie’s painstaking work was frustrated by the loss of university records and papers by the 1854 campus fire and the more recent burning of Science Hall in 1883. He sifted through surviving documents, year by year, for the comings and goings of students and faculty.17 His wide correspondence with alumni yielded a wealth of materials to replace missing records and other relevant information.

The lack of sufficient documentation and understanding concerning IU’s past was illustrated by a historical conundrum addressed by the trustee board in March 1884. In the midst of making plans for the new campus at University Park (and a few months before the Moss scandal broke), a point of clarification was raised about another, seemingly minor matter: The question of date on the University Seal was brought to the notice of the Board. After discussing the old date (1830) and the date of the organization of the Indiana Seminary (1820), the organization of the Indiana College (1828), and the Indiana University (1838), it was agreed by general counsel to fix the date of the seal at 1820, the other devices to remain as in the former seal.

18 Without relevant records to disclose the reason why 1830 was on the seal, the trustees apparently decided it was a simple mistake and removed the last X from MDCCCXXX. After the trustees changed the seal to correspond with the founding date of the institution’s earliest progenitor, the Indiana State Seminary, the trustees moved on to more pressing business.

Trying to piece together IU’s history during extensive institutional change was not easy for Wylie. On the verge of teaching on the new campus in September 1885, Wylie confessed his anxiety to his daily diary.19 In 1886, after successfully completing his final year of teaching in the new surroundings of University Park, Wylie was granted emeritus status for his forty-seven years of service.20 He was a creature of the old campus, retaining his emotional connection to Seminary Square. His living situation reinforced those ties. He had been living in Wylie House, the former home of the first president, for a quarter century and raised a large family there. Wylie persevered with his research and extensive correspondence with members of the university clan for several years after the center of campus life moved to Dunn’s Woods. As the scope and complexity of the historical catalog continued to evolve, Banta, who had done some research and writing about the university himself, became both a contributor to the volume and a member of the trustee committee supervising its production.

3.4 Creating a Foundation Narrative

By the mid-1880s, the university had survived for sixty years, with over 1,200 graduates. Stories of the institution’s past, leavened with folklore, had evolved into an informal oral tradition, passed from generation to generation. A main source of this oral tradition was physician David H. Maxwell, the first president of the board of trustees; the oral tradition was further amplified by his son, James Darwin Maxwell, also a trustee.

From Jefferson County, the senior Maxwell was a delegate at the convention that wrote Indiana’s first state constitution in 1816. That document mentioned that the state would provide, at some point in the future, a general system of education, ascending in a regular gradation from township schools to a State university.

21

Maxwell, with his wife and young son, moved to Monroe County in 1819, a year after the county was organized at the northern limit of white settlement. In 1820, the Indiana General Assembly passed an act to establish a state seminary of learning, to be organized by a board of trustees. Maxwell was among the original trustees and was elected president of the six-member board. In 1828, when the state legislature established Indiana College, new trustees were appointed, including Maxwell. He continued as board president for the next decade. In 1838, the Indiana General Assembly passed an act to establish a university in the State of Indiana

and a reconstituted board of trustees to oversee it.22 Maxwell was not among the original members of this twenty-one-person board, although he was appointed the following year, serving until 1852. He died weeks before the 1854 fire that destroyed the College Building.

His son, James Maxwell, also a physician, was an IU alumnus and served the board of trustees as their appointed secretary from 1838 to 1855 before becoming a trustee himself from 1861 to 1892, the year of his death.23

Both Maxwells, father and son, lived in Bloomington and were familiar figures in town and on the IU campus at the end of College Avenue. Their combined service as trustees spanned seventy years, from the very beginning of the institution in 1820 into the early 1890s. The main outlines of the oral tradition emphasized the institution’s continuity and created a narrative of linear progress. It ignored the inconsistent actions of the Indiana General Assembly and elided the real distinctions between seminary, college, and university in favor of a post-hoc vision of inevitable advancement.

Until his death in 1854, Maxwell was a regular figure on campus. Banta, who graduated in 1855, remembered him with great respect

and must have listened to Maxwell’s version of the foundation narrative many times.

His son, James Maxwell, was also a familiar sight until his death in 1892, and no doubt reiterated his father’s story.24 Indeed, all members of the trio who invented IU history had ample occasions to hear the origin story from a Maxwell—father or son or both.

When Banta, now the revived law school dean, was chosen to present the inaugural Foundation Day address in 1889, he spoke on the Indiana Seminary, crystallizing the informal oral tradition informed by Maxwell into historical doctrine. The story was that David Maxwell, acting as an unofficial lobbyist to the legislature meeting in Corydon in December 1819, pressed for the location of a seminary of learning in Monroe County. With the support of Governor Jonathan Jennings, a bill authorizing the creation of a state seminary was narrowly passed on January 20, 1820. Banta admitted in his narrative that no record, no tradition even, remains to tell the story of what he did, to secure legislative action on behalf of a State school.

Maxwell’s subsequent actions as a trustee over the next thirty years led Banta to declare that he was the Father of the Indiana University.

25

For the next five years, Banta gave Foundation Day addresses, elaborating on the history of the institution to 1850. With this official imprimatur, the origin story became further solidified as a linear chronicle of Indiana State Seminary (1820–28), Indiana College (1828–38), and Indiana University (since 1838).

After a decade of effort, Wylie’s historical catalog was finally published in 1890, under the title Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professors and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887. It contained an abbreviated chapter from Banta on the Indiana seminary, as well as a chapter on the university’s legislative history written by Robert S. Robertson, a trustee. The bulk of the book was filled with biographical sketches of students, professors, presidents, and trustees with short narrative sections covering the collegiate department and law school.26

Meanwhile, James Woodburn was away in Baltimore, on a leave of absence from IU to work on a Ph.D. in history. Shortly after Banta delivered his first Foundation Day address in January 1889, Woodburn wrote to him about IU history. Banta replied, Anything in my paper you find of service to you in your monograph you are welcome to use.

Banta talked about the Hoosier pioneers who were much in earnest in their desire for educational advancement

but they faced three main obstacles: In the first place the great poverty of the people and in the second the physical obstacles such as unprecedented sickness prevailing generally and the difficulties incident to a region so densely wooded as was Ind.; and in the third place want of models. Every thing [sic] had to be worked out of the green and it required the labor of 50 years to get the field ready.

27

Later that year, Woodburn finished his historical monograph, Higher Education in Indiana, and in 1890 received his doctoral degree. His mentor, Herbert Adams, was editing a series of studies, Contributions to American Educational History, for publication by the US Bureau of Education. Woodburn’s dissertation found a place in the series and was published by the bureau in 1891—his first publication with Ph.D. appended to his name.28

Woodburn hewed to the existing foundation narrative in his two chapters on the evolution of Indiana University, writing about the historical progression of seminary, college, and university in an unproblematic way. The view from the present was reinforced by eight illustrations of the buildings of the new campus at Dunn’s Woods and only one from the old campus at Seminary Square, still in use for the preparatory department. He also singled out the contributions of David Maxwell: In the establishment of institutions, it seems that the life and services of some one man are paramount and essential. In the establishment of the Indiana Seminary Dr. David H. Maxwell was the essential man.

29

The lack of institutional records, exacerbated by two great campus fires, combined with the perceived need to account for the university’s history in the 1880s, led to agreement among the three faculty members about the foundation narrative. For over a century, subsequent historians of IU have uncritically echoed that judgment about the institution’s origins and early development.

More recently, contemporary scholars are indebted to historian Howard McMains’s revisionist account of the early history of the institution that would become Indiana University. He examined the historical construction that the charter of the Indiana State Seminary was foretold in the state’s constitution, thus laying the bottom rail

for Indiana University, as every previous IU historian had written. McMains explained, The constitution had not…contemplated the seminary charter; the seminary charter had not contemplated the university.

But David Maxwell connected the two together: His narrative inserted the institution into the very origins of the state and linked constitution, seminary, and college into a seamless development…[and] also made a university in Bloomington seem inevitable.

30 By carefully reexamining both surviving documents and the political and social context, his article lends support to the contention that the foundation narrative created in 1889–91 was not a straightforward piece of historical reporting but an account shaped first by David Maxwell to lend legitimacy to the notion that the seminary was the seed of the university and then by subsequent historians to provide a comforting sense of institutional progress to the circumstances of their present day.

3.5 A Case of Collective Amnesia

The process of constructing a foundation narrative for the institution required a selective reading of past evidence. With the destruction of records and the limits of human memory, the dates of certain key events were lost to history or misremembered, at least for a time. One example occurred at the time IU’s origin story was being solidified. Recall that in 1884, the board of trustees, headed by David Banta, believing the University Seal to be misdated, changed the date on the seal from MDCCCXXX (1830) to MDCCCXX (1820). They thought it was a simple misdating of the seminary’s founding. Eight years later, Banta, now dean of the law school, reinforced that decision in his 1892 Foundation Day address, The

In his introduction, he spoke of inscriptions as historical evidence:Faculty War

of 1832.

There is one inscription very close to us that falsifies the truth of history. It is over the east front entrance of this College building. It states that the Indiana University was founded in 1830, and for the benefit of those who may not happen to know better, let me say that there is not a word of truth in that statement. The Indiana Seminary was chartered on January 20, 1820, the day we commemorate….I know of no excuse for the false record inscribed in the stone over the College door, and I know not whether it was the result of ignorance or of mistake. There is nothing connected with this institution which was founded in 1830.31

Banta devised a likely story to support the trustees’ 1884 interpretation that it was a simple mistake. Conveniently, it reinforced the narrative of linear progress from the seminary.

But 1830 did mark a historic date for the small collegiate institution: it was the first year that Indiana College granted degrees. After ten years of planning and five years of classes, four students finally finished the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in 1830. Now the institution had begun to have success in its raison d’être. In the eleven years following, another sixty-five students received their degrees. In total, eight classes (1830–37) were awarded degrees from Indiana College.32

On February 15, 1838, the Indiana General Assembly elevated Indiana College to Indiana University. Section 4 read: The said trustees shall cause to be made for their use, one common seal, with such devices, and inscription thereon, as they shall think proper, under and by which all deeds, diplomas and certificates and acts of the said corporation shall pass and be authenticated.

33 Several months later, in September, President Andrew Wylie received the following instruction from the board of trustees: Resolved That Pres’t Wylie be requested to procure a Seal for the University, with such engravings and devices as he may think appropriate, and also a [printing] plate for Diplomas.

34 In 1841, the trustee board approved the original university seal, with the date MDCCCXXX, with no further discussion.35 Diplomas were the primary documents affixed with the seal, but it was also carved on the stone portals of the second College Building in 1855 after the first College Building was destroyed by fire.36

Paying attention to context, there is a good argument that the seal’s original date was no error. The seal had a symbolic function and was featured on diplomas for certification and validation. In its early years, the institution was small and precarious. After the 1838 name change, it was still a small struggling college for many years, but its aspirations had enlarged as it met with success, year after year, in slowly increasing the number of its graduates. The 1841 trustees well knew that the true mark of institutional accomplishment was the completion of the recurring cycle of higher education—and there had been one dozen graduating classes at the time the seal was approved.

Four decades later, the context had changed substantially. In the immediate aftermath of the Science Hall fire that led to the purchase of Dunn’s Woods, the 1884 trustees were newly concerned about institutional history. Where was the university headed? Where had it been? Stories about the inevitable advancement of Indiana University from its precursors, Indiana State Seminary and Indiana College, provided a comforting narrative of linear progress in the past during a time of an uncertain present.

Moreover, annual commencements had become an ordinary feature of the campus calendar, involving dozens of graduates in the 1880s rather than the handful of the 1830s and 1840s. Interest had moved to the consideration of the institution’s statutory origins—the 1816 congressional land grant and the 1820 legislative act creating a seminary of learning. But some basic facts about the university’s operation, such as the date of the original University Seal or the date when classes started, were misremembered, and lost to collective memory for a time.37

3.6 Lack of Primary Documentation

Determining key facts in IU’s chronology has been hampered by a lack of primary documentation. Many early university records did not survive the campus fires. A prime example is the confusion about the date classes began at the state seminary. With primary sources unavailable, some university histories have claimed that classes began in 1824, and some have claimed 1825. In 1890, Banta used 1824 in his abbreviated essay The Indiana Seminary,

published in Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, by Theophilus Wylie.38 When Banta’s manuscripts were published in full in the IU Alumni Quarterly in 1914–15, editor Samuel Harding changed a couple of 1825 instances to 1824. In a long footnote, James Woodburn discussed the ambiguity in the 1940 History of Indiana University, Volume I: 1820–1902.39 He cites registrar John Cravens, who told him that he had found seemingly good authority for two dates—1824 and 1825.

Woodburn agreed with Cravens: For the benefit of future historians, the evidence for both dates is presented here.

40

Woodburn goes on to discuss various primary sources from outside university records, concluding with a citation of David Maxwell’s 1828 report to the legislature. The document never explicitly dated the beginning of instruction but can be interpreted as supporting the 1824 date. Woodburn’s final comment implied agreement: Perhaps on this evidence we can rest our case.

41 There things rested for three decades until 1970, when Thomas Clark published the first volume of Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer. Based on careful study, including an unearthed newspaper notice issued by the board of trustees, he determined that the beginning of classes at the seminary was 1825.42

In 1984, university archivist Dolores Lahrman assigned her assistant, Bruce Harrah-Conforth, to research the question again. He wrote The Beginning of Classes at Indiana University 1824 or 1825? A Study of Evidence

the following year. He argued for 1824, based on counting backward from David Maxwell’s 1828 report to the legislature that stated the institution had existed for four years. He dismissed the primary source that Clark cited in support of the 1825 date, claiming that it merely announced the first day of classes for a particular term, not the first day of classes ever at the seminary.

Meanwhile, the City of Bloomington planned to renovate Seminary Park and include important IU dates carved in limestone. In February 1987, Lahrman wrote to President John Ryan informing him of the city’s plan and lamenting the inconsistent dates for the opening of classes. Since the publication of Clark’s official history, there were some IU offices using 1824 and some 1825.

Rather than search for additional primary sources and do further historical research, the board of trustees accepted Harrah-Conforth’s report as definitive and passed a unanimous resolution acknowledging 1824 as the year and May 1 as the anniversary date of the beginning of classes at the State Seminary.

43 An IU news release was issued immediately: The resolution passed today by the trustees officially resolves that controversy and establishes 1824 as the date to be used in all future university publications.

44 It was not clear whether anyone noticed the irony of overturning a date determined by a reputable historian in the most recent official IU history in favor of a single, ambiguous document by a former trustee who was widely known as the father of Indiana University

in the origin story first set down in the 1880s.

A month later, the eighty-four-year-old university chancellor and former president Herman Wells sent President Ryan a note, copying archivist Lahrman: I disagreed with Clark’s finding when he made it, and so told him. I am happy, therefore, that further research has revealed that 1824 is the proper date.

45 Lahrman responded to Wells with thanks, saying it means a great deal to us to know that you have been for a long time in agreement. I was apprehensive about undertaking the research, since I love and respect Dr. Clark and hate to risk offending him, but it seemed that we had to try to determine the facts.

46 In his reply, Wells congratulated Harrah-Conforth on his research and Lahrman for initiating action.47

In 2008, Indiana Historical Bureau researcher Jeremy Hackerd made another run at the vexed issues of dating the beginning of classes. In charge of the Indiana Historical Bureau Historical Marker Program, Hackerd exercised due diligence when the City of Bloomington and Indiana University proposed a state historical marker to commemorate the site of the Indiana State Seminary. He carefully studied the historiography of the issue, reexamined old evidence, gathered new information, and produced an authoritative study. Hackerd concluded:

Determining the beginning date for classes at the State Seminary of Indiana has challenged historians for decades. The use of newly located primary sources and a reevaluation of interpretations of early standard sources have resulted in the need to correct the official Indiana University timeline. Study of the biography of Baynard Rush Hall—the first teacher, newspaper notices issued by the State Seminary’s Board of Trustees, and Presbyterian church records substantiate April 4, 1825, as the date classes began at the State Seminary of Indiana in Bloomington.48

Thus, the mystery that dates to the early history of the institution found a satisfactory resolution. Ironically, the 1880s marked the invention of IU history as a literary genre and the creation of difficult problems with the university’s chronology.

3.7 Suppression of Historical Evidence

The two examples cited above were unintentional errors exacerbated by scarce records and faulty memories. Another, more serious case of distorting the university’s history involved David Banta suppressing a key fact as he recounted the story of the faculty war

of 1832, as presented in his 1892 Foundation Day address.49 As mentioned in Chapter 2, the conflict between Andrew Wylie and Baynard R. Hall began with an anonymous letter left for Hall at the end of the 1830–31 school year. The note eventually led to Hall’s resignation. In the spring of 1832, Professor Harney began having public conflicts with President Wylie, which led to his dismissal by the trustee board in the fall. Thus, at the close of Indiana College’s seventh year, the original faculty were gone, and the president and trustees had to recruit new teaching staff.

Banta learned the identity of the author of the anonymous note when he received a letter from Andrew Wylie Jr. in 1882 admitting authorship but chose to not reveal it in his Foundation Day address a decade later. Banta never revealed his reasons for suppressing Andrew Wylie Jr.’s name from his account of the faculty war, but one can surmise some possibilities. To begin with, both men were judges, with the expectation that their actions should exhibit probity, restraint, and wisdom. What would be gained by exposing a major institutional scandal that occurred sixty years earlier? Better to keep the secret within a small group of elder figures, perhaps.

The 1882 letter from Wylie to Banta was in the university archives for over a century, but the secret it contained was not revealed publicly until a biography of IU’s first professor, Baynard Rush Hall: His Story, was published in 2009 by Dixie Kline Richardson.50 Future historians of IU will need to take account of the fact that a student—the president’s son, no less—started a process that led to the separation of the original teaching staff from the institution. The episode should be renamed the war against the faculty

rather than the faculty war

possibly. Regardless, conflict between the administrative staff and instructional personnel were present from the start.

3.8 A Variation on the Theme

After the various efforts by Wylie, Banta, and Woodburn to construct a common foundation narrative for the university, a dozen years later another approach to IU history was tried. After rejecting an invitation to prepare an exhibit on Indiana University for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, President William Bryan explained: It was determined to prepare a book which should set forth in permanent form, for those interested, the salient features of the history and current status of the University. Out of this determination arose the present volume.

51 The book functioned along the line of a university viewbook, providing information for the interested public.

Edited by Samuel B. Harding, professor of European history, the book had three parts. The first, authored by William Rawles, professor of economic and social science, was a concise Historical Sketch,

laying out IU’s legislative history and organizational evolution. The works of the faculty trio were cited at least once, with Woodburn being quoted several times. The second part was a close study of the Development of the Course of Instruction

by Lewis Carson, assistant professor of philosophy. Based on surviving IU catalogs, his text documented the expansion of the curriculum from ancient classics to modern languages and the sciences. The final part was a cumulative bibliography of publications authored by present faculty members, past faculty members, alumni, and students. Librarian William A. Alexander supervised its compilation. Both Rawles and Carson eschewed promotional language and provided sober assessments of their respective subjects. Following the scholarly model pursued by Woodburn in his earlier study of IU history, their writing contrasted with Wylie’s focus on the academic community or Banta’s storytelling style.

The hybrid volume ritually invoked the past as a prologue to the university’s current aspirations. The number of pages for each section reveals something about the institution’s self-presentation. The first, containing a brief overview of its development for the last century, was 32 pages (9 percent). The second section, dealing with curriculum, was 160 pages (46 percent), with three-quarters of that (35 percent of the book) about departments as now constituted.

The final part, consisting of a bibliography of publications, was 153 pages (44 percent), subdivided into current faculty (28 pages), former faculty (26 pages), and alumni (98 pages). Curriculum and instruction, departmental organization and facilities, and intellectual production through scholarship are the key themes of the volume as the university presented itself to the wider world. History was a relatively minor theme used to understand the contemporary scene and to implicitly support the university’s aspirations for the future.

3.9 Perseveration: The Ritual Use of History

In 1914, when the first issue of the Indiana University Alumni Quarterly came out, Woodburn—remembering that the historical addresses of the late law school dean Banta had never been published in their entirety—arranged with the editor of the new periodical, fellow history professor Samuel Harding, to have them appear. Banta’s examination of The Indiana Seminary

appeared on page one, signaling the journal’s intent to cover all aspects of alumni experience, past and present. That 1889 address, given at the first Foundation Day, had first been published in Wylie’s historical catalog in 1890. The following five issues of the Alumni Quarterly published Banta’s subsequent addresses from 1890 to 1894, each for the first time, in a History of Indiana University

series.52 Later in 1914, Ivy Chamness began working as assistant editor of university publications and was soon drawn into editing the Alumni Quarterly as well, succeeding Harding.53

Between 1915 and 1917, Woodburn took up where Banta’s narrative ended and published a series of eight articles in the Alumni Quarterly. Under the general title Sketches from the University’s History,

he covered the 1850s at IU in detail. Consequential events included the employment of Professor Daniel Read, the death of President Andrew Wylie, and the 1854 campus fire. He included information about student life, the trustees, and the faculty and curriculum.54

In 1921, Chamness edited Indiana University, 1820–1920: Centennial Memorial Volume.55 The first one hundred pages collected all of Banta’s articles published in the Alumni Quarterly and republished them as History of Indiana University,

with the article titles serving as chapter headings. Part II included the addresses delivered at the Centennial Educational Conference held at IU in May 1920, under the title The American University: Today and Tomorrow.

The last part republished a lengthy account of the Centennial Commencement, written by Chamness for the July 1920 Alumni Quarterly.

In 1940, Woodburn finally published History of Indiana University, Volume I: 1820–1902, when he was eighty-four years old.56 The book was divided into two parts. The first six chapters were authored by Banta and reprinted, for the third time, the material published in 1914–15 and republished in 1921. The second part was authored by Woodburn and contained sixteen chapters, half reprinted from the 1915–17 Alumni Quarterly series and half new material. At the end, addenda were added that contained a miscellany of archival correspondence and notes that only became known when the manuscript was in page proofs.

Banta, who died in 1896, was the chief beneficiary of the emerging practice of perseveration in IU history publishing. He was the first out of the gate among the trio who invented IU history, delivering an oral address on the Indiana State Seminary of learning in 1889 at the first Foundation Day. His subsequent addresses were published many years after his death, in the first issues of the Alumni Quarterly in 1914–15. Then the six articles became part of the 1921 Centennial Memorial Volume. They were reprinted yet again in 1940 as the opening chapters of Woodburn’s History of Indiana University volume. Banta’s name has become indelibly associated with IU history.

This insistent repetition might have been justified because each new student generation should have an opportunity to become acquainted with the institution’s history, but that argument was never made explicitly. Closer to the truth was the implicit assumption that Banta’s narrative would function as the foundation story, and there was no need for further work on the early history of the university. In fact, many people were interested in the university’s story, but few had the interest and skill to write institutional history. Perseveration of Banta’s account through repeated republication was sustained for fifty years, from 1890 to 1940, a period of tremendous growth and change in the university. The impulse that animated Banta, Wylie, and Woodburn to invent IU history in the 1880s had faded, replaced by the ritual invocation of Banta’s stories of the early institution, including the creation of the state seminary, the coming of President Andrew Wylie, and the conflict that led to the departure of the original professor, Baynard Rush Hall.

3.10 Postwar Developments

In office since 1937, President Herman Wells had a deep appreciation for the past, filtered through his overriding concern for the improvement of the university. He inherited two institutional history projects that began under the previous administration of President Bryan. One was Woodburn’s History of Indiana University project, finished in 1940. The other was a project that resulted in a biographical directory, Trustees and Officers of Indiana University, 1820–1950, published in 1951.

In the early 1940s, the Wells administration authorized research for a second volume of History of Indiana University, to cover the thirty-five-year administration of President William Lowe Bryan from 1902 to 1937. Bryan, still very much alive, was pleased that the author was Burton Myers, the emeritus dean of the Bloomington medical school and a valued colleague. Myers was also tasked with bringing the long-delayed trustees book project to completion.

Spending the better part of a decade researching and writing until his death in 1951, Myers hewed close to the institutional records of the IU trustees and the president’s office. The result was a dry official chronicle more than an interpretive narrative. In 1952, History of Indiana University, Volume II: 1902–1937, The Bryan Administration was published. The massive volume also contained information reaching back to IU’s beginning in the nineteenth century. Whatever its literary deficiencies, the book remained an invaluable reference source and a permanent contribution to IU’s historiography.57

Through the 1950s and 1960s, Indiana University experienced great institutional growth in students and faculty, proliferation in academic programs and facilities, and a remarkable rise in national standing among research universities. After twenty-five years, the Wells administration ended in 1962, and the trustees bucked a seventy-five-year-old tradition of hiring from the inside and selected Elvis J. Stahr, a former secretary of the army, as president. Maintaining the university’s trajectory set by Bryan and Wells, Stahr oversaw the continued expansion of IU’s educational footprint around the state as well as gains in faculty research productivity and creative scholarship. As the university’s 150th anniversary approached in 1970, Stahr appointed Thomas D. Clark, University of Kentucky history professor (and one of Stahr’s former teachers), as visiting professor in 1967 to prepare a new narrative history of Indiana University.

Clark, an experienced regional historian, took on this task with gusto, examining voluminous primary sources, reading the existing historiography, and conducting numerous oral history interviews. Not since Woodburn’s 1891 dissertation research had a professional historian critically explored IU’s past—and there was a lot of material after 150 years. The most recent history volume—Myers’s (1952)—ended its coverage in 1937, prior to the Second World War and the tremendous postwar expansion.

Eventually Clark’s project expanded to three volumes of narrative history and a sourcebook of documents. The first volume of Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer, published during the IU sesquicentennial year, was the first retelling of the early history since Banta. The second volume, published in 1974, focused on the long presidency of Bryan and his consequential administration. The final volume came out in 1977, taking the story of IU from 1937 to 1968, covering the presidential administrations of Wells and Stahr. The volume garnered excellent reviews, both from the local press and from history of education scholars.58

The Clark volumes recast the history of Indiana University in a long narrative arc of 150 years. For the most part, it followed the foundation story first circulated in the 1880s when institutional history was mobilized as a university asset, adding a few details but not challenging the existing framework. Clark was kind to his predecessors. A key strength of Clark’s work was linking the deep and the more recent past into a single whole, although few readers had the stamina to read 1,500 pages over three volumes. Symbolically, the publication represented a turning point, when IU history, written by a professional historian recruited from beyond the institution, made its scholarly debut. It also inspired new work and gave it a richer context. To cite but one example: In 1980, Herman Wells published an autobiography, Being Lucky: Reflections and Reminiscences.59 The book was, in equal parts, an engaging autobiography, a manual of higher education management, and an artful spoof of his stellar career.

60 Readers of both volumes can get a considered view of how Wells transformed the university by perusing Clark’s history, and some flavor of Wells charm and personality that drove his relentless quest for educational improvement through his memoirs. Not since David Starr Jordan published Days of a Man: Being Memories of a Naturalist, Teacher, and a Minor Prophet of Democracy in 1922 had a former IU president engaged autobiographically.61

The Clark volumes remain an impressive scholarly monument as well as an inviting target for revisionist accounts. In the eighty years between the invention of IU history as a literary genre and the publication of Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer, accounts of IU’s past have played various roles for the institution and have contributed to the university’s identity and integrity. Since the 1970s, a comprehensive IU history has not been attempted, much less written. Perhaps two centuries are too long to cover in sufficient detail or the currents of fashion for microhistory run too swiftly. One can count on, however, institutional history playing a key role in the university’s public persona and contributing to the self-understanding of its diverse community.

The Society of the Alumni was organized in 1854 to provide moral and financial support in the wake of the College Building fire. See Janet Carter Shirley, The Indiana University Alumni Association: One Hundred and Fifty Years, 1854–2004 (Bloomington: Indiana University Alumni Association, 2004).↩︎

James A. Woodburn, History of Indiana University: Volume I, 1820–1902 (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1940), 332–35.↩︎

Theophilus A. Wylie, Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professor and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1890), 84.↩︎

David Starr Jordan, “Letter to Lemuel Moss,” October 7, 1883. IUA/C73/B1/F Jordan, David Starr.↩︎

Later, a picture was staged with the seven

Moss Killers,

displaying a wood drill, keyhole saw, and a hatchet on the wall behind.↩︎Minutes of the IU Board of Trustees, November 1884. Graydon tried to retract her letter of resignation the following month, but the trustees refused to consider it. Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 06 November 1884–11 November 1884” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 7, 1884), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-11-07.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 December 1884–19 December 1884” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 1884), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-12-16.↩︎

Days of a Man, Being Memories of a Naturalist, Teacher, and Minor Prophet of Democracy, vol. 1 (Yonkers-on-Hudson, NY: World Book Company, 1922), 295.↩︎

Jordan made this statement in his 1888 report as a trustee of Cornell University; quoted in W. T. Hewett, Cornell University: A History, vol. 1 (New York: University Publishing Society, 1905), p. 286.↩︎

“Diary Entry” (Indiana University Archives, September 6, 1885).↩︎

Days of a Man, Being Memories of a Naturalist, Teacher, and Minor Prophet of Democracy, 1:295.↩︎

Jordan, 1:295–96; Cf. James H. Capshew, “Indiana University as the ‘Mother of College Presidents’: Herman B Wells as Inheritor, Exemplar, and Agent” (Bloomington: IU Institute for Advanced Study, 2011), https://hdl.handle.net/2022/14123.↩︎

“The Indiana Seminary Charter of 1820,” Indiana Magazine of History 106 (2010): 359.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 June 1884–11 June 1884” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 7, 1884), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-06-04; cf. Burton Dorr Myers, Trustees and Officers of Indiana University 1820–1950, ed. Ivy L. Chamness and Burton D. Myers (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1951), 484–85.↩︎

Theophilus Wylie, “Diary Entry” (Indiana University Archives, June 28, 1857):

Baptized James Albert, sone [sic] of James & Martha Woodburn[.] Weather warm, summer like.

↩︎Wylie, Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professor and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887, 3.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 March 1884–25 March 1884” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 25, 1884), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-03-04.↩︎

Wylie first came in 1837, then spent two and a half years at Miami University in 1852–54, and then returned to IU.↩︎

Wylie, Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professor and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887, p. 14. Maxwell was not a member of the education subcommittee that wrote that section of the Indiana Constitution.↩︎

James Maxwell served as trustee board president from 1862 to 1865 during the Civil War.↩︎

“History of Indiana University I: The Seminary Period (1820–1828),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1914): 9.↩︎

Wylie, Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professor and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887.↩︎

“Letter to James Woodburn” (Indiana University Archives, February 9, 1889).↩︎

James Albert Woodburn, “Higher Education in Indiana,” ed. Herbert B. Adams, Bureau of Education, Circular of Information No. 1, 1891: Contributions to American Educational History (Washington: Government Publishing Office, 1891).↩︎

Woodburn, 77. Comma added.↩︎

Laying the Bottom Rail

was the title of chapter 3 in Thomas D. Clark, Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume I: The Early Years, 4 vols. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970), p. 25. McMains, “The Indiana Seminary Charter of 1820”, pp. 378–379.↩︎“History of Indiana University: IV. The ‘Faculty War’ of 1832,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 4 (1914): 370; see also Woodburn, History of Indiana University, 483, which repeats this interpretation uncritically.↩︎

Degrees awarded from Indiana College, 1830–37, and Indiana University, 1838–41:

- 1830: 4

- 1831: 4

- 1832: 5

- 1833: 3

- 1834: 4

- 1835: 4

- 1836: 8

- 1837: 10

- 1838: 10

- 1839: 7

- 1840: 5

- 1841: 5

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 15 February 1838” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 15, 1838), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1838-02-15.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 24 September 1838–27 September 1838” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 27, 1838), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1838-09-24.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 19 July 1841–24 July 1841” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, July 21, 1841), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1841-07-19.↩︎

In 1908, the portals were removed and integrated into the structure of the Rose Well House on the Dunn’s Woods campus.↩︎

See Jeremy L. Hackerd, “The Complex History of the Date Classes Began at the State Seminary of Indiana” (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, June 30, 2008). background report on the state historical marker ("State Seminary of Indiana" marker) for Seminary Square, Bloomington, Indiana State Historical Marker Program.↩︎

Wylie, Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professor and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887, 38–46, quote on p. 43.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 07 March 1987” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 7, 1987), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1987-03-07.↩︎

Indiana University, “IU Trustees Approve ‘Official Year’ of University’s First Classes” (Indiana University Archives, March 7, 1987). news release.↩︎

Herman B. Wells, “Letter to John Ryan” (Indiana University Archives, April 7, 1987).↩︎

The History of Mitchell Hall, 1885–1986 (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives, 1987).↩︎

“Letter to Dolores Lahrman” (Indiana University Archives, May 13, 1987).↩︎

Hackerd, “The Complex History of the Date Classes Began at the State Seminary of Indiana.” background report on the state historical marker ("State Seminary of Indiana" marker) for Seminary Square, Bloomington, Indiana State Historical Marker Program.↩︎

For a brief account of the secret, see also James H. Capshew, “New Light on an Old Story: The Secret of the Faculty War,” 200: The Bicentennial Magazine 1, no. 1 (2018): 6–8.↩︎

Samuel Bannister Harding, ed., Indiana University, 1820–1904 (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1904), vii.↩︎

Banta, “History of Indiana University I”; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: II: From Seminary to College (1826–1829),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1914): 142–65; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: III: The New Departure (1829–1833),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 3 (1914): 272–92; Banta, “History of Indiana University,” 1914; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: V: From College to University (1833–1838),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 1 (1915): 5–17; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: VI: Perils from Sectarian Controversies and the Constitutional Convention (1838–1850),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 2 (1915): 99–110.↩︎

James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History I: College Men and College Life about 1850,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2 (1915): 249–69; James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History II: College Men and College Life About 1850 (Continued),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2 (1915): 409–27; James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History III: Faculty and Curriculum about 1850,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 20–37; James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History IV: Daniel Read, Professor of Ancient Languages, 1843–1856,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 127–48; James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History V: Death of President Wylie: A Year of President Ryors and Election of Dr. Daily: Death and Services of Dr. David H. Maxwell,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 347–59; James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History VI: The Vincennes Suit and the Fire,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 489–500; James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History VII: Dark Days after the Fire: Courage in Adversity,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 4 (1917): 1–11; James A. Woodburn, “Sketches from the University’s History VIII: The Board of Trustees Sixty Years Ago; Student Reminiscences,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 4 (1917): 117–28.↩︎

Ivy L. Chamness, ed., Indiana University, 1820–1920: Centennial Memorial Volume (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1921).↩︎

Volume I reviews: Maynard Brichford, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984) 64, no. 3 (1971): 355–56, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40190803; Daniel W. Hollis, The Journal of American History 58, no. 1 (1971): 201–2, https://doi.org/10.2307/1890153; James Nolan, “Indiana University History,” Courier-Journal, January 17, 1971; Winton U. Solberg, Indiana Magazine of History 67, no. 3 (1971): 268–69, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27789750. Volume II reviews: J. David Hoeveler, “Higher Education in the Midwest: Community and Culture [Reviewed Volumes One and Two],” History of Education Quarterly 14, no. 3 (1974): 391–402, https://doi.org/10.2307/367940; Maynard Brichford, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984) 68, no. 3 (1975): 297–99, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40191173; Merle Curti, The American Historical Review 80, no. 3 (1975): 518–19, https://doi.org/10.2307/1850710; Patricia Albjerg Graham, Indiana Magazine of History 70, no. 2 (1974): 180–82, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27789965; Daniel W. Hollis, The Journal of American History 61, no. 2 (1974): 515–16, https://doi.org/10.2307/1904023; John Ed Pearce, “The Middle Years of Indiana University: A Review,” Courier-Journal, November 18, 1973. Volume III reviews: Merle Curti, The American Historical Review 83, no. 4 (1978): 1101, https://doi.org/10.2307/1867836; Daniel W. Hollis, The Journal of American History 65, no. 3 (1978): 836–37, https://doi.org/10.2307/1901512; William C. Ringenberg, History: Reviews of New Books 6 (1978): 148; Francis P. Weisenburger, Indiana Magazine of History 74, no. 4 (1978): 367–68, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27790338. Volume IV reviews: George W. Knepper, Indiana Magazine of History 75, no. 1 (1979): 95–96, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27790359.↩︎

Herman B Wells, Being Lucky: Reflections and Reminiscences (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980).↩︎

James H. Capshew, Herman B Wells: The Promise of the American University (Bloomington; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press; Indiana Historical Society Press, 2012), 332.↩︎

Jordan, Days of a Man, Being Memories of a Naturalist, Teacher, and Minor Prophet of Democracy.↩︎