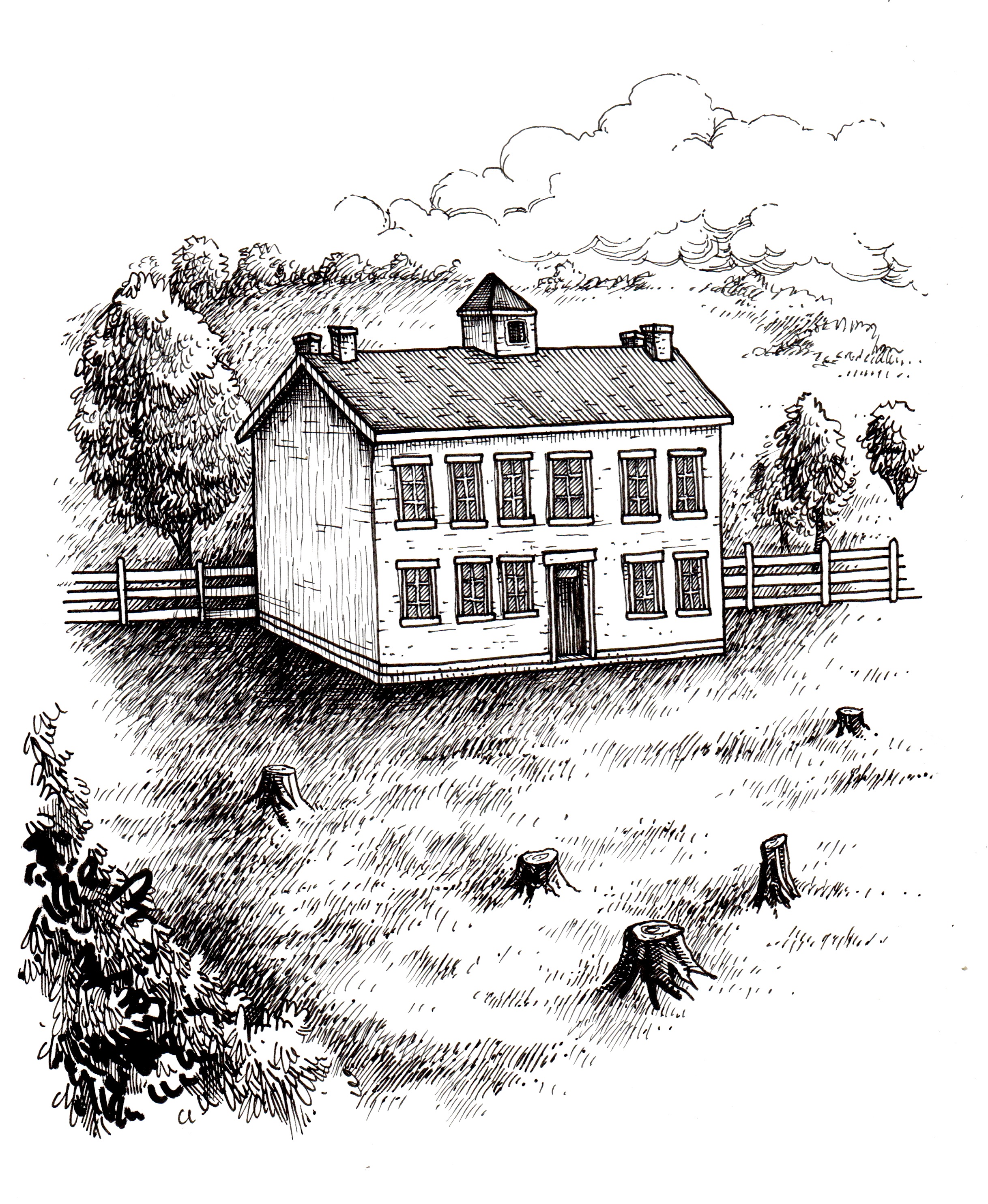

In 1835, President Wylie and his wife, Margaret, moved their large family into an imposing two-story brick house located near the college on a twenty-acre farmstead. One of the finest houses in the county, it was a marker of their social status. Meanwhile, the new College Building experienced prolonged delays in construction and was finally opened in 1836. The three-story brick structure was set on a foundation of limestone. Its design was inspired by a picture of a New England cotton factory [found] on a bolt of muslin in one of the stores of Bloomington

seen by one of the trustees. It housed the chapel, ample recitation rooms, and rooms for the Athenian and Philomathean student literary societies.

In 1838, with the campus as a going concern in the small town of 1,500, the college was legislatively transformed yet again, into Indiana University, with plans for schools of medicine and law to be established. That year, the Boarding-House was erected, incorporating the professor’s house in its structure. It provided accommodation for thirty to forty students, and residents could grow their own vegetables on the campus. (A small laboratory building was also planned but would not be erected until 1840.) Now the campus claimed a physical plant of four buildings—Seminary Building, professor’s house, Boarding-House, and College Building. The teaching staff remained small, however, reaching a low of three instructors in 1839. Chronically poor finances and lack of demand for higher education maintained the institutional status quo of basic subsistence.

The pace of change gained momentum in the 1850s. President Wylie died in 1851, at sixty-two, because of a woodchopping accident. He had led the infant institution for over two decades, ensuring its survival in the face of sectarian controversies and political pressures. His successors were men of the cloth, as the university was led by Protestant ministers until 1884.

The railroad came to Bloomington in 1853, revolutionizing transportation around the state and beyond. Coincidentally, the railroad tracks were placed along the west boundary of the campus and brought noise, smoke, and danger to a formerly peaceful locale.

Three years after Wylie died, disaster struck the physical plant. The main College Building was destroyed by fire in 1854, along with the library and administrative records. The small academic community organized the Society of the Alumni to mobilize support for university rebuilding, and the local government, as well as residents, contributed financially. The old Seminary Building and the small Laboratory Building were pressed into service for classroom space as trustees made plans for a new building.

The plan for the new University Building represented a departure from the past practice of the trustee board acting as building designers. Instead, the board hired a professional architect, the Irish-trained William Tinsley, who practiced in Cincinnati and Indianapolis. The edifice followed a Gothic style modified for college buildings, with brick as the main material, highlighted by handsome stonework made of locally sourced limestone on the windows and entry doors. The new University Building opened in 1855 and featured an image of the university seal, adopted in 1841, carved into the limestone.

By 1860–61, the faculty had grown to nine men, including the president. Debate over the Civil War roiled the IU campus as well as the town of Bloomington from 1860 to 1865. Some students enlisted in the Union Army; some fought for the Confederacy. Passionate arguments animated the two literary societies as they debated the causes of the war and whether secession was allowable under the US Constitution.

In 1869, the university lost its bid to become the recipient of a federal land grant to teach agriculture and engineering through the Morrill Act when the Indiana General Assembly accepted gifts from Tippecanoe County and John Purdue to establish an agricultural college in West Lafayette.

Curriculum expansion and increasing enrollments drove the trustees to the decision to build another major building on the campus—Science Hall—to accommodate a natural history museum, a chemical laboratory, the library, and the departments of philosophy, zoology, comparative anatomy, and law. The new science building, completed in 1873, was constructed of brick and trimmed in limestone. Indianapolis architect B. V. Enos designed the structure in collegiate Gothic style, to harmonize with the 1855 University Building. These two large academic halls, at right angles to each other, were the principal buildings on the campus site. The old Seminary Building and the Laboratory Building had been torn down in 1858, and the Boarding-House in 1864; some of the material found reuse in other structures in Bloomington.

Prompted by growing enrollments, the 1880s saw much change at Indiana University. Women students became more numerous after their initial admission in 1867, and a few African American students began to attend. Curricular reforms resulted in the expansion of courses of study: ancient classics, modern classics, and science. The faculty, in 1885, numbered twenty-four men.

In July 1883, a lightning strike ignited a blaze in Science Hall, and the building, with its library, museum collections, and university records, was destroyed and its contents a total loss. Despite the fact that the fire destroyed nearly half of the physical plant, the members of the university community were not as disheartened as they had been following the 1854 College Building fire. The university was larger and stronger, with an active alumni group, and the state had just started annual appropriations for university operations only months before. The board of trustees, headed by David Banta, a former circuit court judge, moved quickly to stabilize the situation and explore options. Some trustees thought it might be a suitable time to move the campus away from the railroad, and the board looked at several sites. The trustee board decided to buy twenty acres of the Dunn family farm on the eastern outskirts of town. That woodlot became the campus at Dunn’s Woods. The new Dunn’s Woods campus was ready in 1885, presided over by a new president, the former biology professor David Starr Jordan, who oversaw major changes in the curriculum that accompanied the move.

Indiana Student, April 1, 1898, 53.

Indiana Student, April 6, 1901, 12.

Arbutus, June 1906, 388–90.

Indiana Daily Student, November 15, 1999.

Bloomington Telephone 7, no. 46 (March 29, 1884): 1.

Bloomington: Indiana University Archives, n.d. IUA/C213/B30/F.

Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Vintage, 1996.

Adair, Douglass. Fame and the Founding Fathers: Essays by Douglass Adair. Edited by Trevor Colburn. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1974.

Addis, Alfred. “Latin Grammars.” The Literary and Theological Review 6, no. 21 (1839): 59–66.

Albert, Barb. “I.U. Group Launches Battle to Rescue Beloved Woods.” Indianapolis Star, February 12, 1982, 22.

“Alumni Council Meetings.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 6, no. 3 (July 1919): 392–94.

“Alumni Notes by Classes: 1906.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 24, no. 1 (1937): 74.

“Balls and Strikes: A Story.” Arbutus, 1899, 174–79.

Banta, D. D. A Historical Sketch of Johnson County, Indiana. Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co., 1881.

Banta, David D. “History of Indiana University I: The Seminary Period (1820–1828).” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1914): 3–24.

Banta, David D. “History of Indiana University: II: From Seminary to College (1826–1829).” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1914): 142–65.

Banta, David D. “History of Indiana University: III: The New Departure (1829–1833).” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 3 (1914): 272–92.

Banta, David D. “History of Indiana University: IV. The ‘Faculty War’ of 1832.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 4 (1914): 369–86.

Banta, David D. “History of Indiana University: V: From College to University (1833–1838).” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 1 (1915): 5–17.

Banta, David D. “History of Indiana University: VI: Perils from Sectarian Controversies and the Constitutional Convention (1838–1850).” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 2 (1915): 99–110.

Banta, David D. “Letter to James Woodburn.” Indiana University Archives, February 9, 1889.

Banta, David D. Indiana Student 9, no. 7 (May 1883): 166–67.

Benson, Olof. “Description of the Plan of Improvement of University Park.” Indiana University Archives/C77/B1, 1884.

Bernstein, Leonard. “Letter to David F. Parkhurst,” February 13, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.

Bischoff, Sue. “Nelson Pleased by Turnout, Originality.” Indiana Daily Student, n.d.

Blanchard, Charles, ed. Counties of Morgan, Monroe, and Brown, Indiana: Historical and Biographical. Chicago: F.A. Battey & Co., 1884.

Blanck, Jacob. Bibliography of American Literature. Vol. 3. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

Bracalente, Anita. “Indiana University’s Woodland Campus.” View 12 (2012): 25–27.

Brichford, Maynard.

Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984) 64, no. 3 (1971): 355–56.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40190803.

Brichford, Maynard.

Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984) 68, no. 3 (1975): 297–99.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40191173.

Brogan, Dan. “Plager’s Contempt on Compromise Out of Character for Law Profession.” Indiana Daily Student, February 19, 1982.

Brown, William M., and Michael W. Hamburger. “Organizing for Sustainability.” In Enhancing Sustainability Campuswide, edited by Bruce A. Jacobs and Jillian Kinzie, 83–96. New Directions for Student Services 137. Wiley, 2012.

Bryan, William. “Letter to George Kessler.” Indiana University Archives C286/B150/F Kessler, George, May 25, 1916.

Bryan, William Lowe. “Letter to James A. Woodburn.” Indiana University Archives, June 17, 1929. IUA/C83/B3/F Publications, Galleys, & Transcripts.

Bryan, William Lowe. “Letter to James A. Woodburn.” Indiana University Archives, November 17, 1934. IUA/C83/B3/F Publications, Galleys, & Transcripts.

Buley, R. Carlyle. The Old Northwest: Pioneer Period, 1815–1840. Vol. 2. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1950.

Bunnage, JoAnn C. “Barbara Shalucha and the Development of Hilltop Garden and Nature Center: The Cultivation of a Community Treasure,” 1999.

Burgess, Jo, ed.

Affectionately Yours: The Andrew Wylie Family Letters. I: 1828–1859, II: 1860–1918 vols. Bloomington: Wylie House Museum, 2011. Volume I:

https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/items/4323e65e-8053-4624-a19c-cec3c14205f0; Volume II:

https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/items/4c56273e-06d6-427e-a533-769e9cf5504e.

Busch, Jonah M. “The Protect Griffy Alliance and the Golf War: Collective Action at Its Finest,” April 28, 2000. seminar paper, Indiana University.

Caldwell, Lynton K. “Environment: A New Focus for Public Policy?” Public Administration Review 23 (1963): 132–39.

Caldwell, Lynton Keith. “Foreword: A Sense of Place.” In The Natural Heritage of Indiana, edited by Marion C. Jackson, xv–xvi. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Campbell, Matthew. “Letter to David Banta.” Indiana University Archives/C112/B1, December 25, 1882.

“Campus Improvements Due to Prof. Mottier.” Indiana Daily Student, February 5, 1904, 1.

Capshew, James H. Herman B Wells: The Promise of the American University. Bloomington; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press; Indiana Historical Society Press, 2012.

Capshew, James H.

“Indiana University as the ‘Mother of College Presidents’: Herman B Wells as Inheritor, Exemplar, and Agent.” Bloomington: IU Institute for Advanced Study, 2011.

https://hdl.handle.net/2022/14123.

Capshew, James H. “IU Country Club?” Herald-Times, September 4, 1999.

Capshew, James H. “Memo University Seal.” Reference file: University Seal. Indiana University Archives, March 1, 2019.

Capshew, James H. “New Light on an Old Story: The Secret of the Faculty War.” 200: The Bicentennial Magazine 1, no. 1 (2018): 6–8.

Capshew, James H. “Nicklaus Course Raises Questions.” Herald-Times, no. editorial (September 8, 1999).

Capshew, James H.

“The Campus as a Pedagogical Agent: Herman Wells, Cultural Entrepreneurship, and the Benton Murals.” Indiana Magazine of History 105, no. 2 (2009): 179–97.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27792978.

Carleton, Emma. “About the New Purchase.” Indianapolis News, May 16, 1902.

Carmichael, Hoagy. The Stardust Road. 1946. Reprint, New York: Greenwood Press, 1969.

Carmichael, Hoagy, and Stephen Longstreet. Sometimes i Wonder: The Story of Hoagy Carmichael. New York: Farrer, Straus; Giroux, 1965.

Carr, Edward Hallett. What Is History? New York: Knopf, 1961.

Cassidy, Frederic G., ed. Dictionary of American Regional English. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985.

Center on Education Policy.

“Public Schools and the Original Federal Land Grant Program: A Background Paper from the Center on Education Policy.” Washington, 2011-04.

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED518388.

Chamness, Ivy. “Letter to Alumni Council.” Indiana University Archives, March 22, 1919. IUA/C286/B54.

Chamness, Ivy. “Letter to Herman B Wells.” Indiana University Archives, 1938. IUA/C213/B118.

Chamness, Ivy. “Letter to James A. Woodburn.” Indiana University Archives, November 30, 1940. IUA/C83/B4/F Testimonial Banquet/Correspondence.

Chamness, Ivy. “Letter to Mrs. C. J. Sembower.” Indiana University Archives, June 3, 1935. IUA/C84/B1/F Edited Manuscripts-Alumni Quarterly.

Chamness, Ivy. “Letter to William Lowe Bryan.” Indiana University Archives, June 18, 1919. IUA/C286/B54.

Chamness, Ivy. “Letter to William Lowe Bryan.” Indiana University Archives, May 11, 1920. IUA/C286/B54.

Chamness, Ivy L. “Another College President.” IU Alumni Quarterly 10 (1923): 512.

Chamness, Ivy L. “Another College President.” IU Alumni Quarterly 25 (1938): 59.

Chamness, Ivy L., ed. Indiana University, 1820–1920: Centennial Memorial Volume. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1921.

Chamness, Ivy L. “Indiana University in Earlier Days: I. As Reflected in Commencement and Exhibition Programs.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 16, no. 1 (1929): 33–45.

Chamness, Ivy L. “Indiana University in Earlier Days: II. As Reflected in Early Issues of the Indiana Student.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 16, no. 2 (1929): 199–221.

Chamness, Ivy L. “Indiana University—Mother of College Presidents.” Educational Issues 2, no. 8 (1921): 28–29.

Chamness, Ivy L. “Indiana University—Mother of College Presidents.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 9 (1922): 46–49.

Chamness, Ivy L. “IUA/C84/B1/f Edited Manuscripts-Myers.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives, n.d.

Chamness, Ivy L. “More College Presidents.” IU Alumni Quarterly 10 (1923): 334.

Chamness, Ivy L. “The First 125 Years.” Indiana Alumni Magazine 7, no. 9 (1945): 11–14.

Chamness, Ivy Leone. “A Study of Editorial Matters in the Catalogs of the Members of the National Association of State Universities.” Indiana University, 1928. Master’s thesis, Indiana University.

Chamness, Ivy Leone. “Alumni Notes by Classes.” Edited by Ivy Leone Chamness. Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 2 (April 1915): 207.

Chamness, Ivy Leone. “Indiana University in Earlier Days: III. As Reflected in the Issues of the Indiana Student in the Nineties.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 17, no. 1 (1930): 22–38.

Chamness, Ivy Leone. “Indiana University in Earlier Days: IV. As Reflected in Issues of the Indiana Student in the Nineties.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1931): 156–71.

Chamness, Ivy Leone. “Indiana University in Earlier Days: V. As Reflected in Historical Material Recently Given to the Institution.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 18, no. 1 (1931): 16–29.

Chamness, Ivy Leone. “Indiana University in Earlier Days: VI. As Reflected in Official Publications.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 20, no. 2 (1933): 159–68.

Chamness, Ivy Leone. “Indiana University in Earlier Days: VII. As Reflected in Official Publications.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 21, no. 2 (1934): 34–47.

Chapman, M. Perry. American Places: In Search of the Twenty-First Century Campus. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006.

“Charles H. Hays.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 24 (1937): 511–12.

“Charles H. Hays.” Indiana Alumni Magazine 19, no. 7 (1957): 1.

Chaudemanche, Diane, and Elaine Herold, eds.

Andrew Wylie: A Bibliography, 2000.

http://hdl.handle.net/2022/20329.

Clapacs, J. Terry. Indiana University Bloomington: America’s Legacy Campus. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017.

Clark, Thomas D. Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer. 4 vols. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970/1977.

Clark, Thomas D. Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume I: The Early Years. 4 vols. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970.

Clark, Thomas D. Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume II: In Mid-Passage. 4 vols. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973.

Clark, Thomas D. Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume III: Years of Fulfillment. 4 vols. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Bernstein Note Indicates Support for ‘Save the Woods’.” Indiana Daily Student, February 19, 1982.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Law Addition Sparks Dispute over Woods.” Indiana Daily Student, January 19, 1982.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Law School Addition Plans to Be Resubmitted.” Indiana Daily Student, 1982-02-11.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Law School Expansion Inquiry Buried.” Indiana Daily Student, March 31, 1982.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Law School Expansion May Incapacitate Observatory.” Indiana Daily Student, January 21, 1982, 1.

Cokinos, Christopher. “New Addition Plan Would Save Woods.” Indiana Daily Student, April 2, 1982.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Ryan Requests Look at Options for Law School.” Indiana Daily Student, February 25, 1982.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Save the Woods Group Organizing to Protect Old Crescent.” Indiana Daily Student, February 10, 1982, 3.

Cokinos, Christopher. “State to Determine If Law Applies to IU Expansion.” Indiana Daily Student, March 12, 1982.

Cokinos, Christopher. “Wells: University to Develop Campus Natural-Areas Policy.” Indiana Daily Student, April 30, 1982, 2.

Cokinos, Christopher, and Barbara Toman. “Trustees to Hear Law Expansion Opposition.” Indiana Daily Student, March 5, 1982.

Collins, Dottie. “Conversations about the Bloomington Campus: It Isn’t Easy Being Green (but Planning Ahead Helps).” The College 16, no. 2 (1992): 8–11.

“Commencement, 1938.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 25, no. 3 (1938): 298–337.

Conway, Thomas G. “Finding America’s History.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 97, no. 2 (2004): 92–106.

Council for Environmental Stewardship. “Annual Report,” 1998–1999.

Council for Environmental Stewardship. “Annual Report,” 2001–2002.

Council for Environmental Stewardship. “Annual Report,” 2002–2003.

Counts, Will, James H. Madison, and Scott Russell Sanders. Bloomington Past and Present. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

Cravens, J. W. “History of University Land Purchases.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 2 (1915): 156–59.

Cravens, John W. “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University: I. The Old Seminary Building.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 9, no. 1 (1922): 1–11.

Cravens, John W. “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University: II: Six of the Buildings on the Old Campus.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 9, no. 2 (1922): 156–64.

Cravens, John W. “Buildings on the Old and New Campuses of Indiana University: III. Buildings on the New Campus and Elsewhere in Monroe County.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1922): 303–20.

Cravens, John W. “The Trustees of Indiana University.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 14 (1927): 465–83.

Cumings, E. R.

“The Geological Conditions of Municipal Water Supply in the Driftless Area of Southern Indiana.” Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 21 (1911): 111–46.

https://journals.indianapolis.iu.edu/index.php/ias/article/view/14025.

Curti, Merle.

The American Historical Review 80, no. 3 (1975): 518–19.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1850710.

Curti, Merle.

The American Historical Review 83, no. 4 (1978): 1101.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1867836.

Cusack, Nick. “First IU Sustainability Director Named.” Indiana Daily Student, February 19, 2009.

Day, Harry G. The Development of Chemistry at Indiana University, 1829–1991. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1992.

“Death of Eugene Kerr.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 11, no. 4 (1924): 543–44.

“Discover Ruins of Seminary Building.” Indiana Daily Student, January 18, 1922, 3.

Dreiser, Theodore. A Hoosier Holiday. New York: John Lane Company, 1916.

“Drinking Fountain at I.U.” Indiana Daily Student, March 9, 1912.

Edmondson, Frank K. “Daniel Kirkwood—‘Dean of American Astronomers’.” Mercury 29, no. 3 (2000): 27–33.

Ehman, Lee. “The Dunn Name, but Not the Spirit.” Monroe County Historian 3 (August 2010): 10–11.

Ehrmann, Bess V. The Missing Chapter in the Life of Abraham Lincoln. Chicago: Walter M. Hill, 1938.

Ellis, Edith Hennel. “The Trees on the I.U. Campus.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 16, no. 3 (1929): 328–31.

“Environmental Action Day April 22 Schedule of Activities.” Indiana Daily Student, April 22, 1970.

Environmental Law Society. “Position Statement on the Proposed Law School Addition,” February 24, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.

Erekson, Keith A. Everybody’s History: Indiana’s Lincoln Inquiry and the Quest to Reclaim a President’s Past. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

Esarey, Logan. History of Indiana. Indianapolis: W. K. Stewart Co., 1915.

“Faculty Necrology.” Reference file, Indiana University Archives, n.d.

Fancher, John. “IU Law School Addition Will Not Harm Trees.” Herald-Telephone, March 7, 1982, 1.

Fancher, John. “IU Trustees OK Law School Addition.” Herald-Times 15, no. 15 (December 6, 1981): 1, 8.

Fancher, John. “Law School Addition OK’d.” Herald-Telephone, April 4, 1982.

Fancher, John. “Law School Addition Still Up in the Air.” Herald-Telephone, March 6, 1982, 1.

Fancher, John. “Law School Plan That Saves Woods Moves Ahead.” Herald-Telephone, April 3, 1982.

Ferguson, Jenny. “Working to Save the Woods, Ryan Makes His Feeling Heard.” Indiana Daily Student, March 1, 1982. For the Opinion Board.

Ferries, Ken, and Linda Herman. “Woodstock, 4-H Flavor I.U. Environmental Fair.” Indiana Daily Student, April 23, 1970.

Field, Oliver P. Political Science at Indiana University, 1829–1951. Bloomington: Bureau of Government Research, Department of Government, Indiana University, 1952.

“Football Men Wore Mustaches When He Came to University.” Indiana Daily Student 50, no. 56 (December 3, 1921): 2.

Franklin, J. A. “Letter to Thomas D. Brock.” Indiana University Archives/C268/B13/F Committee, Natural Areas, July 21, 1966.

Frey, Juliet, ed. “Islands of Green and Serenity: The Courtyards of Indiana University.” Bloomington: Indiana University Publications, 1987.

Fuchs, Ralph F. “Letter to the Editor.” Herald-Telephone, March 2, 1982, 8.

Gabbay, Sue Davis. “Letter to Brad Cook.” Indiana University Archives/Reference file: B+G Sunken Gardens, March 2013.

Gaines, Thomas A. The Campus as a Work of Art. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1991.

Garton, Daisy. “Letter to Trustees of Indiana University, President Myles Brand, and Members of the Higher Education Commission,” January 12, 2000.

Goodwin, Clarence L. “The Indiana Student and Student Life in the Early Eighties.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 17, no. 1 (1930): 146–58.

Graham, Patricia Albjerg.

Indiana Magazine of History 70, no. 2 (1974): 180–82.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27789965.

Gray, Donald J., ed. The Department of English at Indiana University Bloomington, 1868–1970. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1973.

Gray, Donald J. “The IU Necrologist: Duties and Procedures,” circa 2017.

“Greening the IMU: Eco-Charrette Report.” Bloomington: Indiana University, February 23, 2010.

Hackerd, Jeremy L. “The Complex History of the Date Classes Began at the State Seminary of Indiana.” Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, June 30, 2008. background report on the state historical marker ("State Seminary of Indiana" marker) for Seminary Square, Bloomington, Indiana State Historical Marker Program.

Hall, Baynard Rush. Exercises, Analytical and Synthetical; Arranged for the New and Compendious Latin Grammar. Bedford: Harrison Hall, 1836.

Hall, Baynard Rush. Frank Freeman’s Barber Shop. New York: Scribner, 1852.

Hall, Baynard Rush. “Letter to John Nunemacher,” May 13, 1855.

Hall, Baynard Rush. Teaching, a Science: The Teacher an Artist. New York: Baker; Scribner, 1848.

Hall, Baynard Rush. The New Purchase; or, Early Years in the Far West. 2nd ed. New Albany, IN: Jno. R. Nunemacher, 1855.

Hall, Baynard Rush (Robert Carlton, pseud.). The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West. Edited by J. A. Woodburn. 1843. Reprint, Princeton University Press, 1916.

Hall, Baynard Rush, Donald F. Carmony, and Herman J. Viola. “The New Purchase: Or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West.” Indiana Magazine of History 62, no. 2 (1966): 101–20.

Hamburger, Michael. “Editorial.” Herald-Times, November 30, 1999.

Hamilton, Lee. “The Popularity of the Environmental Issue.” Indiana University Archives/Lee H. Hamilton Congressional Papers, 1965–1998/MPP2B142/Folder 18, Speech Book 16, Q., April 22, 1970.

Harding, Samuel Bannister, ed. Indiana University, 1820–1904. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1904.

Harrison, Robert Pogue. Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Hart, James D. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Herold, Don. College Humor, November 1929, 130–31.

“Hershey, Mrs. Amos Shartle.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives, n.d. IUA/C213/B268/F.

Hewett, W. T. Cornell University: A History. Vol. 1. New York: University Publishing Society, 1905.

Hight, Kate M. “Reminiscences.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 24, no. 4 (1937): 455–60.

Hoeveler, J. David.

“Higher Education in the Midwest: Community and Culture [Reviewed Volumes One and Two].” History of Education Quarterly 14, no. 3 (1974): 391–402.

https://doi.org/10.2307/367940.

Hollis, Daniel W.

The Journal of American History 58, no. 1 (1971): 201–2.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1890153.

Hollis, Daniel W.

The Journal of American History 65, no. 3 (1978): 836–37.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1901512.

Hollis, Daniel W.

The Journal of American History 61, no. 2 (1974): 515–16.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1904023.

Hooker, Lisa. “RHA Votes to Ask the Trustees to ‘Save the Trees’.” Indiana Daily Student, February 18, 1982.

Horn, David. “Golf Course Opponents Jam Benefit Concert.” Herald-Times, January 17, 2000.

Hubach, Robert R. “Nineteenth-Century Literary Visitors to the Hoosier State: A Chapter in American Cultural History.” Indiana Magazine of History 45 (1949): 39–50.

Hunt, Ralph. “Enlightening Situation? Well House Wattage Encourages Conversation Rather Than Action.” Indiana Daily Student, November 1, 1961.

“Ideas Concerning Campus Plans Change Considerably with Time.” Indiana Daily Student 41, no. 98 (February 11, 1916): 3.

Iglehart, John E. “Correspondence Between Lincoln Historians and This Society.” In Proceedings of the Southwestern Indiana Historical Society, Vol. 63–88. 18. Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1923.

“In Memoriam: William A. Rawles, ’84, Robert A. Ogg, ’72, William T. Patten, ’93; and Necrology List.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 23, no. 3 (1936): 303–13.

“Inaugurating What Is Expected to Be an Annual Custom.” Indianapolis Star, May 5, 1939, 17. Photo caption.

Indiana University. “Annual Catalogue of the Indiana University for the Academical Year 1885–86.” Bloomington: Indiana University, 1886.

Indiana University. “IU Trustees Approve ‘Official Year’ of University’s First Classes.” Indiana University Archives, March 7, 1987. news release.

Indiana University Archives. “Finding Aid, Collection 286, Box 54.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, n.d. IUA/C286/B54.

Indiana University Archives. “Reference File: Class Gifts.” Bloomington: Indiana University; Unpublished archival material, n.d.

Indiana University Bloomington Faculty Council.

“Indiana University Bloomington Faculty Council Minutes, 02 February 1982.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 2, 1982.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/bfc/1982-02-02.

Indiana University Bloomington Faculty Council.

“Indiana University Bloomington Faculty Council Minutes, 07 September 2010.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 7, 2010.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/bfc/2010-09-07.

Indiana University Bloomington Faculty Council.

“Ndiana University Bloomington Faculty Council Minutes, 06 February 2018.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 6, 2018.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/bfc/2018-02-06.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 01 December 1952.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 1, 1952.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1952-12-01.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 01 June 1888–07 June 1888.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 2, 1888.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1888-06-01.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 01 November 1996.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 1, 1996.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1996-11-01.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 01 October 1948–02 October 1948.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, October 1, 1948.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1948-10-01.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 02 February 1980.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 2, 1980.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1980-02-02.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 April 1982.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, April 3, 1982.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1982-04-03.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 June 1885–10 June 1885.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 10, 1885.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1885-06-03.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 March 1981.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 7, 1980.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1981-03-07.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 November 1938–04 November 1938.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 3, 1938.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1938-11-03.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 03 September 1902–15 September 1902.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 6, 1902.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1902-09-03.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 April 1935.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, April 4, 1935.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1935-04-04.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 June 1884–11 June 1884.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 7, 1884.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-06-04.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 March 1884–25 March 1884.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 25, 1884.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-03-04.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 March 1935.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 4, 1935.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1935-03-04.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 May 2001.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 4, 2001.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2001-05-04.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 04 November 1897–06 November 1897.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 5, 1897.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1897-11-04.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 05 December 1981.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 5, 1980.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1981-12-05.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 05 December 2014.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 5, 2014.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2014-12-05.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 05 November 1885–11 November 1885.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 11, 1885.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1885-11-05.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 05 October 2017–06 October 2017.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, October 5, 2019.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2017-10-05.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 06 March 1982.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 6, 1982.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1982-03-06.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 06 November 1884–11 November 1884.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 7, 1884.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-11-07.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 07 December 2012.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 7, 2012.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2012-12-07.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 07 March 1987.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 7, 1987.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1987-03-07.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 07 May 2010.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 7, 2010.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2010-05-07.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 April 1983.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, April 9, 1983.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1983-04-09.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 August 1937.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, August 9, 1937.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1937-08-09.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 June 2006.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 9, 2006.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2006-06-09.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 May 1980.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 9, 1980.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1980-05-09.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 10 October 1941–11 October 1941.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, October 10, 1941.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1941-10-10.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 11 June 1891–17 June 1891.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 16, 1891.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1891-06-11.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 12 June 1947–14 June 1947.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 12–14, 1947.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1947-06-13.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 12 June 1953.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 12, 1953.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1953-06-12.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 12 September 1947–13 September 1947.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 12, 1947.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1947-09-12.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 13 March 1925–14 March 1925.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 14, 1925.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1925-03-13.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 14 August 2009.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, August 14, 2009.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2009-08-14.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 14 July 1961–15 July 1961.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, July 14, 1961.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1961-07-14.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 14 June 2019.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 14, 2019.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2019-06-14.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 15 August 2008.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, August 15, 2008.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2008-08-15.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 15 February 1838.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 15, 1838.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1838-02-15.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 15 September 2000.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 15, 2000.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2000-09-15.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 December 1884–19 December 1884.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 1884.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1884-12-16.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 June 1904–22 June 1904.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 22, 1904.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1904-06-16.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 November 1898–18 November 1898.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 18, 1898.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1898-11-16.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 November 1951.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 16, 1951.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1951-11-16.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 17 February 1950.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, February 17, 1950.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1950-02-17.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 17 March 1950.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 17, 1950.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1950-03-17.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 19 December 1943.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 19, 1943.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1943-12-19.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 19 January 1950.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, January 19, 1950.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1950-01-19.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 19 July 1841–24 July 1841.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, July 21, 1841.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1841-07-19.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 19 June 1908–23 June 1908.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 22, 1908.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1908-06-19.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 19 May 1950.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 19, 1950.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1950-05-19.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 20 January 1961–21 January 1961.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, January 20–21, 1961.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1961-01-20.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 20 March 1894–23 March 1894.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 22, 1894.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1894-03-20.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 21 October 1949–22 October 1949.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, October 21, 1949.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1949-10-21.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 22 June 1942–23 June 1942.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 23, 1942.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1942-06-22.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 22 November 1937–23 November 1937.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 23, 1937.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1937-11-22.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 22 September 1947.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 22, 1947.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1947-09-22.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 22 September 1972.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 22, 1972.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1972-09-22.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 23 March 1899–25 March 18997.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 25, 1899.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1899-03-23.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 24 March 1902–25 March 1902.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 25, 1902.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1902-03-24.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 24 September 1838–27 September 1838.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 27, 1838.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1838-09-24.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 24 September 1994.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 24, 1994.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1994-09-24.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 25 March 1940–26 March 1940.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 25, 1940.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1940-03-25.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 25 March 1940–26 March 1940.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, March 26, 1940.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1940-03-25.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 25 September 1941–27 September 1941.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 27, 1941.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1941-09-25.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 27 June 1997.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, July 27, 1997.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1997-06-27.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 28 January 1944–30 January 1944.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, January 28, 1944.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1944-01-28.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 30 June 1947.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 30, 1947.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1947-06-30.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 30 May 1941–02 June 1941.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 31, 1941.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1941-05-30.

Indiana University Board of Trustees.

“Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 31 May 1963–03 June 1963.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 31, 1963.

https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1963-05-31.

“I.U. Founding to Be Observed by Alumni Throughout the World.” Indianapolis News, May 2, 1939, 13.

IU Office of Sustainability. “Office of Sustainability 2020 Vision,” 2010.

IU Task Force on Campus Sustainability. “Campus Sustainability Report.” Bloomington: Indiana University, January 7, 2008.

“IUA/C239/B3 All-University Committee on Names.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives, n.d.

“Ivy Chamness to Edit Quarterly.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 8 (1921): 331–32.

Jacobs, Bruce A., and Jillian Kinzie. “Editors’ Notes.” In Enhancing Sustainability Campuswide, edited by Bruce A. Jacobs and Jillian Kinzie, 1–6. New Directions for Student Services 137. Wiley, 2012.

Jordan, David Starr. Days of a Man, Being Memories of a Naturalist, Teacher, and Minor Prophet of Democracy. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Yonkers-on-Hudson, NY: World Book Company, 1922.

Jordan, David Starr. “Letter to Lemuel Moss,” October 7, 1883. IUA/C73/B1/F Jordan, David Starr.

Keith, B. D., B. T. Hill, and M. R. Johnson.

“Indiana University Campus Limestone Tour.” Digital Information. Indiana Geological Survey, 2015.

https://legacy.igws.indiana.edu/bookstore/details.cfm?Pub_Num=DI02.

Keith, Brian D. “Follow the Limestone: A Walking Tour of Indiana University.” 2009. Reprint, Bloomington: Originally published June 2009 by Indiana Geological Survey; Bloomington/Monroe County Convention; Visitors Bureau; republished July 2013 by Indiana Geological Survey; Visit Bloomington; current edition published July 2018 by Indiana Geological; Water Survey; Visit Bloomington, July 2018.

Keith Buckley, Linda Fariss, Derek F. DiMatteo, and Colleen Pauwels, eds. Trustees and Officers of Indiana University, Volume III: 1982–2018. Bloomington: Indiana University, 2019.

Knepper, George W.

Indiana Magazine of History 75, no. 1 (1979): 95–96.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27790359.

Krause, Carrol. Showers Brothers Furniture Company: The Shared Fortunes of a Family, a City, and a University. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Lahrman, Dolores M., and Delbert C. Miller. The History of Mitchell Hall, 1885–1986. Bloomington: Indiana University Archives, 1987.

Lesnick, Gavin.

“Campus Icon Retains History, Myth from 1868.” Indiana Daily Student, September 13, 2005.

https://www.idsnews.com/article/2005/09/campus-icon-retains-history-myth-from-1868.

Levell, Frank H. “Report of the Alumni Secretary.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 8 (1921): 323.

Levine, Arthur.

“Higher Education Becomes a Mature Industry.” About Campus: Enriching the Student Learning Experience 2, no. 3 (1997): 31–32.

https://doi.org/10.1177/108648229700200.

Levine, Arthur. “How the Academic Profession Is Changing.” Daedalus 126, no. 4 (1997): 1–20.

“‘Local’ Column.” Indiana Student, May 26, 1896, 29.

Louis, Kenneth Gros. “Remarks at the Sample Gates and Plaza Dedication.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives, June 13, 1987. John Ryan Speeches, Indiana University Archives/C45.

Lyon, Robert E. “The History of Chemistry at Indiana University, 1829–1931.” Indiana University News-Letter 19, no. 3 (March 1931).

Madison, James H. Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; Indiana Historical Society Press, 2014.

Madison, James H. Indiana University Department of History: Past to Present. Bloomington: Indiana University Department of History, 2010.

McCaslin, William, and D. D. Banta. History of Johnson County, Indiana. Chicago: Brant & Fuller, 1888.

McLaughlin, H. Roll. “HABS in Indiana, 1955–1982: Recollections.” In Historic American Buildings Survey in Indiana, edited by T. M. Slade, 13–20. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983.

McMains, Howard F. “The Indiana Seminary Charter of 1820.” Indiana Magazine of History 106 (2010): 356–80.

“Meeting in Woodburn Room, June 4, 1936,” June 4, 1936. Folder: Publications, Galleys & Transcripts, IUA/C83/B3/F, Indiana University Archives.

Merriman, Jerry. “How Should We Grow?” Herald-Times, November 10, 1999. letter to the editor.

Morrison, Sarah Parke. “Some Sidelights of Fifty Years Ago.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 6, no. 3 (July 1919): 529–35.

Mottier, David. “Letter to Joseph Pierce.” Indiana University Archives C174/B31/F Mottier, David, February 13, 1896.

Mottier, David. “Letter to William Bryan.” Indiana University Archives C174/B31/F Mottier, David, November 5, 1902.

Mottier, David, and Ulysses S. Hanna. “Suggestions on the Improvement of the East Campus.” Indiana University Archives C174/B31/F Mottier, David, November 10, 1913. report to IU Board of Trustees.

Murray, Agnes M. “Early Literary Developments in Indiana.” Indiana Magazine of History 36 (1940): 327–33.

Myers, Burton D. “Letter to Herman B Wells.” Indiana University Archives, April 1, 1941. IUA/C213/B404/F Myers, Dean B. D.

Myers, Burton Dorr. History of Indiana University: Volume II, 1902–1937, The Bryan Administration. Edited by Burton D. Myers and Ivy L. Chamness. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1952.

Myers, Burton Dorr. The History of Medical Education in Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1956.

Myers, Burton Dorr. Trustees and Officers of Indiana University 1820–1950. Edited by Ivy L. Chamness and Burton D. Myers. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1951.

Nave, Erin, and Kara Saige. “Golf Course Cancelled.” Indiana Daily Student, January 18, 2000.

Nolan, James. “Indiana University History.” Courier-Journal, January 17, 1971.

“Obituary: Baynard Rust [sic] Hall.” New York Times, January 27, 1863, 5.

Office of the Bicentennial.

“Indiana University Bicentennial Final Report.” Bloomington: Indiana University, 2020.

https://wayback.archive-it.org/219/20240413230003/https://200.iu.edu/doc/IU-bicentennial-final.pdf.

Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot. “Letter to Joseph Swain.” Indiana University Archives C174/B32/F Olmsted, Olmsted,; Eliot—Campus Plan 1896, December 8, 1896.

Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Parkhurst, David F. “Letter to Kenneth Gros Louis,” January 18, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.

Parkhurst, David F. “Letter to Leonard Bernstein,” February 7, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.

Patton, John B. “Location to the Natural Areas Committee,” June 30, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files, University Archives, Indiana University.

Pearce, John Ed. “The Middle Years of Indiana University: A Review.” Courier-Journal, November 18, 1973.

Pering, Cornelius. “The Pering Letters of 1833.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly, no. 20 (1933): 409–28.

Plager, Sheldon J. “Letter to Alumni and Friends of the University and the Law School Community,” April 8, 1982.

Plager, Sheldon J. “The Woods and the Law School Institution Addition,” February 1, 1982. Memo to Law School Student Body and Staff. David F. Parkhurst files, University Archives, Indiana University.

Pope, Alexander. An Epistle to the Right Honourable Richard Earl of Burlington. London: L. Gilliver, 1731.

Preservation Development Inc. “Wylie House Historic Structure Report.” Bloomington, 2001.

“Professors Take Divergent Views on Building Site.” Indiana Daily Student, March 28, 1935, 1, 3.

“Program for the Rededication Ceremony for Indiana University’s Owen Hall and Wylie Hall, October 18, 1985.” Bloomington: University Printing Services, 1985.

Pyle, Ernie. “It’s in the Air.” Indiana Daily Student, September 5, 1922, 4.

Quinn, Roy. “Letter to Herman Wells.” Indiana University Archives, May 16, 1938. IUA/C213/B455.

Relph, Edward. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion Limited, 1976.

Reynolds, Heather, Eduardo Brondizio, and Jennifer Robinson, eds. Teaching Environmental Literacy: Across Campus and Across the Curriculum. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Richardson, Dixie Kline. Baynard Rush Hall: His Story. Indianapolis: Dixie Kline Richardson, 2009.

Riddle, Ward G. “Letter to Burton D. Myers.” Indiana University Archives, April 21, 1942. IUA/C213/B404.

Ringenberg, William C. History: Reviews of New Books 6 (1978): 148.

Roberts, Sam. “Leon G. Billings, Architect of Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, Dies at 78.” New York Times, November 17, 2016.

Roehr, Eleanor. Trustees and Officers of Indiana University, 1950 to 1982. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1983.

Roosevelt, Theodore. “Straightout Americanism.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 5, no. 3 (July 1918): 295–307.

Ross, John M. “Letter to Herman B Wells,” April 27, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.

Rothblatt, Sheldon. “A Note on the ‘Integrity’ of the University.” In Aurora Torealis: Studies in the History of Science and Ideas in Honor of Tore Frängsmyr, edited by Marco Beretta, Karl Grandin, and Svante Lindqvist, 277–98. Sagamore Beach, MA: Science History Publications, 2008.

Roznowski, Tom. “The Trees Grew First: IU’s Woodland Campus.” The Ryder, April 2017, 24–25.

Ryan, John. “Letter to David F. Parkhurst,” April 30, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.

Ryan, John W. “Charge to the Class,” May 8, 1982. Indiana University commencement location, Indiana University Archives/C45/John Ryan Speeches.

Ryan, John W. “Remarks at the Sample Gates and Plaza Dedication.” Bloomington, IN, June 13, 1987. John Ryan Speeches, Indiana University Archives/C45.

Sandweiss, Eric. “Personal Communication to the Author,” June 7, 2024.

Save the Woods. “Save the IU Crescent Forest.” Real Times 6, no. 6 (February 19, 1982): 2. Originally circulated as "An Open Letter to Indiana University Alumni," February 11, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files, University Archives, Indiana University.

Schlechtweg, Harold. “Environmental Day Activities Listed.” Indiana Daily Student, April 20, 1970.

Schlechtweg, Harold. “Nelson Outlines Proposals to End National Pollution.” Indiana Daily Student, April 23, 1970.

Schuyler, David. “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Origins of Modern Campus Design.” Planning for Higher Education 25, no. 2 (1996–1997): 1–10.

Scott, Bob. “The Revolution Is Here, Escape in Dunn Meadow.” Indiana Daily Student, April 20, 1970.

S[enour], F. C. “A Novel of Indiana University.” The Vagabond 2, no. 3 (March 1925): 51–52.

Shamon, Marvin. “The Traditions of Indiana University.” Indiana University Archives/Reference file: Buildings—Bloomington Campus Well House, Rose., c1935?

Shirley, Janet Carter. The Indiana University Alumni Association: One Hundred and Fifty Years, 1854–2004. Bloomington: Indiana University Alumni Association, 2004.

Shively, George. Initiation. New York: Harcourt, Brace; Company, 1925.

Shively, George J., ed. Record of S.S.U. 585. New Haven: Brick Row Book Shop, 1920.

Slatalla, Michelle. “How the Trees Were Saved, Law Addition Flap Is Finally Over.” Indiana Daily Student, April 8, 1982. For the Opinion Board.

SmithGroupJJR. “Indiana University Bloomington Campus Master Plan,” March 2010.

Snyder, Gary.

“Coming in to the Watershed: Biological and Cultural Diversity in the California Habitat.” Chicago Review 39, no. 3/4 (1993): 75–86.

https://doi.org/10.2307/25305721.

Solberg, Winton U.

Indiana Magazine of History 67, no. 3 (1971): 268–69.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27789750.

Stahr, Elvis.

“Founders’ Day Ceremonial.” Indiana University Archives, May 3, 1967.

http://fedora.dlib.indiana.edu/fedora/get/iudl:2078062/OVERVIEW. IUA/C75.

Stoner, Richard B. “Form Letter,” April 26, 1982. David F. Parkhurst files.

Sudhalter, Richard M. Stardust Melody: The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Tandy, Jeannette Reed.

“Pro-Slavery Propaganda in American Fiction of the Fifties.” South Atlantic Quarterly 21.1, no. 1 (January 1, 1922): 41–50.

https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-21-1-41.

Tandy, Jeannette Reed.

“Pro-Slavery Propaganda in American Fiction of the Fifties.” South Atlantic Quarterly 21.2, no. 2 (April 1, 1922): 170–78.

https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-21-2-170.

“The 1915 Commencement.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 3 (1915): 278–92.

“The Centennial Commencement.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 7 (1920): 370–418.

“The Dagger: 1875–80.” Bloomington: Indiana University Archives, n.d. Reference file, Indiana University Archives.

“The Decline of Campustry.” Daily Student, November 11, 1903.

“The Guardian: Origins of the EPA.” EPA Historical Publication-1, Spring 1992.

“The New Purchase or Seven and Half Years in the Far West.” Indiana Magazine of History, n.d. unsigned review of Hall, The New Purchase (1916).

“The Old Crescent.” NRHP Inventory-Nomination Form; United States Department of the Interior: Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, 1980.

The Vision of Herman B Wells. Documentary film, 1993.

Toman, Barbara, and Christopher Cokinos. “Trustees Approve Addition Plan.” Indiana Daily Student, April 5, 1982.

Toman, Barbara, and Christopher Cokinos. “Trustees Will Re-Evaluate Plan.” Indiana Daily Student, March 8, 1982, 1, 5.

Towne, Steven E. “Indiana University During the Civil War.” 200: The Bicentennial Magazine 1, no. 2 (2018): 18–19.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

Turner, F. J. “The Significance of History.” Wisconsin Journal of Education and Midland School Journal 21, no. 10/11 (October–November 1891): 230–34, 253–56.

Ulrich, Rudolph. “Letter to Joseph Swain.” Indiana University Archives C174/B44, May 1899.

Vico, Giambattista. The New Science of Giambattista Vico: Unabridged Translation of the Third Edition (1744) with the Addition of the "Practic of the New Science". Translated by Thomas Goddard Bergin and Max Harold Fisch. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984.

Visher, Stephen S. “Water Supply Problems of Bloomington, Indiana,” Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 66 (1956): 188–91.

Weatherwax, Paul. “Familiar Trees Greet Returning Alumni.” The Review, May 1960, 12–18.

Weatherwax, Paul. The Woodland Campus of Indiana University. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1966.

Weisenburger, Francis P.

Indiana Magazine of History 74, no. 4 (1978): 367–68.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/27790338.

“Well-House Innovation.” Daily Student, October 15, 1907.

Wells, Herman B. Being Lucky: Reflections and Reminiscences. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980.

Wells, Herman B. “Letter to Burton D. Myers.” Indiana University Archives, July 18, 1941. IUA/C213/B404.

Wells, Herman B. “Letter to Roy Quinn.” Indiana University Archives, May 26, 1938. IUA/C213/B455.

Wells, Herman B. “Letter to Roy Quinn.” Indiana University Archives, May 2, 1939. IUA/C213/B455. IUA/Reference file: Foundation Day.

Wells, Herman B. “Oral History Interview by Bonnie Williams.” Wylie House Collections, March 19, 1992.

Wells, Herman B. “Letter to Dolores Lahrman.” Indiana University Archives, May 13, 1987.

Wells, Herman B. “Letter to John Ryan.” Indiana University Archives, April 7, 1987.

Wells, Herman B. “Letter to Paul Weatherwax.” Lilly institution/LMC 2283/B4/F Wells, Herman B., August 22, 1961.

Wells, Herman G. [sic]. “The Early History of Indiana University as Reflected in the Administration of Andrew Wylie, 1829–1851.” Filson Club Historical Quarterly 36 (1962): 113–27.

Williams, Bonnie. “Playing in the Stream of History: A Flexible Approach to First-Person Interpretation.” Association for Living Historical Farms and Agricultural Museums Proceedings 14 (1996): 255–61.

Williams, Bonnie, and Elaine Herold, eds. Affectionately Yours: The Andrew Wylie Family Letters, 1828 to 1859. Bloomington: Indiana University Wylie House Museum, 1995.

Woodburn, James A. “Baynard Rush Hall.” In Dictionary of American Biography, 1936.

Woodburn, James A. History of Indiana University: Volume I, 1820–1902. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1940.

Woodburn, James A. “Letter to William Lowe Bryan.” Indiana University Archives, February 28, 1935. IUA/C83/B3/F Publications, Galleys, & Transcripts.

Woodburn, James A. “Local Life and Color in the New Purchase.” Indiana Magazine of History 9, no. 4 (1913): 215–33.

Woodburn, James A. “Presentation of the History of Indiana University, Volume I at the Woodburn Testimonial Dinner.” Indiana University Archives, n.d. IUA/C83/B4/F Woodburn, James.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History I: College Men and College Life about 1850.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2 (1915): 249–69.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History II: College Men and College Life About 1850 (Continued).” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2 (1915): 409–27.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History III: Faculty and Curriculum about 1850.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 20–37.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History IV: Daniel Read, Professor of Ancient Languages, 1843–1856.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 127–48.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History V: Death of President Wylie: A Year of President Ryors and Election of Dr. Daily: Death and Services of Dr. David H. Maxwell.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 347–59.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History VI: The Vincennes Suit and the Fire.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3 (1916): 489–500.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History VII: Dark Days after the Fire: Courage in Adversity.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 4 (1917): 1–11.

Woodburn, James A. “Sketches from the University’s History VIII: The Board of Trustees Sixty Years Ago; Student Reminiscences.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 4 (1917): 117–28.

Woodburn, James Albert. “Higher Education in Indiana.” Edited by Herbert B. Adams. Bureau of Education, Circular of Information No. 1, 1891: Contributions to American Educational History. Washington: Government Publishing Office, 1891.

Woodburn, James Albert. “The New Purchase.” In Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Ohio Valley Historical Association, edited by Harlow Lindley, 6:43–54. 1. Indiana Historical Society Publications, 1916.

“Work of the Alumni Council.” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 3, no. 3 (July 1916): 397–405.

Wright, Mike. “Critics Flock to Golf Forum.” Herald-Times, December 1, 1999.

Wright, Mike. “Golf Course Alternative Offered.” Herald-Times, January 14, 2000, A1, A9.

Wright, Mike. “Golf Course Opponents Dress Like Fish, Trees.” Herald-Times, 1999-11-13.

Wright, Mike. “Group Behind New IU Golf Course Includes Alumni, Development Firm.” Herald-Times, November 30, 1999.

Wright, Mike. “Issues Raised about Golf Course’s Impact.” Herald-Times, October 13, 1999.

Wright, Mike. “IU Delays Action on a New Golf Course.” Herald-Times, December 2, 1999.

Wright, Mike. “IU Students, Staff to Have Golf Access.” Herald-Times, November 10, 1999.

Wright, Mike. “Trustees Want Public Input on Golf Course.” Herald-Times, 1999-11-24.

Wylie House Museum, Indiana University Libraries. “Wylie House Museum Handbook,” 2016–2017.

“Wylie House Music from the Parlor,” 2001. Audio recording; liner notes by Sophia Grace Travis.

Wylie, Theophilus. “Diary Entry.” Indiana University Archives, June 28, 1857.

Wylie, Theophilus. “Diary Entry.” Indiana University Archives, September 6, 1885.

Wylie, Theophilus. “Letter to Judge Andrew Wylie,” July 18, 1881. IUA/C202/B5/F Letters relating to history.

Wylie, Theophilus A. Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professor and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887. Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1890.