10 The Resurrection of Wylie House

I was always interested in anything that was a living reminder of the antiquity of the University.

—Herman B Wells, Interview

What is the most significant surviving physical artifact from the early history of Indiana University? A handful of early diplomas, handwritten letters, and published materials form a sparse but invaluable documentary record. No physical trace remains of the university’s first campus building—only an Indiana state historical marker stands on the site where IU began as the Indiana State Seminary in the 1820s. One possible candidate is the 1843 book The New Purchase; or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, which offers the first extended narrative about IU, written by its inaugural professor, Baynard Hall.

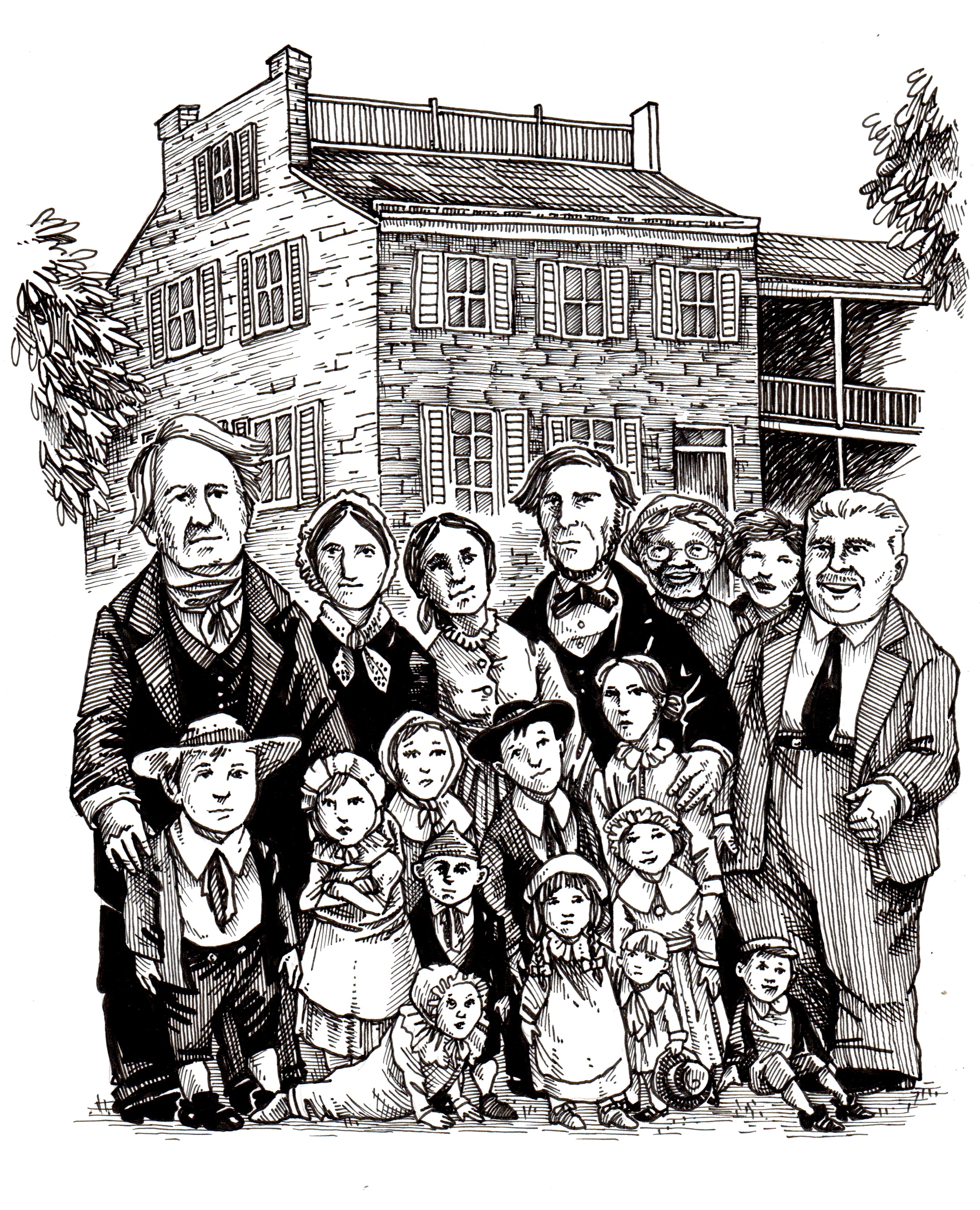

In terms of material culture as well as on programmatic grounds, a strong case can be made for the Wylie House, built in 1835 by the first IU president, Andrew Wylie, as a residence for his large family. Purchased by the university in 1947, it started functioning as a museum twenty years later but did not employ its first curator until 1983. Now, as the Wylie House Museum, it plays a central role in IU’s history and heritage activities.

When the house was built in 1835, the institution was known as Indiana College, and classes had been offered for a decade. Wylie had been in office for seven years, and student enrollment had reached forty. Located two blocks from campus, at Second and Lincoln Streets, the house was one of the finest in the area. Built of brick in the Georgian style, the house sat on a crest of land, surrounded by twenty acres, including cultivated gardens, tree plots, and outbuildings.

President Wylie guided the institution for twenty-two years until a woodchopping accident led to his death by infection in 1851. The house remained in his immediate family until 1859, when it was sold to Professor Theophilus A. Wylie, a half-cousin of Andrew Wylie, who also had a large family. That Wylie family stayed in the home for over fifty years, a period that encompassed the Civil War to the Great War. In 1915, the house was sold to IU political science professor Amos S. Hershey and his wife, Lillian S. Hershey. They owned the house for over thirty years, until it was sold to Indiana University in 1947. President Herman B Wells engineered its purchase, taking an important step in preserving the property and laying the groundwork for its eventual use as a historic house museum. Wells’s historical sensibility had been nurtured years before, starting with his involvement with another old house in Bloomington.

10.1 Living at Woodburn House

In 1932, after a couple of years as an instructor in economics at Indiana University, Herman Wells started renting rooms at the Woodburn House, 519 North College Avenue. The young teacher, thirty years old, had an interest in antique furniture and was beginning to collect English fox-hunting prints, befitting his status as a confirmed bachelor. The landlord was IU history professor emeritus James A. Woodburn, who had been living in Ann Arbor since his retirement in 1924, the same year Wells received his Bachelor of Science degree from the School of Commerce and Finance. Woodburn, who had lived in the family house since his 1856 birth, had a keen appreciation for its long history.

The house, built in 1829, was a historic structure. In 1855, his father, also an IU professor, James W. Woodburn, purchased the entire block for $1,100 and added a second story to the house in 1858. After the death of the father James in 1865, his widow took in student boarders. Their daughter, Ida Woodburn, hosted the first official meeting of the Delta chapter of the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority there in 1873. Local lore suggested that an infamous bogus

underground student newspaper, The Dagger, was started there. Later, IU faculty members, including psychologist William Bryan and political scientist Amos Hershey, resided in the house. The son James inherited the house and raised a family there.1

Wells enjoyed living in the Woodburn House and its proximity to campus. He also became acquainted with another historic house in this period—the Wylie House—which was located a half dozen blocks south of the Woodburn House. In 1915, the house had passed from the Wylie family to another IU professor, Amos Hershey, and his wife, Lillian.

Amos S. Hershey, a scion of the Pennsylvania chocolate manufacturing family, joined the Indiana faculty in 1895. A specialist in international law and diplomacy, in 1914, he was the founding chair of the Department of Political Science.2 After the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him to the US delegation to the Paris Peace Conference as a technical advisor. Lillian, a proficient singer, wed Amos in 1892. She was an active businesswoman, selling antiques and home furnishings from her residence, which she called The Old Treasure House. The Hersheys entertained often, and Wells was a frequent guest. Calling Mrs. Hershey a delightful person,

Wells recalled, Everybody knew the Hersheys. The house was most interesting, because she just lived with her antiques. She’d sell anything she had—rugs and furniture and so forth. The house was the perfect setting for that.

3 Their friendship was fueled by a shared interest in antiques and fine furnishings. Professor Hershey retired from teaching in 1932 and died the following year. Lillian Hershey continued to live in the Wylie House and operate her antiques business.

In 1933, Wells took a leave of absence to serve the state of Indiana as it reorganized its financial institutions during the Depression. A banking wunderkind, he analyzed the banking system in Indiana and supervised a team that rewrote the state’s banking laws in early 1933. The reform legislation passed under the governorship of Paul McNutt, former dean of the IU School of Law, creating a new Indiana Department of Financial Institutions. Wells served in three capacities: as secretary to the Commission on Financial Institutions, bank supervisor, and supervisor of the Division of Research and Statistics for the department. This triple role gave him great authority in regulating the state’s banking system—and a comfortable salary to indulge his taste for antiques and fine furnishings.4

In 1935, Wells moved from teaching to administration when he was appointed dean of the IU School of Business Administration by President William Bryan. He continued his meteoric administrative rise two years later, when the board of trustees selected him as acting president after Bryan retired after thirty-five years. Wells was in office for only a few weeks when he noticed that Lillian Hershey had put the Wylie House on the real estate market, and he began a warm correspondence with her.5 At the August 1937 meeting of the trustee board, acting president Wells reported to the trustees that the Wylie House was for sale, listed at $30,000. Further discussion by the board was planned but apparently not memorialized.6 Wells continued to serve as acting president for nine months, fulfilling day-to-day responsibilities as well as launching an ambitious university self-study, before being named the eleventh IU president in March 1938.7

10.2 Paying Tribute to Andrew Wylie

Two months later, in May 1938, the new president received a letter from Roy Quinn, an Indianapolis resident, lamenting the neglect of the first president, Andrew Wylie, on the recent Foundation Day, a celebration of the university’s heritage. Ruing that he was not a University man

despite his rearing in Bloomington, Quinn admitted, I learned to love old I.U. and revel in its glorious past and pull for its promising future.

He observed that, over the half century he had been visiting Bloomington’s Rose Hill Cemetery, he had never seen a flower on Wylie’s grave. He suggested, With a band and military units and everything else needed to make such a thing a success why not lay a wreath upon the grave of the original

8forgotten man

?

In his reply, Wells agreed that the university should pay tribute to Wylie and suggested that a committee of the senior class place a wreath on his grave each Foundation Day. This would cause students to remember Dr. Wylie,

he thought, more than any other action I can think of.

9 The next year, Wells oversaw an expansion of the 1939 Foundation Day commemoration, with activities not just in Bloomington but also around Indiana (Kokomo, Marion, Anderson, Terre Haute, Fort Wayne, North Vernon, Michigan City, Rushville, Muncie, Washington, Decatur, Peru, Spencer, South Bend, Evansville, and Salem) and in other states (St. Louis, St. Petersburg, Boston, Champaign, Iowa City, Denver, Grand Rapids, Louisville, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, New Haven, and Detroit).10

Wells wrote to Quinn again, telling him that a pilgrimage to the gravesite of Andrew Wylie was planned as part of the Foundation Day activities and inviting him to come. These services mark the fulfillment of an idea you had a year ago this month,

Wells wrote, and I hope they may become a part of Indiana University’s tradition for all the years to come.

11 Demonstrating Wells’s ability to harness an unexpected suggestion into a university priority, the Wylie pilgrimage was the first stirring of a new tradition.12

The tradition became an annual event, continuing throughout the war years (with one exception in 1944). President emeritus Bryan was a frequent participant along with President Wells and student leaders. In 1945, the 125th anniversary of the university was celebrated at graduation ceremonies, and the commencement speaker, Ralph Cooper Hutchison, president of Washington and Jefferson College, attended the pilgrimage and laid the wreath on Wylie’s grave. (Wylie had been president of both colleges sequentially before coming to IU, and in 1816, he unsuccessfully attempted to merge them.)13 For the decade after the war, the pilgrimage remained a part of the celebration of the university’s founding, known as Founders Day after 1951.14

10.3 The Purchase of Wylie House

During the war, the director of the university library, Robert Miller, put together an ad hoc archives committee to preserve and care for documentation of the university’s past.15 The president’s suite in Bryan Hall, constructed in 1936, was built with a five-floor archival unit attached, called the President’s File Room. It contained a vast collection of documents generated during the thirty-five-year administration of former president Bryan as well as copies of past official catalogs, bulletins, and printed announcements and programs. Wells, aware of the need for good recordkeeping, acceded to the plan to rename the space the University Archives and put librarian Mary Craig in charge. His secretaries kept his presidential files in good order. A sign was posted in the room:

NOTICE!

No person shall take any paper of any sort from this room without giving a receipt therefor to the file clerk, who is made directly responsible to the Trustees of the University. This order applies to all persons, including the undersigned.

HERMAN B WELLS

The notice humorously underscored Wells’s egalitarian convictions.

After the Second World War ended in 1945, Wells kept his eye on the Wylie House and continued his correspondence with Lillian Hershey, sharing their interest in antiques and decorative objects. The president was still living in the Woodburn House and found it was well suited for entertaining and other official functions. (James Woodburn had given the house to IU in 1941, two years before his death.)16

Wells used the opportunity of a postwar visit by Governor Ralph Gates in 1947 to put into motion an ingenious plan. On a tour around campus and the city, Wells and Gates drove by the Wylie House. The governor was suitably impressed and urged Wells to put the funds to acquire the property on the university’s 1947 budget request.17 The purchase went through, and Wylie House became an institutional property after 112 years of service as a family home. The terms included a provision for Mrs. Hershey to live in the house four years without paying rent or taxes. When she moved to Florida in 1951, the university took possession.18

University archivist Craig, who had received a Master of Library Science degree from Columbia University, turned out to be less interested in the written record than in the material culture of the past, and she soon added to her responsibilities the role of unofficial but acknowledged caretaker of the Wylie House. Both Wells and Craig were aficionados of antique furniture and historic houses, and the prospect of furnishing the Wylie House in period pieces was enticing to each. In their quest for antiques, Wells and Craig used campus storage spaces, including the attic of Wylie House, to hold accumulating treasures of furniture and other furnishings.

In October 1951, two grandchildren of Theophilus Wylie joined the trustee board for lunch: sister and brother, Mrs. Morton Bradley (née Marie Boisen), from Boston, and Mr. Anton Boisen, from Chicago. They provided valuable background information about the house and some of its former occupants. Also, family letters, receipts, and other documents were conveyed to the University Archives. Soon after, the trustees discussed four options for the Wylie House:

- Establish the house as a museum, to depict in detail how a scholar of the 1830’s lived, worked, and entertained. Much of the original furniture is available, and we know exactly where it was placed.

- Restore the house as it was, or in the style of the period, with some additional comforts, and use as a guest house. It would be incorporated into either the Halls of Residence or the Union system. Such usage is common in other universities.

- Restore the house structurally and use it for headquarters for some group such as the Alumni Association.

- Restore the house structurally and use it as one of the home management houses.19

Although the board favored the guest house option, action was deferred. In 1953, with university office space at a premium, Wylie House was pressed into service as the temporary headquarters of IU Press, launched in 1950.20 The university press office stayed in the building until 1959. Craig corresponded with another grandson, T. A. Wylie, at the end of 1954 and early 1955, sending him a Wylie family tree and exchanging other information.

10.4 Remembering Andrew Wylie

Although Wells was familiar with the first president’s house and had engineered its purchase for the university, Andrew Wylie the man and his influence on IU were a mystery. In the spring of 1960, after announcing his impending retirement two years hence, Wells renewed his attention to the house associated with the original campus at Second Street and College Avenue. In support of the idea that the house should be restored to its original appearance, he further publicized the legacy of Andrew Wylie.

In November 1960, Wells gave a speech at Louisville’s Filson Club, a venerable history society dedicated to Kentucky and the Ohio River valley. The speech was published in the club’s history quarterly under the title The Early History of Indiana University as Reflected in the Administration of Andrew Wylie, 1829–1851,

under Wells’s byline. He claimed that Wylie, almost forgotten outside of IU circles, was a notably important figure in the early development of western state universities.

The more he knew about Wylie, the more determined he became to bring Wylie’s legacy to light.

With the aid of IU archivists and historians, Wells pieced together his narrative account from the few surviving sources, including contemporary reminiscences from peers and students, to portray Wylie’s personality and career as an educator. He summed up his contributions under four categories: establishing the curriculum, promoting good student-faculty relations, serving as chief spokesman for higher education, and mounting successful defenses of the university against outside forces.21 Wells concluded with a salute to his predecessor:

If the Indiana University of today is an institution of immeasurable value and service to the state and nation, and I firmly believe that it is, we must revere the memory of the first president who offered the intellectual and moral leadership so vital and necessary to the University in its infant days. He gave stability in a period characterized by instability. A university is a durable institution, built on the accumulated wisdom of the past. How fortunate that our past included Andrew Wylie!22

By the time Wells’s article appeared in print in 1962, the Wylie House restoration was underway.23

Andrew Wylie’s legacy was emerging as a touchstone for the university’s past, and his home was a material embodiment of that legacy. It was a visible sign of the university’s rich cultural heritage, and its curation and interpretation would provide varied ways to connect to IU’s history.

10.5 Wylie House Restoration

The Edward D. James architectural firm was selected to perform the long-delayed renovation of the Wylie residence and produced a condition report for the university in late 1960. The project was termed a restoration,

which meant renovating the structure to resemble its original finished appearance in 1835.

Architect Edward James had experience in historic preservation and, in 1957, was appointed American Institute of Architects (AIA) preservation officer for the state of Indiana, where he coordinated the Historic American Building Survey Inventory. His younger associate, H. Roll McLaughlin, was assigned as project architect for the Wylie House restoration. In 1960, McLaughlin was appointed AIA assistant preservation officer, working under James. Later that year, McLaughlin was elected first vice president of the new Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana (now Indiana Landmarks), a nonprofit organization formed by civic and business leaders interested in the preservation of architectural heritage.24 Drafting plans for the Wylie House restoration, McLaughlin embarked on an important early project at the outset of his long career.25

McLaughlin relied on his architectural training and understanding of the principles of historic preservation to guide the project. In the fall of 1960, McLaughlin spent ten weeks in Europe studying preservation techniques and stopped by Washington, Pennsylvania, where Andrew Wylie lived prior to coming to Bloomington.26 (Nationwide design standards were not instituted until 1966, when the National Historic Preservation Act was passed.) Motivated by a sense of original intent, he focused narrowly on the architectural creation of the house in 1835 rather than considering the entire eighty-year span during which two related, yet separate Wylie families were in residence. The goal was to restore the house to the year it was built.

The IU trustee board approved an agreement with the Edward D. James firm in January 1961, with a preliminary cost budget of $250,000, with a justification: Because of the nature of the work, which precludes definite advance plans and specifications, this will be done on a time-card basis cost of work done.

27 In June 1961, President Wells appointed a Committee on the Restoration of Wylie House, chaired by Joseph Franklin, longtime IU treasurer, and including archivist Mary Craig, physical plant director H. H. Brooks, librarian Cecil Byrd, landscape architect Frits Loonsten, and architect Edward James.28

The actual renovation work was done by IU physical plant employees, around fifteen in all, supervised by John Dixon, a master carpenter. The initial phase, lasting about a year, stabilized the foundation, rebuilt the west wall, repointed all exterior walls, rebuilt fireplace hearths, removed the roof, and removed plaster from interior walls. For the next three years, a variety of finish work occurred. A new roof, with poplar shake shingles split by physical plant employee Wally Sullivan, was installed, and copper guttering was added. Interior walls were re-lathed and replastered. In the kitchen, the floor joists were replaced and the floorboards too, with old-growth poplar flooring. The back porch, including its foundation, was removed. Wood trim was stripped and repainted, exterior doors and some windowsills were replaced, new limestone steps were installed at entrances, and most windows were reglazed with antique glass. The attic was reconstructed, with new walls, doors, stairs to the roof, and a roof access hatch with copper hinges. The main staircase was carefully disassembled, stripped of paint, reassembled, and repainted.29

As the restoration project continued, in 1962, the university got a new president, Elvis J. Stahr, and Herman Wells moved into the role of university chancellor, a new senior administrative post. The traditional pilgrimage to Wylie’s grave in Rose Hill Cemetery on Founders Day went on, now led by President Stahr and joined regularly by Wells.

10.6 Wylie House Museum

Indiana University issued a press release announcing the opening of the museum to the public in October 1965. It fell to the university archivist, Mary Craig, to keep the place running. With no additional staff and little interpretation, by default the museum focused on the building itself in its renovated state. After the initial flurry of publicity, the museum was open by appointment. Craig continued to acquire period furnishings, and those that were not put on display immediately were consigned to storage at the university. There was little attempt to curate the history of the house as successive families lived there. There was, however, a trove of documents slowly gathering in the archives, through occasional gifts and the rediscovery of materials already in the archives that had been poorly cataloged previously.

Preceding the 1967 pilgrimage to Wylie’s gravesite, President Stahr led a special Founders Day ceremony to commemorate the centennial of the admission of women to IU. A total of six women received honorary degrees. Then Stahr invited the audience to join him and Wells for

a pilgrimage to the grave and then to the house of Andrew Wylie, first president of Indiana University. Wylie House was purchased for the University at the express request of Governor Ralph Gates, who instructed that it be restored to its original form. The necessity of collecting funds for the renovation and the time required to do the actual work postponed the opening until two years ago. Since then, increasing numbers of students, parents, school children, and others have toured this home of so much historical significance to Indiana University and to the State. I should add, Wylie House gives some continuing reality to our annual Founders’ Day reminder that ours is a pioneer university.

Charter bus transportation was available from the Indiana Memorial Union.30

During the 1970 IU sesquicentennial year, records indicate that an application for nomination of the Wylie House to the National Register of Historic Places was begun by IU staff but not completed.31 In 1972, Chancellor Wells bought a neighboring house as a real estate investment to protect Wylie House and help buffer possible future development.32 In 1976, the United States bicentennial brought renewed attention to local landmarks, including several historic structures in Bloomington connected to the university. A flurry of successful listings on the National Register of Historic Places was completed, including the Monroe County Courthouse (1976) and the Carnegie Library (1978).33 Three properties with strong links to IU were listed: the Wylie House (1977), Seminary Square Park (1977), and the Old Crescent (1980).34 Coincidentally, Mary Craig retired in 1977, but she remained active. In 1978, the home next door was purchased by the university, dubbed the Wylie House Annex, and provided office space and additional storage.35

In the third volume of Thomas Clark’s massive sesquicentennial history of IU, he mentioned the Wylie House in passing, calling it an institutional shrine

to the university’s past and a memorial of

36 The vision that animated the restoration of the house’s architectural glory in the 1960s had dissipated in the 1970s, and Wylie House remained an architectural relic, impassively witnessing the passing years.Andrew the First.

10.7 Curatorial Beginnings

The annual pilgrimage to Andrew Wylie’s gravesite and to the Wylie House had continued, with President John Ryan leading the party in 1983. The home, Ryan noted, was a mansion almost beyond comprehension

in its day.37 That year, Bonnie Williams was hired as the first curator of Wylie House. With determination and energy, Williams launched into making the house more than an architectural relic.

Williams, who was the only staff member at the Wylie House, did have a small group of volunteers who helped with research and visitor relations and interpretation. For the first few years, the house had limited public hours, and, in her words, interpretation was confined to standard third-person tours describing the collection and giving some historical background about the Wylie family and early Indiana University.

38

In 1991, one volunteer, who had worked previously as a first-person interpreter at another historic site, was eager to try first-person techniques at the Wylie House. Williams was skeptical about whether there was enough research into the Wylie family and their daily life to support the creation of a living-history character, as well as how to deal with certain anachronistic features of the house, such as electrical outlets and a security system.

After more reading and discussion, however, Williams was willing to try it. Using a my time / your time

approach, Williams was inspired to create a first-person ghost interpretation.

The idea was that the character worked in the context of a recreated past but could call on a knowledge of past and future events as needed to help explain the story to visitors.

39 Williams, dressed in the style of the 1840s, greeted fourth graders who were on a field trip to the historic house:

Good morning and welcome to all of you! Mrs. Williams, who looks after Wylie House, told me she was expecting a group of young visitors this morning. She thought you might enjoy it if I showed you the house and told you a little about what it was like when I was a girl here. I said I’d be most pleased to do so. I enjoy talking about old times. Of course, 150 years is a long time to remember back! But I will say, my memory has always been sharp. My name is Elizabeth Wylie. You may call me Miss Wylie. Andrew Wylie was my Papy, and this is the home I grew up in many, many years ago. Oh, my dears, what memories.… Let’s go into the parlor where we can sit and visit for a spell.40

Williams explained the rationale behind the approach: Instead of transporting visitors back in time and pretending it is the 1840s, I bring someone from the 1840s into the present—a

41ghost,

so to speak.

By playing a ghost, the interpreter had access to knowledge about the past as well as the present, providing flexibility in answering questions about the house or its furnishings. Even obvious anachronisms, such as the motion detectors for the security system, could be explained. The ghost of Miss Wylie answered when a schoolchild pointed out the small plastic box with a blinking red light in the corner of a room:

You know, I studied on that for the longest time. It certainly wasn’t here when I was a girl. Finally I asked Mrs. Williams and she told me it was a burglar alarm! I told her that when I was a girl, our

burglar alarmwas our dog! Well, in those days there was always someone in the house, and nowadays that’s not so, and we don’t have a dog here anymore to protect the house. So I suppose it is a good idea to have one of these new burglar alarms, just to be on the safe side.42

Williams admitted that the ghost approach necessitated a lot of background research to be able to respond to visitors’ observations and to answer questions, but in the end, we talk about what we do know.

43 At the end of the group tour, Williams came out of character: As you know, I am not really a ghost. I am an historian. It’s my job to learn about the past and to share what I’ve learned with you. And I have found that sometimes the best way to do that is to pretend, like we did today. I enjoyed sharing and learning with you! Do you like studying history this way? Maybe someday some of you will become historians, and you may even do work like this!

44 Both children and adults responded well to this conclusion, which gave the tour a sense of closure and provided the opportunity to ask questions about the museum.

Williams used and refined her ghost interpretation at the Wylie House for nearly a decade for visitor tours. She also practiced a form of historical reenactment, where a small group would get into character as various members of the Wylie family and read their nineteenth-century letters to each other.

In the 1990s, some house features needed additional remediation. In 1994, the trustee board officially renamed the facility the Wylie House Museum, to better reflect its function.45 In 1995, a wheelchair ramp was installed, which required excavation on the north side. Some artifacts were found, mostly bits of broken china, and cleaned and cataloged. Another conservation assessment survey was completed in 1995.

In 1995, volunteer researcher Elaine Herold, aided by curator Williams, published a compilation of 163 letters exchanged by the members of the Andrew Wylie family. The project was made possible by an Indiana Heritage Research Grant from the Indiana Historical Society and the Indiana Humanities Council. Under the title Affectionately Yours: The Andrew Wylie Family Letters, 1828 to 1859, the book gives glimpses of the mid-nineteenth-century Hoosier life of the first family of IU.46 The letters reveal information about travel, weather, and academic life, as well as family drama and emotion about courtship and marriage, sickness and death. By showing the rich texture of day-to-day living, the collection of letters humanizes the Wylie family as they faced the perennial challenges of life.

An eighteenth-century fortepiano surfaced in IU storage in 1997, having lain there for decades. Curator Williams and the Wylie House Museum volunteers were excited, thinking that it might be the one that Andrew Wylie brought to Bloomington in 1829. Despite extensive research, the fortepiano’s provenance was murky. It likely belonged to the Wylies but could not be proven conclusively. In any event, plans were made to restore the instrument, built in 1795 by the Broadwood Company in England. Local harpsichord craftsman Theodore Robertson rebuilt the instrument. Based on a bibliography of the Wylies’ own sheet music, musicians searched the Lilly Library for appropriate period music that represents what the Wylie family would likely have experienced.

In 2001, an audio recording, Wylie House Music from the Parlor, was produced, played on the Broadwood fortepiano and featuring two pianists and two vocalists.47

With funds provided by state and federal grants, Williams started preparing a bibliography of Andrew Wylie with the aid of stalwart volunteers. Published in November 2000, Andrew Wylie: A Bibliography was edited by Diane Chaudemanche and Elaine Herold. It contained an annotated list of seventy-three primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, plus a short list of artifacts associated with Wylie, including the house.48

10.8 Jo Burgess and the Education Center

Jo Burgess, former head of Preservation Services at IU Libraries, became the director of the Wylie House Museum at the beginning of the 2000–01 academic year.49 She had a knack for physical artifacts and an aesthetic that was historically informed. In her first year, a consultant produced a thorough analysis of the house’s history and current state of preservation.50 The Wylie House Historic Structure Report made sober reading, with several serious threats to the house’s historical fabric identified. Next door, the Wylie House Annex had had substantial structural issues ever since it was acquired that made it nearly impossible to control environmental conditions.

In her first years, Burgess had the white walls decorated with historically appropriate colors, embellished by artful stencil work. She compiled an index to the family letters contained in Affectionately Yours and published a second edition in 2002. After that, an unexpected trove of more letters was acquired by the Wylie House Museum, consisting of several hundred from the Theophilus Wylie family and another one hundred letters from the Andrew Wylie family. Several letters found their way into the third edition of the book, published in 2011.51

Burgess made concerted efforts to expand educational programming. In summer 2005, she hired a full-time curator of education—Bridget Edwards—who had a doctorate in anthropology.52

Aided by the dean of university libraries Suzanne Thorin, Edwards got on the radar of the university administration in 2006, when the trustees heard a brief presentation by Vice President Clapacs on the idea of adding an education center to the museum facilities.53 In 2008, the education center project was approved, and in 2009, contracts were let to design and build the education center.54 In May 2010, the trustees approved the naming of the new facility after a descendant of Theophilus Wylie, the Morton C. Bradley Jr. Education Center.55 Personnel changes ensued, starting with the departure of education curator Edwards in 2011, followed by the retirement of director Burgess in 2012.56

10.9 The Recent Past

When Burgess retired in 2012, librarian Carey Beam became the next museum director, carrying on the tradition of engagement with both the Bloomington community and the larger communities related to nineteenth-century American history and culture. In the Wylie House Museum Handbook of 2016–17, a guide for staff and volunteers, the basic mission of interpreting the early history of IU and Bloomington remained the same but was elaborated in the following way:

The mission of the Wylie House Museum is to preserve, collect, and study the house, its artifacts, documents, and landscape, and through them to interpret with the public the early history and culture of Indiana University and the town of Bloomington. We seek to engage the visitor in an experience of history which is stimulating, thoughtful, and enjoyable; which is factually accurate and respectful of the period and people we interpret; and which excites an interest in and appreciation of domestic history, the heritage of Indiana University and Bloomington, and the visitor’s own personal history.57

The mission statement also emphasized the ongoing historical research program involving the museum’s buildings, collections, landscape, and archives, noting that all of it is part of the university’s teaching and research mission.

10.10 Connecting to the Past

At the gala sesquicentennial dinner in 1970, University Chancellor Wells paid tribute to his presidential predecessors. He talked about the rich store of anecdotes and recollections about the early life of the university

possessed by President Bryan, who had lived in Bloomington for ninety-five years and had been associated with the university during his entire adult life. Bryan knew friends of the first president, Andrew Wylie. And the first president, so it was alleged, had met George Washington when he was a boy. Wells continued the story, smiling, It was my later good fortune to share with Dr. Bryan remembrances of things past. They became so much a part of me that I find myself occasionally reminiscing about George Washington.

The audience roared with laughter.58

Wells was using humor to convey a serious point about the human need for connection to the past. Appreciating those who came before, whether in our families, communities, or institutions, is a vital part of our common heritage. In his ninetieth year, Wells reflected on this during an interview with Bonnie Williams, the first curator of the Wylie House, saying, I was always interested in anything that was a living reminder of the antiquity of the University.

59 He became acquainted with the Wylie House in the early 1930s. When he became president later in the decade, he set his sights on acquiring the house for the university, which took him ten years. It was another decade and a half before the house received an architectural restoration. During the sesquicentennial era, as historian Clark noted, it was an institutional shrine.

Exquisitely restored to its architectural glory, it was a relic admired from afar, but with tenuous connections to the ongoing life of the university. In the 1980s, interpretative programs and cultural research on the home and its inhabitants reengaged the Wylie House with its local context. Renewed financial and programmatic investments by the university after 2000 had ensured the welfare of the Wylie House Museum during IU’s bicentennial era. Throughout his long life, Herman Wells played a catalytic role in the resurrection of Wylie House, the most significant artifact relating to the early history of Indiana University.

“The Dagger: 1875–80” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives, n.d.). Reference file, Indiana University Archives;

Delta: The Early Years

;Woodburn House

↩︎Oliver P. Field, Political Science at Indiana University, 1829–1951 (Bloomington: Bureau of Government Research, Department of Government, Indiana University, 1952).↩︎

Herman B Wells, “Oral History Interview by Bonnie Williams” (Wylie House Collections, March 19, 1992).↩︎

See Herman B Wells, Being Lucky: Reflections and Reminiscences (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), Chapter 4; and James H. Capshew, Herman B Wells: The Promise of the American University (Bloomington; Indianapolis: Indiana University Press; Indiana Historical Society Press, 2012), Chapter 3.↩︎

“Hershey, Mrs. Amos Shartle” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives, n.d.). IUA/C213/B268/F.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 August 1937” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, August 9, 1937), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1937-08-09.↩︎

Roy Quinn, “Letter to Herman Wells” (Indiana University Archives, May 16, 1938). IUA/C213/B455.↩︎

Herman B Wells, “Letter to Roy Quinn” (Indiana University Archives, May 26, 1938). IUA/C213/B455.↩︎

“I.U. Founding to Be Observed by Alumni Throughout the World,” Indianapolis News, May 2, 1939, 13.↩︎

Herman B Wells, “Letter to Roy Quinn” (Indiana University Archives, May 2, 1939). IUA/C213/B455. IUA/Reference file: Foundation Day.↩︎

“Inaugurating What Is Expected to Be an Annual Custom,” Indianapolis Star, May 5, 1939, 17. Photo caption. Pictured: Albert Higdon, president of the senior class; Herman Wells; Mrs. Harry A. Axtell, granddaughter of President Wylie; Miss Madeline, great-granddaughter of President Wylie; William Bryan.↩︎

Before he assumed the IU presidency, Andrew Wylie was president of both Jefferson College and Washington College, located a dozen miles apart. He attempted unsuccessfully to merge them in 1816; they were united in 1865.↩︎

Pilgrimage records are spotty; no documents have surfaced for 1946 and 1948.↩︎

(Bloomington: Indiana University Archives, n.d.). IUA/C213/B30/F.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 10 October 1941–11 October 1941” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, October 10, 1941), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1941-10-10.↩︎

Thomas D. Clark, Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume III: Years of Fulfillment, 4 vols. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977), p. 150, 180–181. See also Wells, “Oral History Interview by Bonnie Williams”.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 12 June 1947–14 June 1947” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 12–14, 1947), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1947-06-13; Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 30 June 1947” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 30, 1947), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1947-06-30; Capshew, Herman B Wells, 184–85.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 16 November 1951” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, November 16, 1951), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1951-11-16.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 01 December 1952” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 1, 1952), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1952-12-01; Capshew, Herman B Wells, 185, 203–4.↩︎

Herman G. [sic] Wells, “The Early History of Indiana University as Reflected in the Administration of Andrew Wylie, 1829–1851,” Filson Club Historical Quarterly 36 (1962): 113–27.↩︎

Among the leaders of Historic Landmarks Foundation of Indiana were Eli Lilly and Herman Krannert. H. Roll McLaughlin, “HABS in Indiana, 1955–1982: Recollections,” in Historic American Buildings Survey in Indiana, ed. T. M. Slade (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983), 13–20, pp. 16–17.↩︎

Preservation Development Inc., “Wylie House Historic Structure Report” (Bloomington, 2001).↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 20 January 1961–21 January 1961” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, January 20–21, 1961), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1961-01-20.↩︎

Preservation Development Inc., “Wylie House Historic Structure Report,” 13–14.↩︎

Elvis Stahr, “Founders’ Day Ceremonial” (Indiana University Archives, May 3, 1967), http://fedora.dlib.indiana.edu/fedora/get/iudl:2078062/OVERVIEW. IUA/C75.↩︎

Preservation Development Inc., “Wylie House Historic Structure Report,” 16.↩︎

The address was 215 E. Second Street. Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 22 September 1972” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 22, 1972), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1972-09-22.↩︎

Dana D’Esopo, co-chair of the Historic Preservation Subcommittee filled out the courthouse form; Bruce Tone and Dana D’Esopo, Save the Library Committee, filled out the library form.↩︎

Donald Carmony, IU professor of history and editor of the Indiana Magazine of History, and H. Roll McLaughlin, restoration architect, filled out the form for the Wylie House; Mary Alice Gray of the Bloomington/Monroe County Bicentennial Commission for Seminary Square; and Daniel F. Harrington of the IU Heritage Committee for the Old Crescent.↩︎

Preservation Development Inc., “Wylie House Historic Structure Report,” 21.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 April 1983” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, April 9, 1983), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1983-04-09.↩︎

Bonnie Williams, “Playing in the Stream of History: A Flexible Approach to First-Person Interpretation,” Association for Living Historical Farms and Agricultural Museums Proceedings 14 (1996): 255–61.↩︎

“Playing in the Stream of History”., p. 255. See also Stacy Flora Roth, Past into Present: Effective Techniques for First-Person Historical Interpretation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), where Williams’s technique is discussed on page 17.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 24 September 1994” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 24, 1994), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1994-09-24.↩︎

Bonnie Williams and Elaine Herold, eds., Affectionately Yours: The Andrew Wylie Family Letters, 1828 to 1859 (Bloomington: Indiana University Wylie House Museum, 1995).↩︎

“Wylie House Music from the Parlor,” 2001. Audio recording; liner notes by Sophia Grace Travis.↩︎

Diane Chaudemanche and Elaine Herold, eds., Andrew Wylie: A Bibliography, 2000, http://hdl.handle.net/2022/20329.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 15 September 2000” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, September 15, 2000), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2000-09-15.↩︎

Preservation Development Inc., “Wylie House Historic Structure Report”.↩︎

Jo Burgess, ed., Affectionately Yours: The Andrew Wylie Family Letters, I: 1828–1859, II: 1860–1918 vols. (Bloomington: Wylie House Museum, 2011). Volume I: https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/items/4323e65e-8053-4624-a19c-cec3c14205f0; Volume II: https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/items/4c56273e-06d6-427e-a533-769e9cf5504e.↩︎

Edwards served from July 2005 to September 2011.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 09 June 2006” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, June 9, 2006), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2006-06-09.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 15 August 2008” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, August 15, 2008), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2008-08-15; Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 14 August 2009” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, August 14, 2009), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2009-08-14.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 07 May 2010” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, May 7, 2010), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2010-05-07.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 07 December 2012” (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Archives; Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, December 7, 2012), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/2012-12-07.↩︎

Wylie House Museum, Indiana University Libraries, “Wylie House Museum Handbook” (2016–2017), 3.↩︎

The Vision of Herman B Wells, Documentary film, 1993, 47:15–20.↩︎