2 The First Historian

Human beings participate in history both as actors and as narrators. The inherent ambivalence of the word history

in many modern languages, including English, suggests this dual participation. In vernacular use, history means both the facts of the matter and a narrative of those facts, both what happened

and that which is said to have happened.

The first meaning places the emphasis on the sociohistorical process, the second on our knowledge of that process or on a story about that process…. The inability to step out of history in order to write or rewrite it applies to all actors and narrators.

—Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History

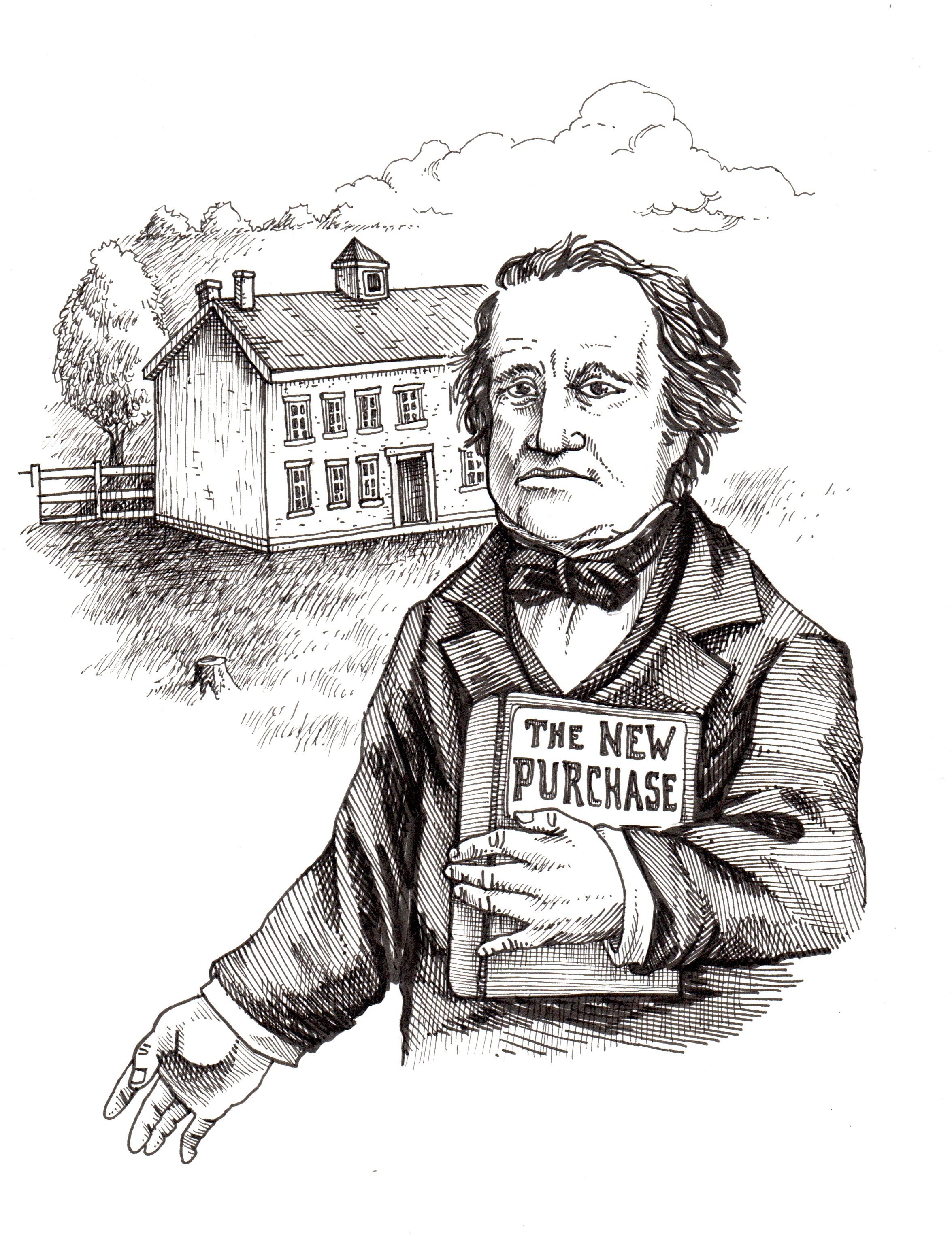

Few people today are familiar with the Reverend Doctor Baynard Rush Hall (1798–1863), the inaugural instructor at the progenitor of Indiana University—the Indiana State Seminary of learning. The school was chartered by the state legislature in 1820, and Hall served as principal from its opening in 1825. When the tiny institution was elevated to Indiana College in 1828, it acquired its first president, Andrew Wylie, who also served as an instructor. In 1832, Hall left the institution following an administrative struggle with President Wylie. The thwarting of his ambitions motivated Hall to write a lightly fictionalized account of his Bloomington career, The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, published in 1843 in two volumes.1

In addition to its endurance as a vivid description of pioneer life in southern Indiana, the book serves as a uniquely valuable source on the early history of Indiana University. IU’s historiography has been shaped by Hall leaving and Wylie staying for the rest of his career. Thus, the first written accounts of institutional history describe the faculty war

ending with the termination of Hall. Ever since, the historical role of Hall has been impoverished, relegated to the margins of IU’s institutional saga.

Hall thus was not only the first instructor, teaching Greek and Latin in the classical curriculum, but also the first historian of the institution. To be sure, he narrated history in a partisan manner, outlining what he saw as Wylie’s mistaken approach, but the factual details about college life have been generally accepted. Indeed, early IU historians wove Hall’s recollections, sometimes without attribution, into their narratives. As living memory faded over time, Hall’s book became an increasingly important historical source. Because his activity as a historical narrator has been neglected, a closer examination of his foundational role in the university’s historiography might yield deeper understanding.

2.1 From the Metropolis to the Frontier

A Philadelphia native, Baynard Hall received his bachelor’s degree from Union College in Schenectady, New York, in 1820. He then attended Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey, obtaining a certificate in 1823, and received a license to preach from the Presbyterian ministry. Hall and Mary Ann Young were married in 1820, in Danville, Kentucky. Their two young children died in 1824. Propelled by a mixture of frontier fascination and personal tragedy, Baynard Hall and his wife left Philadelphia in April 1824, bound for Owen County, Indiana, where other members of the Young family had settled. Baynard was twenty-six, and Mary Ann was twenty-eight. Completing their journey by stagecoach in May, they arrived in Owen County, near the northern limit of white settlement in the new state.2

Meanwhile, the Indiana State Seminary of learning was being organized by a board of trustees. Endowed with a federal land grant, the trustees located the school in Bloomington, a new settlement established in 1818. The campus was carved out of the forest a few blocks south of the Monroe County courthouse. A two-story brick Seminary Building went up, as well as a professor’s house, as ten acres of land were cleared for the school.

In November 1824, Hall was hired by the trustees as the sole instructor a few months before the seminary opened. Newspaper advertisements described the young instructor: Mr. Hall is a gentleman, whose classical attainments are perhaps not inferior to any in the western country; and whose acquaintance with the most approved methods of instruction in some of the best universities in the U. States, and whose morals, manners, and address render him every way qualified to give dignity and character to the institution.

3

The description of the campus was similarly embellished: [The buildings] are erected on an elevated situation, affording a handsome view of Bloomington the county seat…and also a commanding prospect of the adjacent country which is altogether pleasant and well calculated for rural retreats; and as it regards the healthiness of its situation, we hazard nothing in the assertion, that it cannot be excelled by any in the western country.

4

The Indiana State Seminary of learning opened for classes in April 1825, with Hall welcoming around ten young men. Hall continued to serve as an instructor for the infant institution until 1832. In those seven years, student enrollment increased from ten to forty. The faculty was expanded to two in 1827, with the addition of John Harney to teach mathematics, and to three in 1829, with the hiring of Andrew Wylie to serve as president of the institution, now known as Indiana College, as well as to teach mental and moral philosophy, political economy, and literature.

Hall left the college under a cloud in 1832, as did Harney, because of personal differences with President Wylie. Harboring bitter disappointment, Hall and his wife traveled back east. Never returning to the scene of his professional origination, the classical scholar spent the rest of his life teaching and preaching at a series of schools and churches in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York.5

Hall became a published author in 1836 with a Latin grammar textbook, which was reviewed harshly.6 In 1843, Hall published his second book, detailing his time in Indiana. The New Purchase chronicled how pioneer Hoosiers cultivated life on the frontier, including colorful descriptions of daily activities of subsistence, transport, social mores, and religious observance.7 The book’s title was the common name of the middle third of Indiana, after resident Indian tribes ceded their land to the United States in the Treaty of St. Mary’s. The book has defied easy literary categorization: written as a nonfiction composition, it was presented as a quasi-fictive work.8 It contains aspects of autobiography, memoir, and travelogue, leavened with personal diatribes directed against Wylie.

To tell his side of the story, Hall adopted an unusual approach. The cutting satire that bordered on defamation in his statements pertaining to Wylie motivated Hall to invent names for characters and places in The New Purchase. Since he was both the narrator and the chief protagonist, he devised twin alter egos, identifying pseudonyms for the author, Robert Carlton, Esq., and for the professor, Reverend Charles Clarence. Carlton was also given the role of trustee (which Hall was not).

The preface is a dialogue between Carlton and Clarence about history, fiction, and truth. Regarding the contents of the book, Carlton estimates that the Truth is eight parts out of ten, the Fiction only two:—that the Fiction is mainly in the colouring and shading and perspective…in the aggregation and concentration of events, acts, actors…that the Chronology of the whole and the parts is in need of some rectification.

9

In discussion about its title, Carlton suggests to Clarence, Whereabouts? or Seven and a Half Years in a New Purchase of the Far West; being a Poetic Dream at Sun Rise, with a Prosaic Reflection as Sun Set—a Novel-History, and a Historic-Novel.

Clarence objects, shortening the title to the published version. In the same vein, Carlton wants to add a little scrap

of Latin—alter et idem (one and the same

) and per multas aditum (through many paths

).

As a historical memoir, The New Purchase has had singular value as a narration of the early years of the institution by a main historical actor. But the fictive names of individuals and places, and the lack of a dependable chronology of events, have created interpretive problems. Evidently, Hall was determined to publish an account where the line between fact and fiction was vague, one that contained accurate descriptions of the places and people he encountered during his sojourn on the frontier of settlement but also infused with his private opinions and feelings. Perhaps he took this literary approach in order to process and redeem his young adulthood—and to protect himself from potential charges of libel. At its publication, The New Purchase was read as an account of pioneer life in Indiana. For the people of Bloomington, it also contained a fascinating account of the early operation of the seminary and college, still less than two decades old. Some in Bloomington were scandalized by Hall’s airing of the college’s dirty laundry; others might have been secretly gratified. In the eastern market, the book sold well, and the initial run of one thousand copies eventually sold out.

2.2 An Urtext

In The New Purchase, Hall described the situation that led to his eventual termination. The three faculty members—Hall, Harney, and Wylie—shared much in common, including an allegiance to the Presbyterian faith and a belief in the power of classical education. Harney and Hall were more traditional, however, and hewed to the method of rote learning, whereas Wylie was more open to expanding the classical curriculum. They also differed on questions of managerial authority and student discipline. With the coming of Wylie, who was older and had more administrative experience, battle lines soon emerged.

For the nearly four years of the seminary’s operation, Hall and Harney had accomplished the simple administrative tasks required. However, after the infant institution became a college, Wylie came in as president (fleeing an untenable situation at Washington College in western Pennsylvania) and took over administration. Complicating matters, Wylie brought several students along with him, and friction developed between students already in residence—so-called natives

—and the Pennsylvania transfers, termed foreigners.

In keeping with his satirical intent, Hall invented the name Bloduplex

for Wylie, to signify a person that could blow hot and cold with the same breath,

and introduced him with a rhetorical flourish: We now introduce a very uncommon personage, a most powerful prodigious great man, the first of the sort beheld in the New Purchase—the very Reverend Constant Bloduplex, D.D.—in all the unfathomable depths of those mystic letters.

10

In describing Wylie’s scholarly accomplishments, Hall wrote:

His talents were good; his acquirements respectable especially in Classics, Antiquities, History, and Literature in general; —still they were not uncommon. In Mathematics and Sciences, we cannot state his attainments; and simply because we never discovered them—yet he must have gotten beyond arithmetic, since Clarence [Hall], in return for aid in Greek, did gratefully assist the Doctor in Algebra. Harwood [Harney], indeed, thought the President’s attainments in such matters inconsiderable; but then Harwood was Professor of Mathematics and may have expected too much. At all events the President set no great value on these matters, making himself merry at Clarence’s expense, on accidentally discovering that this gentleman was studying Mathematics under the guidance of his friend Harwood, while Harwood read Latin and Greek with Clarence.11

Underscoring Wylie’s exaggerated portrait, Hall explicitly stated: We must say that Bloduplex is really a fictitious character!

12

Hall went on to analyze the character of the president:

As a companion, no man could be more agreeable than our President. It was this led our young Professors to unbosom [sic] in his presence—and even when, in an unguarded moment, the President remarked—proton pseudos, to imagine all sorts of wickedness and chicanery in all others; and then to combat all with such weapons as he fancied they were using or would use against him!13

The verbal portrait was not all negative: Doctor B. was an excellent preacher, and a still better lecturer, whether is regarded the matter or the manner: and some of his pulpit exhibitions were surpassingly fine.

14 Admiring his adroitness in ecclesiastical combats,

Hall explained that Wylie’s success was due to his Phrenological organization.

15 My own opinion is, President B. owed most of his victories—and some of his defeats—to his Wonderful Religious Experience! which in the stereotyped crying places always when first heard inclined weak believers to his side!

But upon repetition, most people saw through the act, the narrator averred.16

Alter ego professor Clarence analyzes why the president dislikes the professors, enumerating a list of probable reasons:

1. His jealousy of equals, and suspicious and untrustful temper: 2. His determination for a very low grade of studies—especially in Mathematics, and even in Classics,—he being resolved to level down and not up: 3. His love of ease, and wish to get along with a relaxed, or rather no discipline: 4. His using discipline as an instrument of avenging himself on students disliked by him: 5. His domineering and tyrannical temper: 6. His prying disposition, by which he was led to have spies in the professors’ classes, and to watch when they came and went to and from duties. &c.: 7. His desire to make room for former pupils and relatives: 8. His erroneous theology.

Summarizing the list of grievances, the text continues:

Hence, without consulting his peers, nay, contrary to their known wishes and earnest remonstrances, he tried to discipline students at will and to suspend and dismiss; he permitted some to be graduated, and who now hold imperfect diplomas, signed with his sole name: and he commanded what the Professors should and should not do, and what teach, and how, answering their arguments with insult and derision, and threatening to stamp them and the trustees also under his feet! He pretended to think, and dared to assert, that the discipline of a College was of right a President’s special duty, —and teaching, the Professors’. And, therefore, he rudely, on several occasions, contradicted his Faculty in public, and aimed to consider and treat them as boys!17

Continuing in the same vein, Hall ended the section with speculation about the president’s motivations, including the possibility of mental illness. In addition to criticism of Wylie, the text describes the organization and operation of the seminary, which became increasingly valuable historical source material.

After he introduced the major characters, Hall narrated a mystery that was the proximate cause that led to his termination: In his recitation room before class, Hall found an unsigned letter tucked into his pocket edition of Virgil and read it. It accused him of being an indolent and ineffective teacher and advised the professor to resign. The letter was sealed with wax that bore the imprint of Wylie’s desk key, so Hall naturally thought that the president was the author. His colleague Harney and his wife, Mary Ann, agreed with that surmise after they read the letter. They compared older letters written by Wylie for corroboration and discovered the most remarkable similarity, as to the hand—the style—the words—the expressions—was apparent: nay, in some things, was an identity.

18

Harney advised Hall not to resign, however, without seeing President Wylie first. Hall described their meeting:

The letter was taken by the President, but not read all carefully and indignantly over, as by the others! And yet, at a glance, he learned all its items, and that so well, as to talk and comment on them! But still, after what he designed should pass for a searching scrutiny, in a moment he exclaimed,—

I know the hand writing—it is Smith’s!

How you relieve me, Doctor Bloduplex,said Clarence;Harwood was right to prevent me from sending in my resignation.—I shall continue—

Mr. Clarence,replied the President,Smith, I know, is your bitter enemy; and I am told you have many more, and especially among the young gentlemen that came with me: now, this shows a state of great unpopularity, and I do candidly advise, all things considered, that you had better resign!!

Doctor, pardon me, my first belief is returned—I know the author of this letter, and it is not Smith.

Later in the passage, Hall shared his strong impression that Wylie wrote the letter:

Dr. Bloduplex, from my inmost soul I do hope you may remove my suspicion,—but I much fear that you yourself are the author of this letter!

I!—the author! how could you ever entertain so unjust a suspicion?

God grant, sir, it be unjust—but I will give you the grounds of my suspicion.

Name them, sir,—I am curious and patient.

Here Clarence went over all that the reader has been told, but to a much wider extent, and with many arguments and inferences not now narrated; and then spread out the Doctor’s own letters, to be compared with the anonymous one. Upon which the Doctor said:

Well, Mr. Clarence, there is no resemblance between them, or but very little.

But is there not some? Has not the writer tried to imitate your hand—your style—your very grammatical peculiarities?

It does, maybe, seem a little so—

It does, indeed, Doctor Bloduplex; and now look here!—the seal is stamped with the key of your desk!

Here the President coloured; of course in virtuous indignation and surprise at such roguery, and in some little confusion exclaimed:—

The wicked dogs! they have stolen the key of my desk!

Clarence was here affected to tears; that one the other day almost loved and trusted as a father could be by him no longer so regarded….

Only assure me, Doctor, on your word of honour and as a Christian that you did not do this base action, and even now will I burn this letter in this very fire—(it was a cold day)—before your face.

Mr. Clarence,said heI solemnly declare I did not write this letter; but stay, do not burn it—let me have it and I will try and find the writer.

Still mystified by the poisonous letter, Hall narrated both his disbelief and his surprising reaction:

Of course, then, the letter was not written by the Reverend Constant Bloduplex, d.d.—for he had the best right to know; and he said, solemnly, that it was not. Yet Clarence,

all things considered,did that very week send his resignation to Dr. Sylvan [trustee president David Maxwell]; offering, however, to remain till the meeting of the Board. At that the Board offered him nearly double salary to remain some months longer till a suitable successor could be found; to which proposal Clarence acceded.

This then is the story that Hall narrated in The New Purchase, in which he was the primary protagonist.

The next year, 1831–32, Hall continued teaching temporarily, and the mystery of the anonymous letter persisted. Harney became embroiled in public controversies with Wylie over student behavior. Things escalated so much that the two men were involved in a physical altercation in which Wylie pushed Harney off a log spanning a mudhole. Eventually Wylie convinced the board of trustees to terminate Harney for insubordination. So, at the end of the 1831–32 school year, the original two professors left, and the administration was faced with finding replacements. The author of the anonymous letter did not come forward, leaving a chasm of silence surrounding the initiatory event that triggered the termination of the original faculty.

2.3 A Complex Historiography

Most of what we know about the early history of the Indiana State Seminary and Indiana College derives from Hall’s account in The New Purchase. There are no extant sources that bear on Wylie’s or Harney’s reactions to Hall’s testimony in the book. Although Hall had ample motivation to tell his side of the story about his conflict with the president, there is little reason to believe that he exaggerated or made false claims about it. As a writer, Hall usually left clear evidence of the facts of the matter at hand and his interpretation of them. But his deliberate scrambling of chronology and his penchant for combining separate acts have left readers puzzled. What emerges in The New Purchase is a protagonist trying to integrate various aspects of his personality and come to grips with his young adulthood by narrating his personal experiences, including his emotional reactions.

In a figurative sense, taken as a metaphor for those pioneering times, The New Purchase is a tale of ambition, intrigue, and disenchantment. Each of the protagonists—Hall, Wylie, and Harney—attempted to gain purchase on new opportunities as the state of Indiana made halting steps toward public higher education. Although our perspective is obscured by the passage of nearly two centuries, each of these men, full of passion and hope, made their way to the frontier hamlet of Bloomington to shape an infant institution. The outcome of their contest for influence meant that their names are differentially remembered, but all of them acquired some return for their investment of time and energy.19

Using The New Purchase as an archival source for interpretations of IU’s past has generated a complex and interesting historiography. Although the college was expanded and renamed Indiana University in 1838, its history remained confined to oral tradition until Hall’s book was published in 1843. David Maxwell and Andrew Wylie continued their administrative service into the 1850s, although faculty turnover was high. The deaths of Wylie in 1851 and Maxwell in 1854 were blows to the institution, removing two key individual mainstays. Over time, the details of their accomplishments were obscured, and collective memory enshrined the two men as founding figures. Following the College Building fire in 1854, Hall published a revised edition of The New Purchase in 1855, omitting the invective against Wylie and with it some descriptions of the institution.

After his departure from Bloomington in 1832, Hall held a variety of teaching posts at small academies in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York, often in combination with serving local Presbyterian congregations. He had a remarkable career as an author, with six books published in the two decades between 1836 and 1855. As mentioned previously, the first, in 1836, was a Latin grammar textbook for the use of primary schools, academies, and colleges.

Seven years later, The New Purchase came out. It became his most successful book and, perhaps, his most personally gratifying.

His rate of publication then dramatically increased, with another three titles in seven years. In 1846, Hall published another blend of personal quasi-fictive narrative: Something for Every Body: Gleaned in the Old Purchase, from Fields Often Reaped. Using the same pseudonyms (Robert Carlton, Esq., and Reverend Charles Clarence) and a dialogue structure, the book was an exchange of letters between Hall’s twin alter egos, talking about how to live a godly life. Dixie Richardson, Hall’s biographer, called the book an exuberant exposition of Hall’s opinions and observations on numerous subjects: theology, medicine, capital punishment (a gallows at the edge of town indicates the community provides its citizens safety), temperance, contemporary trends (unlike Brooklyn writer Walt Whitman, Hall scoffs at phrenology) and in the process he added more of his own history.

20

Two years later, Hall published a nonfiction title, Teaching, a Science: The Teacher an Artist, in which he expressed his views on pedagogy, noting in the preface, This book is not an experiment, but an experience.

21 In 1852, riding the wave of interest created by the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Hall released Frank Freeman’s Barber Shop, a novel featuring both Black and white main characters.22

Upon publication of the revised edition of The New Purchase in 1855, Hall was coming to the end of a remarkable period of literary productivity. It had been a dozen years since its original publication, and New Albany, Indiana, publisher John Nunemacher stoked Hall’s hopes for a revival of interest in the work. After Wylie’s death in 1851, Hall felt it was unseemly to mention their conflict and so excised nearly 130 pages that gave details about the story, omitting much of the description of the state seminary and college.23 Illustrations were added, the subtitle was shortened to Early Years in the Far West,

and the original preface was replaced with a new one, written and signed by B. R. Hall, Author, Pro. Tem.

The frontispiece featured an engraved portrait of Hall, identified simply as The Author.

Never resisting a didactic opportunity, Hall translated the Latin quotations that appeared on the title page:

24 Appearing in a single volume, the second edition of The New Purchase did not attract many new purchasers interested in reading about frontier days in southern Indiana.Alter et idem

means,—pretty much of a muchness,

or in better Saxon—Six of one and half a dozen of the other.

[Per multas aditum sibi sæpe figuras repperit

means]—Being crafty he catches with guile.

And these are the freest translations we are at liberty to give.

On the first of January 1863, during the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. Hall was living in Brooklyn at the time, working at the Park Institute School and assisting with services at the Dutch Reformed Church. Later that month, Hall died a few days before his sixty-fifth birthday. His passing merited an obituary in the New York Times:

As an author, as well as a teacher, he gained a wide reputation. Dr. Hall was distinguished by high intellectual culture and refinement, by delightful conversational powers, to which an incessant current of humor lent animation and brilliancy, and to which the cordial kindness of his nature gave geniality. His life, influenced by the strongest religious convictions, as well as by inherent charity, was spent in labors of beneficence which were only interrupted by his final illness.

In addition to misspelling his middle name as Rust,

the obituary included a mischaracterization in the recitation of his positions: Pastor of a Church and President of a College in Bloomington, Ind. for some years.

25 The first IU professor passed into historical memory, joining the first president and the first trustees board president.

2.4 Gathering the Historical Catalog

In 1881, the IU Board of Trustees asked longtime professor Theophilus Wylie to prepare a written historical catalog

for the university. The university had been granting diplomas for a half century, and there was a felt need to summarize the history of the institution in a permanent document. Hired in 1837, Wylie was the seventh person appointed to the faculty; he was also Andrew Wylie’s cousin. Wylie started writing to alumni and former faculty to gather information. Trustee David Banta, a former judge and county historian, became president of the trustee board in 1882, and he also started writing to former members of the university’s academic community for information.26

Among the people Professor Wylie contacted was his relative Andrew Wylie Jr., the eldest son of the former president and an 1832 graduate of Indiana College. He served as a federal judge of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. Professor Wylie was seeking information about Judge Wylie’s father and inquired about the anonymous letter that Professor Hall referred to in The New Purchase: I have never thought it possible that he could have written it, & I would [inquire if?] you know certainly that & positively that it was not written by him, not as I know it [from?] being morally certain that he did not & could not have written it. Please inform me, so that from positive knowledge I might contradict it. I do not mean in the published catalogue, for I think it would be better to ignore all disagreeable things in such a publication.

27

Banta wrote to Matthew Campbell, a member of the class of 1834 and a former instructor in IU’s Preparatory Department, who replied in detail about his memories. Regarding the anonymous letter, he wrote, I know that Judge Wylie (who now strongly resembles his father tho’ he was nothing like him 50 years ago) w[oul]d acknowledge the anonymous letter as his own. And yet I judge he never so acknowledged it to his father. Ask him.

28

Unbeknownst to Campbell, Banta had received a letter from Judge Wylie a short time earlier, admitting that he was the author of the anonymous letter.

Washington Dec 17, 1882

D.D. Banta, Esq.Dear Sir: Your letter date 7th inst. was duly received and would have had earlier attention but for the pressure of official and other duties. The anonymous letter to which you refer was written by me without the knowledge, suggestion, remotest hint, or suspicion on the part of my Father. I was at that time a boy of sixteen years. The anonymous note to Mr. Hall contained no more than the almost universal opinion of the students. He was indolent, careless, superficial and shamefully neglectful of his duties. Both he and Mr. Harney had been professors in the college for several years previous to Father’s election as its first president, and were jealous of him, on that account, as well as for other obvious reasons. The letter was the deed of a boy, a small affair, and ought to have been so regarded. Mr. Hall & Mr. Harney, however, declared that it was my Father’s hand, disguised, would accept no denial, would hear no explanation, and refused consent that an investigation should be made by the faculty. Father offered to have every student examined, on honor, and pledged himself that whoever should be found to have written the letter he should be expelled. Hall & Harney declined to have the investigation made, but continued to circulate this false charge throughout the state, along with others equally unfounded. Father became indignant, and thenceforth treated them as personal enemies and wilful [sic] slanderers. It was an ill considered [sic] thing on my part to write such a letter, but every word of it was true, and I had no idea that it was to create so much trouble. After the trouble was created[,] I felt impelled to come out and avow its authorship, but was restrained from so doing, by the consideration that such an avowal would be used by H. & H. as proof that their charge was substantially true, and that the letter, if not written by the hand of Dr. Wylie, was written by his son, at his dictation; and I retained the secret for years afterwards, even from my Father. I do not now pretend to claim that my conduct in this respect was either wise or brave. A man of mature mind and experience would have adopted the other course. I do not know whether or not my Father even ever prepared such a written account of the matter as that you refer to: I never saw, or heard of it, if he did. I have always regarded, as do now look upon the affair as beneath the serious consideration of sensible people, except for the slander to which it gave rise to and the annoyance it gave to my Father, whose nature revolted at the suggestion of a meanness and was ever at warfare with all sorts of pretenders and rascals.

[Signed]

Andrew Wylie

With the letter in hand, Banta confirmed the identity of the anonymous writer of the letter that had led to Hall’s termination a half century before. Surviving records do not tell whether he shared the knowledge with Theophilus Wylie and other individuals, but he suppressed the information when he prepared a speech on The Faculty War

presented ten years later.

In mid-July 1883, amid a driving rainstorm, Indiana University suffered another calamity as Science Hall was struck by lightning and consumed by the resulting fire. Science Hall housed IU’s extensive scientific collections, including the Owen Cabinet of natural history and Professor David Jordan’s fish specimens, as well as the library and administrative records—nearly all of which was destroyed. Unlike the 1854 campus fire, it did not cripple the university, but it was the proximate cause of relocating operations to a more commodious site on the eastern outskirts of Bloomington. About a year later, a new president was chosen. The new Dunn’s Woods campus was ready in 1885, presided over by the former biology professor Jordan, who oversaw major changes in the curriculum that accompanied the move.

The loss of another tranche of university records made the historical catalog project more difficult but increased motivation for its completion. Professor Wylie and trustee president Banta continued to push forward in the tedious gathering of data from the alumni body. Wylie reached emeritus status in 1886, and though now in his mid-seventies, he remained dogged in his pursuit of the project. Banta was working closely with the new president, Jordan, making pleas for more state support and trying to improve the university. An important way to document the past, the historical catalog was seen as a necessary background to the current revivification, which added the promotion of research to the existing goals of equipping students with useful skills in the context of liberal arts education.

While research continued for the historical catalog, in 1889 President Jordan announced a day dedicated to the founders of IU—called Foundation Day. Its centerpiece was a historical address by Banta, who soon would retire as trustee president to take up the deanship of the IU School of Law. In keeping with the oral tradition and hewing to the storyline promoted by David Maxwell, the inaugural leader of the trustees, Banta started with The Seminary Period (1820–1828),

which dealt with the state’s first effort to provide higher education.29 Reading from a text prepared for the occasion, he described the legislative history of the Indiana State Seminary of learning and its first instructor:

While the General Assembly was legislating the seminary into existence, a young man, destined to be its first professor and to stay with it through its seminary life, and to be with it when it passed up into the Indiana College, and finally to leave that college a disappointed and embittered man and write a book maligning his enemies and making sport of his friends, was taking his last year’s course of lectures at Union College, under the celebrated Dr. Nott. This young man was Baynard R. Hall. After receiving his first degree at the commencement of 1820 at Union, he went to Princeton where he studied theology, after which he was ordained a minister of the Presbyterian church. Returning to Philadelphia, his natal city, at the close of his theological studies, he married and soon after set out with his bride for the New Purchase.30

Banta mentioned Hall several times during his speech and used information derived from The New Purchase, sometimes without attribution. He also speculated, without evidence, that Hall came to Indiana because of the seminary.

On the following Foundation Day, in 1890, Banta continued with the early history of the institution, From Seminary to College (1826–1829).

He detailed its legislative history and the coming of Andrew Wylie as its inaugural president. Members of the class of ’90 presented Scenes from the New Purchase, an original play adapted from The New Purchase. Composed of four scenes depicting Hall’s sojourn: travel from Louisville to Bloomington, his hiring by the board of trustees, the first meeting of the first class, and the protest over Harney’s religious faith (Presbyterian) being the same as Hall’s. The play featured handmade costumes, and a prologue read by Samuel B. Harding, a history professor.31

The historical catalog, titled Indiana University, Its History from 1820, when Founded, to 1890, was finally ready for publication in 1890. Banta contributed the chapter The Indiana Seminary,

which was shortened from his Foundation Day address. In it, he described the first professor:

The choice could hardly have fallen upon a worthier man. His academic education he had received at Union College and his theological at Princeton. He was an excellent classical scholar and a persuasive and sometime eloquent preacher. As a teacher he was enthusiastic, faithful and painstaking. Into the frontier life of the White River settlement, in which his lot was cast for a time after he first came to the State, he entered with a zeal that soon brought him to know all its peculiarities, a knowledge that stood him many a good turn while at the head of the State seminary.32

Banta described the frontier skills Hall acquired and his interest in pioneer ways.

Two years later, in 1892, Banta presented his fourth Foundation Day address, entitled The

33 He described the main protagonists—President Andrew Wylie, Professor Baynard Hall, and Professor John Harney—and concluded with a summary of their characters: Faculty War

of 1832.Men admired the tall, graceful, grave, stately-stepping, and dignified Wylie. Men loved the blue-eyed, jolly, laughing, easy-going Hall. Men feared the erect, precise, nervous, heavy-jawed, firmly-stepping, neatly dressed, military-looking Harney.

34

Banta went on to narrate a key element of the story—the anonymous letter: Some time toward the close of the collegiate year of 1830–1831, probably in September—which was nearly two years after Dr. Wylie came—Professor Hall found in his

35pocket Virgil, left as usual on the mantel of his recitation room,

an anonymous letter, which taxed him the very plain language with the same charges current among the foreign

students—incompetency and neglect of duty—and demanded his resignation.

Hall was convinced that Wylie wrote the letter, and his colleague Harney agreed, but Wylie solemnly and indignantly denied its authorship.

36 Banta stated unequivocally, And yet Dr. Wylie did not write that letter. It was written by a Pennsylvania student,

37 Banta quoted Hall’s account of his resignation in The New Purchase but went on to discuss Hall’s actual letter, which he saw as part of the without,

as he himself says, the knowledge, suggestion, remotest hint or suspicion

on the part of Dr. Wylie.old record

that was destroyed by the 1883 campus fire and in which Hall cited dissatisfaction.38

For his general storyline, Banta depended on the description of the episode in The New Purchase, even quoting the book without citation, but augmented by his inquiries the decade before. He did not reveal the plain truth that the junior Andrew Wylie, now a federal judge, had written the letter, only that a Pennsylvania student

was the author. Obliquely, he did disclose Matthew Campbell’s understanding that Wylie, a fellow classmate in the 1830s, was the writer.39

Thus, Banta’s narrative became the latest writing on the subject, incorporating Hall’s 1843 account but providing a new interpretation that emphasized its effect on the university. Judging that neither side was without fault,

he eschewed assigning blame but concluded their personal controversy worked a grievous wrong to the institution.

40 This rewriting of institutional history obliterated Hall’s original motivation by incorporating his account for new purposes.41

2.5 Into the Twentieth Century

In 1902, the Indianapolis News published a retrospective review of The New Purchase with fresh insight into its historical value:

As a volume curiously expository of early Indiana, it is also a volume curiously expository of Dr. Baynard Rush Hall. Regarded as a literary boomerang, the printed word far outranks the pen or the sword….To the painful surprise of Dr. Hall and his New Albany publishers, the new edition of

The New Purchasecreated no furor in the book world, East or West. The book, however, sold slowly for almost half a century; and now a copy of the 1855 edition is almost as unobtainable and as great a book curio as one dated 1843. With all its faults, and in spite of Indiana’s resentment of its unjust caricature, the human interest ofThe New Purchasewill long maintain it, as Dr. Hall pronounced it, anIndiana classic.42

With no mention of its role as an early account of the origins of Indiana University, the review underscored its value in American literary and social history.

In 1913, IU historian James Woodburn published a commentary on The New Purchase, inaugurating another phase in its literary historiography. Appearing in the Indiana Magazine of History, it was an address prepared for the History Society of Wabash College and was also read before other county history groups. Woodburn emphasized Hall’s connection to the new state seminary and his literary ambitions before launching into a review of frontier life as depicted in the volume. He spoke about Hall’s descriptions of native speech patterns, social life, amusements, and politics, among other topics. Despite the presence of the benighted and the indifferent,

Woodburn spoke about the pioneer spirit that Hall brought to life: But let us remember that among the rank and file of struggling Hoosiers in the new commonwealth there were others who hailed the prophecy and the promise of a better day; who gave of their toil and meagre substance to truth, to religion, to learning and education, and who were ready to dedicate to the upbuilding and higher intelligence of their State, their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honors.

43 In keeping with Woodburn’s professional commitments, he advised the audience of students and residents in his conclusion: One of the uses of history is to remind us not only of our unpaid obligation to the past, but of our never-ending obligation to the future.

44

As IU enrollments had grown steadily since the late nineteenth century, the ranks of alumni had followed suit. To increase communication with that constituency, the Indiana University Alumni Quarterly was launched in 1914. It contained a mix of university news items, feature articles, and alumni notes. It soon became the journal of record for contributions to IU history, with the help of Professor Woodburn and the editor, Ivy Chamness. Banta’s annual addresses on Foundation Day, presented from 1889 to 1894, were published in the first six issues of the Alumni Quarterly, including The Seminary Period

and The

further disseminating his version of the story.45 Woodburn followed with eight articles, published from 1915 to 1917, dealing with the university’s history from 1840 to 1860.46Faculty War

of 1832,

Meanwhile, Professor Woodburn convinced Princeton University Press to republish the 1843 edition of The New Purchase, long since out of print, as a contribution to the 1916 centennial commemoration of Indiana’s statehood. Woodburn wrote an introduction to the volume and some explanatory footnotes. He enthused, This work has been pronounced

adding, one of the best books ever written concerning life in the West,

There is certainly no more valuable book on early Indiana.

Woodburn quoted his erstwhile colleague Banta, who praised it as the best and truest history of pioneer life and pioneer surroundings in Indiana that can anywhere be found. Hall evidently entered with zest into the life and scenes about him, and he writes graphically of all he sees and hears.

47

In his discussion of the book’s publishing history, Woodburn noted that the 1855 revised edition omitted 130 pages, including mention of Hall’s conflict with Wylie. In the interests of historical completeness, the decision to republish the original 1843 version was made, college quarrel, personalities and all, without change or expurgation,

the editor explained.48 Woodburn concluded his paean to The New Purchase and its author: The general truthfulness of the book, the integrity and sincerity of its author and the great value to history of Hall’s descriptions and portraitures are now recognized by all and I do not hesitate to say that his book will ever remain what Hall richly deserved that it should prove to be, an imperishable Indiana classic.

49

Woodburn’s edition, with a valuable key to characters and places, became a standard. It was reviewed by at least eight periodicals, ranging from Boston’s Transcript to the Times Literary Supplement. Woodburn read the introduction at the 1916 annual meeting of the Ohio Valley Historical Association.50 The Indiana Magazine of History soon published a review of Woodburn’s edition of The New Purchase:

There is only one sufficient argument for a new edition of the story, but that argument is enough. As a picture of pioneer life in Indiana it is unequalled, and must necessarily always remain so. Mr. Hall qualified for writing the story by entering fully into the pioneer life around him. He saw and was broad-minded enough to appreciate the sterling character of the settlers. He was also frank enough to point out the unattractive features. The picture is not a burst of sunlight on the snow but a mixture of light and shadow, the light tempered with humor and the shadow tempered with sympathy.

The only criticism was that the author’s notes were mixed in with the editor’s notes.51

Meanwhile, one of Woodburn’s IU colleagues, Logan Esarey, published his massive two-volume History of Indiana in 1915. Encyclopedic in scope, the publication reviews the literature of the state, identifying Hall as the author of a penetrating study of early Indiana. In a concise summary, Esarey wrote: The lure of the West was in his blood. He had visions of doing great deeds for humanity in this land of miracles. He followed this dream, about 1822, into the wilderness of Indiana, locating on the frontier near the present town of Gosport. His book, The New Purchase, or Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, narrates his experiences there and at Bloomington. As a critical study of the pioneers it stands without a rival.

52 He quoted David Banta’s 1888 assessment that it was the best and truest history of pioneer life and pioneer surroundings in Indiana that can anywhere be found.

Harking back to the contemporaneous New Harmony experiment, Esarey concluded on an elegiac note: Nevertheless, like Robert Owen, Hall was unable to realize his beautiful vision and returned a disappointed man.

53

2.6 The Lincoln Inquiry

In the 1920s, The New Purchase came under fire precisely because of its catholic treatment of all sectors of frontier society. The Southwestern Indiana Historical Society, formed in 1920, had an ongoing Lincoln Inquiry,

seeking to establish the salience of Abraham Lincoln’s life in southern Indiana from 1816 to 1830. In 1923, at a luncheon meeting of the society, President John Iglehart explained the aim of the research program on Lincoln’s formative years in southern Indiana: Since American democracy was not of New England or of Atlantic Coast civilization, but was born in the northwest territory, the history of pioneer Indiana assumes a new importance; particularly because of its effect on Lincoln.

54 But the history of the people of southern Indiana has never been written,

he lamented.

Iglehart cited sources of literature that contributed to the historical image of Indiana, complaining that they presented a skewed picture because they did not focus on the better class of people.

55 He singled out for criticism The New Purchase by Hall, freshly available in the Woodburn edition. Rather than providing a new perspective, he cited the old criticism mounted by the Indianapolis Sentinel nearly seventy years previously in its review of the 1855 edition: The original design of the work was principally to hold up to public indignation and ridicule the late Rev. Dr. Wylie, president of the University, with whom the author has a disagreement, which led to his leaving the college, and also the late Governor Whitcomb, General Lowe, and others.

56

Iglehart claimed that the book breathes a contempt for western character

and that Hall was unable to adjust to himself to pioneer life and to become a part of it.

Iglehart continued to make assertions that were unsupported by evidence in Hall’s biography or the book:

The eastern states opposed the addition of new states to the Union, and there existed a fear of the development of an agricultural democracy on account of which theological students like Hall came West in part to preserve the religious and intellectual status quo of these older states. Such a thing was impossible and therefore Hall failed. Hall was wrecked on the shoals which even today confront every eastern man who for the first time comes West as a minister or teacher among western people—shoals which a tactless and narrow-minded man cannot successfully navigate. It cannot be denied that his viewpoint of the people is that of a leading actor in the play of early Indiana life where he failed to succeed and he makes no effort to disguise his bitterness as a bad loser.57

Iglehart also put forward another specious claim, regarding the circumstances of Hall’s termination from Indiana College nearly a century earlier: It was libelous in the extreme, full of express malice against leading men more successful than Hall was, who, upon the facts shown in the book, could do nothing less than discharge as teacher.

58 Apparently, Iglehart objected to Hall’s slice-of-life approach, which was inclusive of all classes in pioneer life and made copious use of colloquial expressions.59

After retiring in 1924, James Woodburn moved to Ann Arbor with his wife. He remained in touch with the IU administration, headed by his old friend President William Lowe Bryan, who encouraged him to continue his work in IU history. In 1936, Woodburn authored an entry for Baynard Rush Hall in the Dictionary of American Biography.60 In 1940, he published History of Indiana University: Volume I, 1820–1902.61 With no overarching storyline or integrated approach, the contents represent three distinct periods of composition. The first six chapters were written by David Banta, forming the text of his 1890s Foundation Day addresses about the early history of the institution, reprinted from their original publications in the Alumni Quarterly in 1914 and 1915. Next were eight chapters authored by Woodburn dealing with the university in the 1840s and 1850s, republished from issues of the Alumni Quarterly dating between 1915 and 1917. The last eight chapters were composed by Woodburn in the 1930s and display a mix of institutional history peppered with personal anecdotes.

The Woodburn volume became an extremely valuable reference to IU’s past, displaying stories of IU’s nineteenth-century existence filtered through the lens of two alumni authors (Woodburn and Banta) who were also faculty members. That authorship also accounts for some of the volume’s shortcomings, including the lack of overarching themes, the favoring of description over analysis, and the shortage of critical or comparative perspectives. The book also highlighted the dearth of primary source materials due to the campus fires of 1854 and 1883. Woodburn, who might have been aware of Andrew Wylie Junior’s instigating role in the removal of Baynard Hall, chose not to reveal that secret and published Banta’s 1892 account of the faculty war

of 1832 without amendment.

In the 1940s, literary analysts rediscovered Baynard Hall and The New Purchase, especially in the context of review articles and bibliography. Discussing early literary developments in Indiana, Agnes Murray noted that settlement patterns northward from the Ohio River confined literary production before 1850: Baynard Rush Hall’s New Purchase was the sole distinguished work written in the newer area of southern Indiana.

62 Robert Hubach, in a review of nineteenth-century literary visitors to Indiana, highlighted Hall’s sojourn in the new Hoosier state: One authority states that it stands unrivaled as a critical study of the pioneers,

with a footnote citing Banta’s earlier judgment.63

As IU expanded because of the Second World War, a great building program was launched, including student residence centers. In searching for appropriate names, the university decided to cull from the ranks of early trustees, students, and faculty members. Thus, in 1949, Baynard Hall’s name graced a small unit—Hall House—of the Joseph A. Wright Quadrangle.64

In 1950, IU history professor R. Carlyle Buley, in his Pulitzer Prize–winning study The Old Northwest, gave an insightful description about the author of The New Purchase, which Buley called a unique study of pioneer life in and around a college town

:

Hall has been criticized for a condescending and supercilious attitude and, at times, biting pen, but considering that this Easterner with a classical-theological education was dumped into the middle of the backwoods to teach Latin and Greek, that he found himself more or less accidently embroiled in an academic-theological imbroglio, it is rather to be wondered at that his treatment of persons and life was as sympathetic as it was. It is not necessary to read between the lines to detect that Hall came to like the surroundings and people more than he, himself, may have realized; at any rate he delivered himself

right smartamount of firsthand material. His book, along with Mrs. Kirkland’s, would be on any list of a half dozen necessary for a picture of the life of the period.65

In the late 1950s, the multivolume Bibliography of American Literature contained a directory featuring nearly 300 authors of significance in American literature. Hall was among the authors included, and The New Purchase and several other works were mentioned.66

As a biographical subject, Hall emerged again in 1966, during the Indiana sesquicentennial year. Brief excerpts from The New Purchase were published in the Indiana Magazine of History, introduced by editor Donald Carmony, IU history professor, and assistant editor Herman J. Viola, a history doctoral student.67 In their brief commentary, Carmony and Viola noted Hall’s affiliation with the state seminary and his vivid descriptions of pioneer life.

Four years later, Hall’s institutional career was discussed in Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer by Thomas D. Clark.68 A respected University of Kentucky historian, Clark had an extended appointment at IU as a visiting professor to research and write a new history of the institution for its 1970 sesquicentennial. Hewing to the existing historiography, Clark did not break new ground with his narrative of the Indiana State Seminary of learning and the contretemps that led to the discharge of its original faculty members in 1832. He noted, however, Hall was to have an enduring say. In The New Purchase he detailed the quarrel with genuine discredit to Wylie.

69 Clark suggested the root of the problem lay in different approaches to teaching, with Wylie less wedded to rote learning than Hall or Harney.

2.7 More Recent Scholarship

Scholars of literature and language continued to find The New Purchase useful. In 1983, Hall merited an entry in the Oxford Companion to American Literature, now in its fifth revision but still under the editorship of James Hart, who first assembled the compendium in 1941. The brief entry mentioned The New Purchase (1843) and Frank Freeman’s Barber Shop (1852).70 In 1985, the Dictionary of American Regional English cited The New Purchase a total of 353 times.71 As Hall’s book aged, it found new importance as a historical source to reconstruct pioneer life in southern Indiana as well as linguistic patterns in the Hoosier dialect.

In 2004, Thomas Conway sought to explore the culture of early Indiana, from 1816 to 1830, when Abraham Lincoln was a boy. He stated, Perhaps the best source of Hoosier culture was a novel, The New Purchase, written in 1843 by Baynard Rush Hall under the pseudonym of Robert Carlton. Hall arrived in southern Indiana in 1823 and left the year after Lincoln did.

72 Conway admired Hall’s sharply observant eye

in discerning the ethos and charm of the pioneers who settled in the

so different from other areas of settlement:Big Woods,

What was fascinating, especially to sensitive outsiders like Hall, was that a distinct culture had evolved, unlike the world of eastern rustics. Although it was unlikely that he would ever meet the young Lincoln, he did meet and also describe Lincoln-like prototypes. Undoubtedly, since Lincoln was a Hoosier, the language that he spoke among his family and friends was the dialect of the community in which he and his ancestors had grown. Such people had their distinct vocabulary and modified values. This is what Hall discovered and about which he wrote.73

The article goes on to discuss the lost language

of frontier people and problems of historical interpretation. Conway noted that Hall frankly liked the frontier types he describes, and he tried to become a member of their community,

unlike other accounts that patronized or caricatured early Hoosiers.74 He summarized, Perhaps the stellar work of its genre, Hall’s fictionalized memoir of his years in pioneer southern Indiana is the most outstanding source for the culture and, especially, the idiom of the American Backcountry folk.

75 The literary historiography of The New Purchase, at least in studies of American language, had moved considerably from the defensive reactions of the Lincoln Inquiry of the 1920s.

In 2009, journalist and genealogist Dixie Kline Richardson published a biographical study, Baynard Rush Hall: His Story.76 Decades after an early encounter with The New Purchase, she was determined to set the record straight

because the man and the book have been misunderstood, misjudged, and misread.

77 This unlikely champion presented a detailed reading of Hall’s life, with critical yet sympathetic insight, and established a helpful personal and family context. Richardson’s close reading of archival sources led to the 1882 letter of Andrew Wylie Jr. to trustee president David Banta and disclosed the rest of the story of the faculty war

that Banta had hidden in 1892.78

In 2012, historian Keith Erekson examined the Lincoln Inquiry conducted by the Southwestern Indiana Historical Society in the 1920s and 1930s. Citing the criticism originally leveled by John Iglehart against Baynard Hall and his book nearly a century before, Erekson paraphrased Iglehart’s opinion:

Society workers contended with more widely read novels—in particular Baynard Rush Hall’s The New Purchase (1843) and Edward Eggleston’s The Hoosier Schoolmaster. Hall came to Indiana from Philadelphia to teach at the seminary in Bloomington (later Indiana University). When the school passed him over for the position of president, he responded first by feuding with school officials and then by returning to the East, where he wrote a thinly veiled memoir that castigated his former neighbors. Iglehart branded the book

cowardly libelbecause itbreathes a contempt for western characterand because the authormakes no effort to disguise his bitterness as a bad loser.79

Erekson simply embellished Iglehart’s unsupported assumptions about why Hall composed The New Purchase and ignored other contemporary views, such as Logan Esarey’s, which praised Hall’s book.80

2.8 Conclusion

An irony persists at the heart of Baynard Hall’s career at Indiana College. Were it not for Hall’s hard feelings and outrage directed toward President Wylie that motivated the writing of The New Purchase, we would not have his vivid descriptions of Bloomington and the early years of what became the state university. After Wylie died, Hall demonstrated a measure of charity and excised the criticism of the president in the revised edition of 1855—along with much of the material pertaining to the college. Luckily, when James Woodburn supervised the republication of The New Purchase in 1916, he went back to the original text. The narrative remains a monument of personal hurt transformed into literary art.

It was not until later generations that faculty publication became common and then expected of IU professors. With a half dozen books to his credit, Hall outstripped his Indiana contemporaries and most of his nineteenth-century successors. His posthumous reputation rests mainly on The New Purchase, an eyewitness account of what he saw, heard, and felt living in southern Indiana from 1824 to 1832. As the first historian of what became Indiana University, understanding his career as a historical figure as well as his historical perspective in all its complexity ought to make us grateful for his life as well as his narrative. We are still learning from Baynard Rush Hall.81

Baynard Rush (Robert Carlton, pseud.) Hall, The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, ed. J. A. Woodburn (1843; repr., Princeton University Press, 1916). The New Purchase referred to the 1818 acquisition by the United States of the central third of Indiana from the resident Miami tribe and others living in the territory in the Treaty of St. Mary’s, conducted in Ohio during September and October 1818. Monroe County and Bloomington were organized in 1818.↩︎

See Dixie Kline Richardson, Baynard Rush Hall: His Story (Indianapolis: Dixie Kline Richardson, 2009).↩︎

Baynard Rush Hall, Exercises, Analytical and Synthetical; Arranged for the New and Compendious Latin Grammar (Bedford: Harrison Hall, 1836); reviewed by Alfred Addis, “Latin Grammars,” The Literary and Theological Review 6, no. 21 (1839): 59–66.↩︎

Hall, The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, 1916.↩︎

The book was referred to as

quasi-fictive

by The Oxford Companion to American Literature in 1983.↩︎Hall, The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, 1916, xvii.↩︎

Hall, The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, 1916, 486–87. Proton pseudos refers to a wrong assumption or error in premise.↩︎

Hall, The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, 1916, 489.↩︎

One early example is found in Charles Blanchard, ed., Counties of Morgan, Monroe, and Brown, Indiana: Historical and Biographical (Chicago: F.A. Battey & Co., 1884), 478:

↩︎President Wylie’s connection with the college proved very advantageous, not only to that institution, but to Bloomington and Monroe County. He was famed for his learning all over the East and South, and soon students from distant States came to Bloomington to place themselves under his instruction. But the sudden and permanent popularity of President Wylie led to bitter jealousy on the part of Profs. Hall and Harney, who no doubt envied him his good fortune, and wished for the possession of his place and honors. The unpleasantness ceased with the permanent departure of Hall and Harney, in 1832. The college flourished greatly under the management of President Wylie, and its influence was soon felt upon the community.

Baynard Rush Hall, Teaching, a Science: The Teacher an Artist (New York: Baker; Scribner, 1848), v.↩︎

Baynard Rush Hall, Frank Freeman’s Barber Shop (New York: Scribner, 1852).↩︎

In correspondence about the second edition, Hall stated,

In the work here and there certain words and expressions that have caused me often much sorrow in remembrance, and I would have given many dollars if they could have been blotted out. And more especially there would be so manifest an unkindness in reprinting a vast amount of what pertains to the late President of a certain college, that I would nearly as soon consent to have a finger taken off as to continue that

(Baynard Rush Hall, “Letter to John Nunemacher,” May 13, 1855).Hall reminded Nunemacher that

all of the chapters and passages in the second volume relative to Dr. Bloduplex (President Wylie) are by all means to be discarded…. This gentleman richly deserved all that was done to him some years ago, but he is now in the other life, and I hope in a better one

(Hall; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: IV. The ‘Faculty War’ of 1832,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 4 (1914): 369–86)↩︎Baynard Rush Hall, The New Purchase; or, Early Years in the Far West, 2nd ed. (New Albany, IN: Jno. R. Nunemacher, 1855).↩︎

“Obituary: Baynard Rust [sic] Hall,” New York Times, January 27, 1863, 5.↩︎

D. D. Banta, A Historical Sketch of Johnson County, Indiana (Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co., 1881); William McCaslin and D. D. Banta, History of Johnson County, Indiana (Chicago: Brant & Fuller, 1888).↩︎

Theophilus Wylie, “Letter to Judge Andrew Wylie,” July 18, 1881. IUA/C202/B5/F Letters relating to history.↩︎

Matthew Campbell, “Letter to David Banta” (Indiana University Archives/C112/B1, December 25, 1882).↩︎

See Howard F. McMains, “The Indiana Seminary Charter of 1820,” Indiana Magazine of History 106 (2010): 356–80.↩︎

David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University I: The Seminary Period (1820–1828),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1914): 3–24, quote on 13.↩︎

See the description of the second staging of the play twenty-five years later, at the 1915 alumni reunion: “The 1915 Commencement,” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 3 (1915): 282, 286–87.↩︎

Theophilus A. Wylie, Indiana University, Its History from 1820, When Founded, to 1890, with Biographical Sketches of Its Presidents, Professor and Graduates, and a List of Its Students from 1820 to 1887 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1890), 38–46, quote on 43.↩︎

Banta, “History of Indiana University,” 1914; quote on 373. Republished in James A. Woodburn, History of Indiana University: Volume I, 1820–1902 (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1940), 78–97.↩︎

Woodburn, History of Indiana University, 1940, 82. They were all dead by that time, so he relied on other sources.↩︎

Woodburn, 85. Banta quoted from Andrew Wylie Jr.’s letter but did not identify him by name.↩︎

Banta described Campbell:

who was a student here at the time the letter was written, and who for forty years kept the secret of the writer.

Woodburn, 84.Forty years

probably refers to the publication of The New Purchase in 1843 and the 1882 receipt by Banta of letter from Andrew Wylie Jr. admitting authorship. That raises the intriguing questions of who else knew the secret in the 1830s, how it was spread following the 1882 letter, and why it remained hidden in the archival files for decades.↩︎Cf. Merton’s dictum,

obliteration by incorporation.

See Chapter 3.↩︎Emma Carleton, “About the New Purchase,” Indianapolis News, May 16, 1902, 10.↩︎

James A. Woodburn, “Local Life and Color in the New Purchase,” Indiana Magazine of History 9, no. 4 (1913): 215–33, quote on 233.↩︎

Banta, “History of Indiana University I”; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: II: From Seminary to College (1826–1829),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1914): 142–65; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: III: The New Departure (1829–1833),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 1, no. 3 (1914): 272–92; Banta, “History of Indiana University,” 1914; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: V: From College to University (1833–1838),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 1 (1915): 5–17; David D. Banta, “History of Indiana University: VI: Perils from Sectarian Controversies and the Constitutional Convention (1838–1850),” Indiana University Alumni Quarterly 2, no. 2 (1915): 99–110.↩︎

Hall, The New Purchase, or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West, 1916.↩︎

Hall, xii. Calling the conflict between Professor Hall and President Wylie the

college quarrel,

Woodburn eschewed Banta’swar

metaphor.↩︎James Albert Woodburn, “The New Purchase,” in Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Ohio Valley Historical Association, ed. Harlow Lindley, vol. 6, 1 (Indiana Historical Society Publications, 1916), 43–54.↩︎

“The New Purchase or Seven and Half Years in the Far West,” Indiana Magazine of History, n.d. unsigned review of Hall, The New Purchase (1916), quote on 354.↩︎

Logan Esarey, History of Indiana (Indianapolis: W. K. Stewart Co., 1915), 1112.↩︎

Esarey, History of Indiana. In a footnote, Esarey evaluated:

The volume does not rank high in literary merit, but the descriptions are vivid, faithful and historically just.

In 1919, another historian of Indiana, Jacob P. Dunn, published a massive multivolume compendium, Indiana and Indianans: A History of Aboriginal and Territorial Indiana and the Century of Statehood (Chicago and New York: American Historical Society, 1919), in which Hall’s career at the state seminary and college is briefly noted in volume two, pages 873–874.↩︎John E. Iglehart, “Correspondence Between Lincoln Historians and This Society,” in Proceedings of the Southwestern Indiana Historical Society, vol. 63–88, 18 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1923), quote on 64.↩︎

John Iglehart died in 1934. In her 1938 summary of the Lincoln Inquiry, Bess V. Ehrmann, The Missing Chapter in the Life of Abraham Lincoln (Chicago: Walter M. Hill, 1938), 17 does not mention The New Purchase by name but by implication when she criticizes

certain novels dealing with the uncouth, illiterate pioneers in the Hoosier state.

↩︎James A. Woodburn, “Baynard Rush Hall,” in Dictionary of American Biography, 1936.↩︎

Agnes M. Murray, “Early Literary Developments in Indiana,” Indiana Magazine of History 36 (1940): 327–33, quote on 331.↩︎

Robert R. Hubach, “Nineteenth-Century Literary Visitors to the Hoosier State: A Chapter in American Cultural History,” Indiana Magazine of History 45 (1949): 39–50, quote on 40.↩︎

Indiana University Board of Trustees, “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University, 21 October 1949–22 October 1949” (Bloomington: Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, October 21, 1949), https://purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/archives/iubot/1949-10-21.↩︎

R. Carlyle Buley, The Old Northwest: Pioneer Period, 1815–1840, vol. 2 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1950), 557.↩︎

Jacob Blanck, Bibliography of American Literature, vol. 3 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959), 341–43.↩︎

Baynard Rush Hall, Donald F. Carmony, and Herman J. Viola, “The New Purchase: Or, Seven and a Half Years in the Far West,” Indiana Magazine of History 62, no. 2 (1966): 101–20.↩︎

Thomas D. Clark, Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer: Volume I: The Early Years, 4 vols. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970).↩︎

James D. Hart, 5th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 307.↩︎

Frederic G. Cassidy, ed., Dictionary of American Regional English (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985).↩︎

Thomas G. Conway, “Finding America’s History,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 97, no. 2 (2004): 92–106, quote on 93.↩︎

Keith A. Erekson, Everybody’s History: Indiana’s Lincoln Inquiry and the Quest to Reclaim a President’s Past (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 26.↩︎

See discussion earlier about Esarey’s judgment of The New Purchase.↩︎

This essay has concentrated on Hall’s best-known book, The New Purchase, but scholars have paid attention to another work, Frank Freeman’s Barber Shop, a novel published in 1852 as a rejoinder to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. A mention in 1922 stated:

It is undoubtedly an important early study of the psychology of the Negro

(Jeannette Reed Tandy, “Pro-Slavery Propaganda in American Fiction of the Fifties,” South Atlantic Quarterly 21.1, no. 1 (January 1, 1922): 41–50, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-21-1-41; Jeannette Reed Tandy, “Pro-Slavery Propaganda in American Fiction of the Fifties,” South Atlantic Quarterly 21.2, no. 2 (April 1, 1922): 170–78, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-21-2-170; quote on 173). A reexamination was launched by Thomas A. Gossett in Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1985). More recent discussions include Joy Jordan-Lake, Whitewashing Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Nineteenth-Century Women Novelists Respond to Stowe (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005); Diane N. Capitani, Truthful Pictures: Slavery Ordained by God in the Domestic Sentimental Novel of the Nineteenth-Century South (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009); Erica Burleigh, Intimacy and Family in Early American Writing (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); and Sarah N. Roth, Gender and Race in Antebellum Popular Culture (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).↩︎