Chapter Eight

One day that fall, Lila arrived home from school and found her mother and Aunt Hattie sitting at the table. They were drinking tea and it looked like Hattie had been crying. Lila was surprised that they were together because her mother didn’t like Hattie very much. She didn’t think it was appropriate for a married woman to work outside the home. (Hattie was not fond of Hazel either, but the Slabacks were the only family she had in La Crosse.) Please go into the kitchen and peel the potatoes,

said her mother. Lila wanted to ask what was wrong, but she knew it would only make her mother angry. Uncle Frank joined them for dinner, but it was unusually quiet at the table. They talked about work and Izro and Myron—they were expecting their first child. Aunt Hattie had recently paid a visit to Myron’s mother.

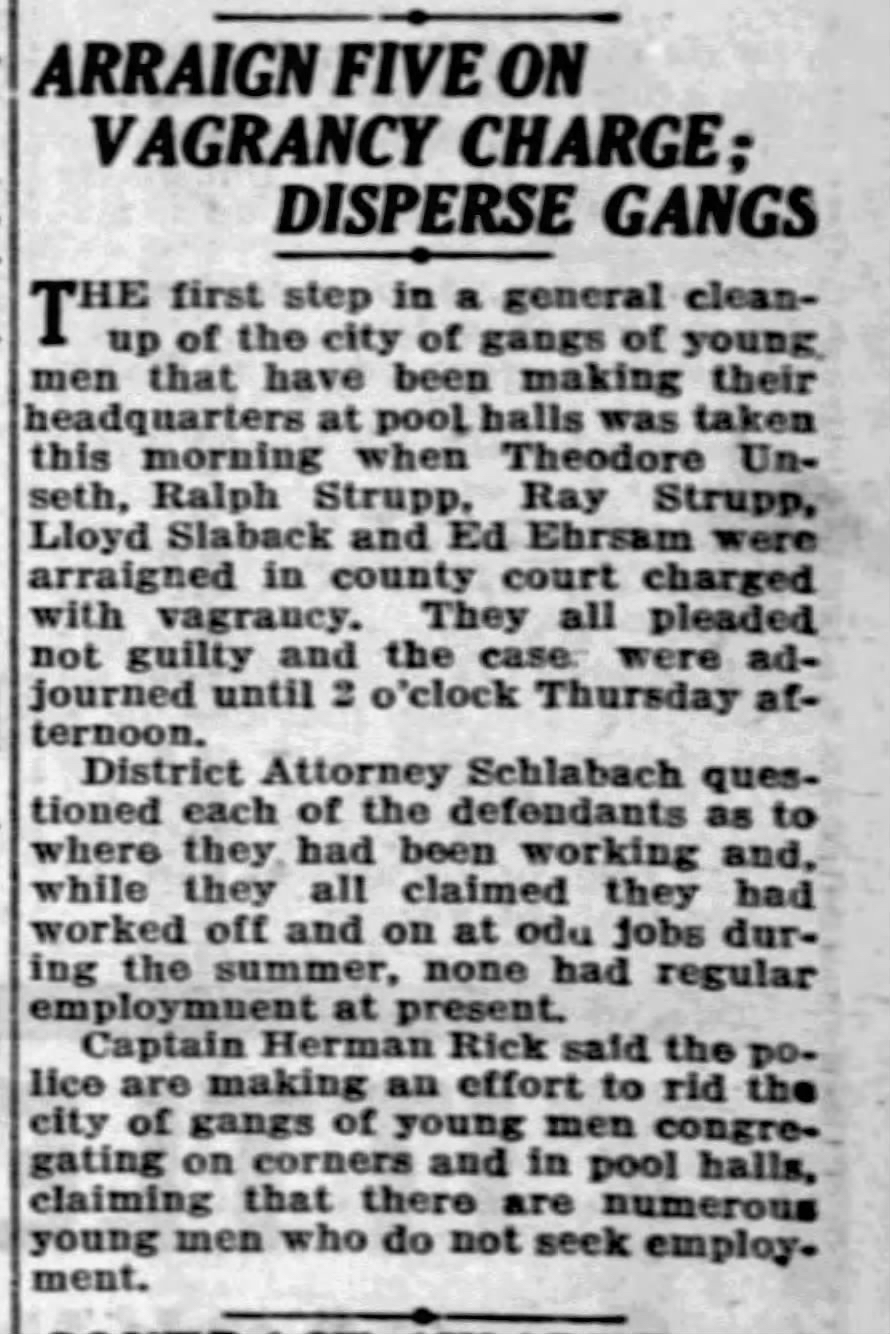

The next day when Veda was gathering rubbish from the house, she found a newspaper folded to an article with Lloyd’s name. She read it out loud to Lila. Lila was confused. Lloyd was working for her father…she had seen him at their house. She asked Veda, What is vagrancy?

Veda said she didn’t know, but it must be something bad if the police had arrested him. No wonder Aunt Hattie had been crying.

Lila was still wondering about Lloyd when a stranger knocked on the door one night during dinner.

Can I help you?

said her mother.

Yes, I’m here to collect information for the census.

She let the woman into the house and told Cecil to give up his seat.

The census taker said, This won’t take long, but if you don’t mind, I’ll sit with you and fill out the forms while you eat.

She sat down next to Lila and opened her book to a page that was nearly full of the most beautiful handwriting, even nicer than Veda’s. Mr. Slaback, is it? Could you kindly tell me your full name and your relationships to these lovely young men and women?

She had so many questions about their names and ages, the value of their house, where their parents had been born, and who was attending school. She asked the children to raise their hands if they could read. Lila raised her hand with pride. This was fun!

At the end, she asked Lila’s father if he was employed and to describe his line of work.

He said, Yes, I’m working. I do odd jobs around the neighborhood.

What? Suddenly, Lila felt sick to her stomach. She remembered the article about Lloyd; in the courtroom, he had claimed to be doing odd jobs.

Was her father going to be arrested too? Lyle was working for her father’s plastering business, but she noticed that the census taker had recorded him as being in school.

Lila said nothing and looked around the table. Her mother and father did not seem concerned and did not correct the census taker’s mistake. Lila was relieved when the woman thanked them and stood up to leave. Her mother followed her to the door and said, Have a nice evening.

There were plenty of good jobs available in La Crosse—at the rubber mill, the iron foundry, the tobacco works, the MotoMeter factory, the railroad—but John Slaback chafed at working for other people. He didn’t want to farm, but he didn’t want other people telling him what to do. His views on work boiled down to one statement: My ancestors didn’t come to this country to be slaves to the rich.

His brother Elmer had taught him how to plaster houses. It was satisfying work but unpredictable. Sometimes, he would be so busy that Lila would barely see him for weeks. At other times, there was barely any work, and their budget would be stretched razor-thin. It was dangerous to ask for anything during the lean times.

That night in bed, Lila asked Veda if their father was going to be arrested for doing odd jobs.

No, silly! Why would you ask that?

Lila recounted how Lloyd had been doing odd jobs

when he was arrested by the police, but the newspaper said he was unemployed.

Lloyd should be getting married instead of drinking and playing pool; Daddy has been married for a long time.

Lila was not entirely convinced. After a few minutes of letting the matter swirl in her mind (what was pool,

and why did it matter if he was married?), she decided to trust her older sister’s wisdom and quickly fell asleep.

Notes

Slaback is not a very common name, so it was not too difficult for me to find family members in databases of historic newspapers. This project helped me learn how I’m related to every Slaback in La Crosse, Wisconsin. The two family members mentioned in the newspaper most often were Aunt Hattie (aspiring socialite) and her youngest son, Lloyd, who spent most of his adult life in and out of prison; I imagine the negative press was devastating to Aunt Hattie.

A distant relative that I connected with through Ancestry.com shared Lloyd’s prison record and letters that he exchanged with the Slaback family while incarcerated. He had committed some petty crimes as a child, but those records were expunged. The newspaper clipping describes what may or may not have been his first crime as an adult. It appears to have been the first time he was sentenced to prison.

There were two major factors in the 1920s and 1930s that led to moral panic over gangs

and criminal activity:

- the Great Migration (1915–1940) of Blacks into northern cities, and

- the subversion of Prohibition laws, most infamously by Al Capone.

In sundown towns

like La Crosse, the police focused their efforts on lower- and working-class Whites. There was little tolerance for young people who were unwilling (or unable) to work. Lloyd died long before I was born, so I have no idea what he was like in real life. In this book, I painted him as funny, handsome, and artistic, but also reckless. He might have struggled in any period, but I wonder what he might have accomplished with more tolerance and support. In letters from prison near the end of his life, he expressed regret over his poor choices.

The 1930 Census is the first one where Lila Slaback appears in the record. She was eight years old, and her family was living in the house on Kane Street in La Crosse. Like the 1920 Census, enumerators were asked to record information about literacy, education, and employment. The question of whether the family owned a radio was new; the Slaback family did own one. Lila’s father, John, was recorded as working odd jobs

for hourly wages (not a salary).

For more information, see Deidre Bair1, James Noble Gregory2, James C. Howell3, and James W. Loewen4.

Al Capone: His Life, Legacy, and Legend (New York: Doubleday, 2016).↩︎

The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).↩︎

The History of Street Gangs in the United States: Their Origins and Transformations (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2015).↩︎

Sundown Town: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism (New York: New Press, 2018).↩︎