Chapter Nine

In 1930 there were still eight people living in the house that Lila’s father had built on Kane Street, but it seemed unbearably quiet without Theron and Izro. To cheer the family up, her father decided to buy a radio. They made a place for it near the table so there would be plenty of room to sit and listen. Lila’s mother insisted that dinner time should be for conversation, but otherwise their evenings were suddenly filled with music, news reports, and serial programs. A quick favorite for the whole family was Amos

which was about two friends trying to make it in the big city. The show was funny, but it also made them feel better about their problems—at least the Slabacks weren’t that stupid. While most of the programs on the radio were entertaining, the news reporters were always very serious talking about the stock market, unemployment, and President Hoover. Her father was not working as much as he did the year before, but Lila thought her family was doing fine. They had a house to live in and clothes to wear, and the shelves in their basement were loaded with jars of food.n

Andy,

Theron built two wooden benches in the back of the truck so the whole family could ride. During the summer, they started taking trips out into the country. Although it was nice to spend time with their uncles, aunts, and cousins (so many cousins that Lila could not keep track of all their names), they could also do some work in exchange for food. A few hours of weeding and picking might lead to crates of string beans, baskets full of zucchini and tomatoes, or bushels of apples. Some of it they ate right away, but Lila and Veda would help their mother preserve the rest so they would have plenty of food for the winter. It was hot work since the jars had to be sterilized and the vegetables needed to be blanched in boiling water. Lila did not enjoy eating spinach, but she loved watching it shrink in the heat—a whole basket of spinach could fit into a single jar after the blanching process. When meat was available, they turned it into sausages. The basement was cold, but salt and spices would keep the meat from going bad regardless of the temperature. One year—inspired by a neighbor from Germany—Lila’s mother decided to try making sauerkraut. Good lord! Lila thought the smell was awful, like rotting eggs and sweaty socks. No matter how hard she tried, Lila could not force herself to eat it, although her father claimed that it was delicious with the sausage. They never made it again.

One day, Uncle Frank and Aunt Hattie came to visit, and they decided to take a walk out by the river. Veda and Lila were nervous and held hands the entire time, but it was beautiful that day. The sky was stunningly blue, and the banks were lush with milkweed, black-eyed Susans, and Queen Anne’s lace. As they walked along the coarse sand and rocks that had been worn smooth by the river, Uncle Frank told a story about Lloyd. Lila never forgot it because it was quite revealing about their family.

One day, when Lloyd was eleven years old, he went to a birthday party. (What was the name of that friend?

he asked Aunt Hattie, who shrugged and said she couldn’t remember.) The party was held on a steamboat, which was docked just two blocks away from their house on State Street. Since it was hot in August, the party was held in the evening—they were planning to take a moonlight cruise

on the river. One of his friends knocked on the door and they walked down to the river together. Uncle Frank and Aunt Hattie had to go to work the next day, so they were going to bed at their usual time. They told Lloyd that they would leave the door unlocked: Have a good time, be careful, and please be quiet when you get home.

Lloyd promised that he would, so everything seemed fine. When Aunt Hattie checked his bed in the morning, however, Lloyd was not there. She woke up everyone in the house. Frank…Lloyd is missing! Kenneth…have you seen your brother?!

She made everyone go outside to start knocking on doors. After what seemed like forever (but was probably just a few minutes), one of the neighbors told Aunt Hattie that her son had been at the same party and invited Hattie to take a seat and wait for him. When William (Oh right, that was his name

) arrived in the sitting room, he said, The last time I saw Lloyd, he had fallen asleep on one of the benches.

Although Aunt Hattie had been running through all the worst-case scenarios in her mind (maybe he drowned, maybe he was hit by a car!), she realized now what had happened: Lloyd was a sound sleeper, and he didn’t wake up when the party was over. She thanked William and rushed back home to call the steamboat company. They told her that the name of the ship was The Capitol, currently on its way to Winona (on the Minnesota side of the river). She thanked them and rushed out to send a telegram to the Winona police: Lloyd Slaback, age 11, fell asleep on The Capitol. Please send him back to La Crosse.

Knowing that it would take hours—maybe even a day—for Lloyd to return, Aunt Hattie and Uncle Frank went off to work. He was home by the time they returned, eating a sandwich and playing card games with Opal and Kenneth like nothing had happened. The next day the story was in the newspaper: La Crosse Boy Sleeps on Boat, Lands at Winona.

Lila’s mother said, My goodness, that must have scared you half to death!

Uncle Frank said, Not really…all’s well that ends well.

Aunt Hattie blushed. I was horrified. Why did the reporters have to write that story? The neighbors could not stop talking about it; they said I was a bad mother for not waiting up. That incident was the reason we left State Street and moved to the house on Copeland Avenue.

For a few moments they walked in silence, and then Hazel changed the topic to preparations for dinner.

Was Aunt Hattie really a bad mother? Lila and Veda exchanged nervous glances and Veda gave Lila’s hand a little squeeze. Her family wouldn’t forget about her and let her fall asleep on a steamboat…would they?

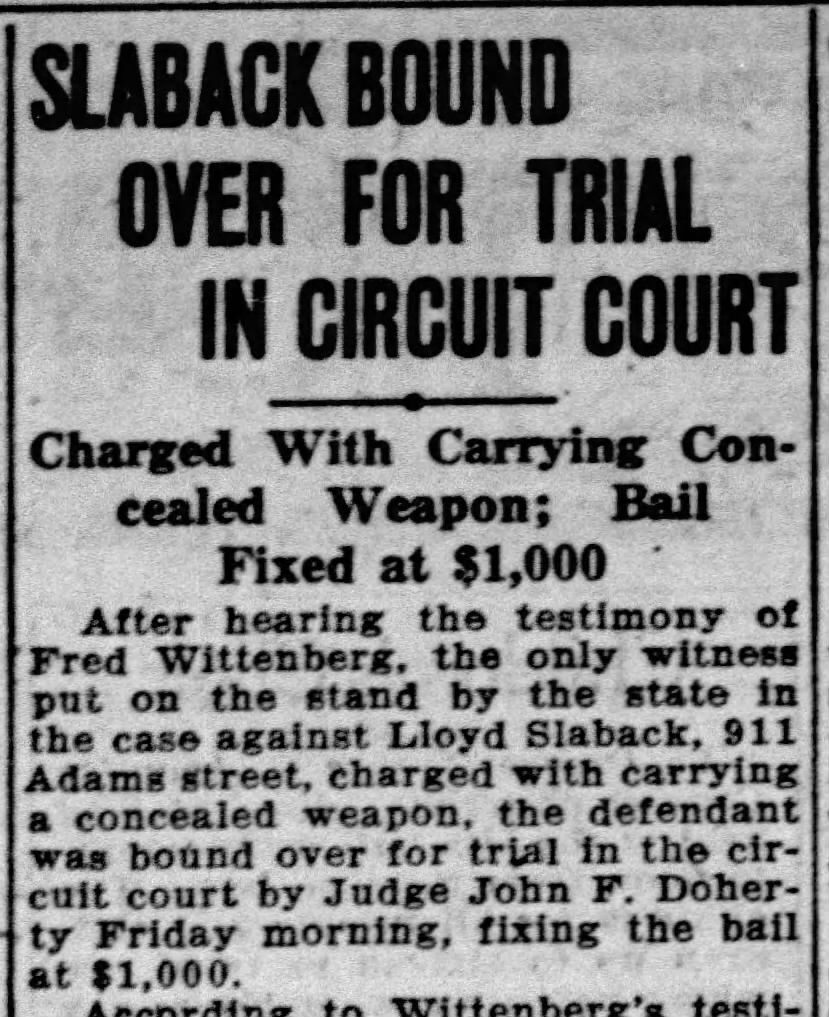

Lloyd was in the newspaper again that year. Well, I never…

said Lila’s mother. They were all sitting at the table and Lila’s father had just finished reading the article out loud. Lloyd had threatened someone with a loaded gun. He told the judge that he was too drunk to remember what happened.

$1,000 was an unimaginable amount of money. Lloyd was going to prison for sure. Her father said, Lloyd is no longer welcome in this house. I want all of you to stay away from him. Do you understand? Please tell me that you do.

Around the table there was a chorus of Yes, Father.

Lyle’s head was hanging down; he considered Lloyd a friend. When Lloyd worked for their father, his jokes made the time go faster. Lloyd was as funny as anyone on the radio.

John put his hand on Lyle’s shoulder. Lyle, I also want you to promise; Lloyd is drinking in public and spending time with the wrong kind of people. He is nothing but a hoodlum.

Lyle said, I understand…I promise.

Lila knew that going to prison was bad, but she was confused about why the family was pushing him away. Did they have to punish him too?

Notes

Radio became a form of entertainment in the 1920s with the start of broadcasting. Compared to films and theater productions, listening to the radio was free (after the radio had been acquired) and did not require travel or time outside the home. Radio programs could also be enjoyed by the entire family simultaneously. Ownership expanded rapidly in the 1920s and 1930s, even in working-class households. Amos

was an audio version of a minstrel show, featuring two White voice actors who wildly exaggerated Black lifestyles and speech patterns. The radio also delivered the news to listeners who could not access newspapers.n

Andy

Unlike many families in the Great Depression, the Slabacks were not forced to move or split up. Their connections with family members who were still farming (and their ability to preserve food by canning) may have saved them. Both of my grandmothers knew how to can food as a life skill and not as a hobby. My mother loved canned sauerkraut, but I always hated the smell. When I was small, she canned peaches and strawberry preserves for us to enjoy during the winter.

The winters are very long in Wisconsin. It can start snowing as early as September and end as late as May. The long, cold, dark months are depressing if you don’t find new entertainment. Some people enjoy winter sports like skiing, sledding, ice skating, and ice fishing. My father’s family was more interested in storytelling. The story of how Lloyd fell asleep on a steamboat is exactly the kind of story they would have told over and over—for fun, but also as a cautionary tale. Be careful. Don’t lose track of your friends. Don’t scare your parents half to death.

For more information, see Ethan Blue1, Tim Brooks2, Russell Freedman3, and Michele Hilmes4.

Doing Time in the Depression: Everyday Life in Texas and California Prisons (New York University Press, 2012).↩︎

The Blackface Minstrel Show in Mass Media: 20th Century Performances on Radio, Records, Film and Television (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019).↩︎

Children of the Great Depression (New York: Clarion Books, 2005).↩︎

Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922–1952 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997).↩︎