Chapter Seventeen

Hazel seemed to have given up on life. During the day, she stayed in her bedroom and slept. At night, she listened to the radio and drank whiskey. Lyle was the one who bought it for her. Nobody talked about Hazel’s drinking problem, but Lila knew; she had never been a good sleeper and often saw her sitting alone late at night. On the rare occasions when Hazel ventured outside, the neighbors would always say, Why hello, Mrs. Slaback, I haven’t seen you in ages! Good to see you up and about,

but Lila was sure they could see that something was very wrong. Hazel was gaunt and her hair had turned completely gray.

Aunt Hattie was the one who decided that something must be done. Lila was wary about her schemes, but on this she had to agree: her mother’s behavior was not normal. The cure, Aunt Hattie said, was to get Hazel back into the community; being of service to others would help her stop focusing so much on her own situation. When presented with the idea, Hazel said, Fine, but no churches; I will never stop being angry at God for taking my son away.

Lila’s heart skipped a beat; it was the first time her mother had said anything about the cause of her turmoil. Without batting an eye, Aunt Hattie said that would be no problem; the American Legion Auxiliary and Wilson Colwell Relief Corps were always looking for new members.

Much to Lila’s surprise, within a few months her mother was an officer for three different organizations. Hazel’s specialty was running bunco

games for charity. Everyone knew that bunco was a dice game of pure luck—associated with speakeasies and criminals—but it gave Hazel a dark sense of glamour. It also raised a lot of money. Hazel started joining the family for meals and regained the weight she had lost, but she never stopped drinking entirely. Later in life, she took up rug braiding as a hobby, keeping a stash of whiskey in her box of fabric strips.

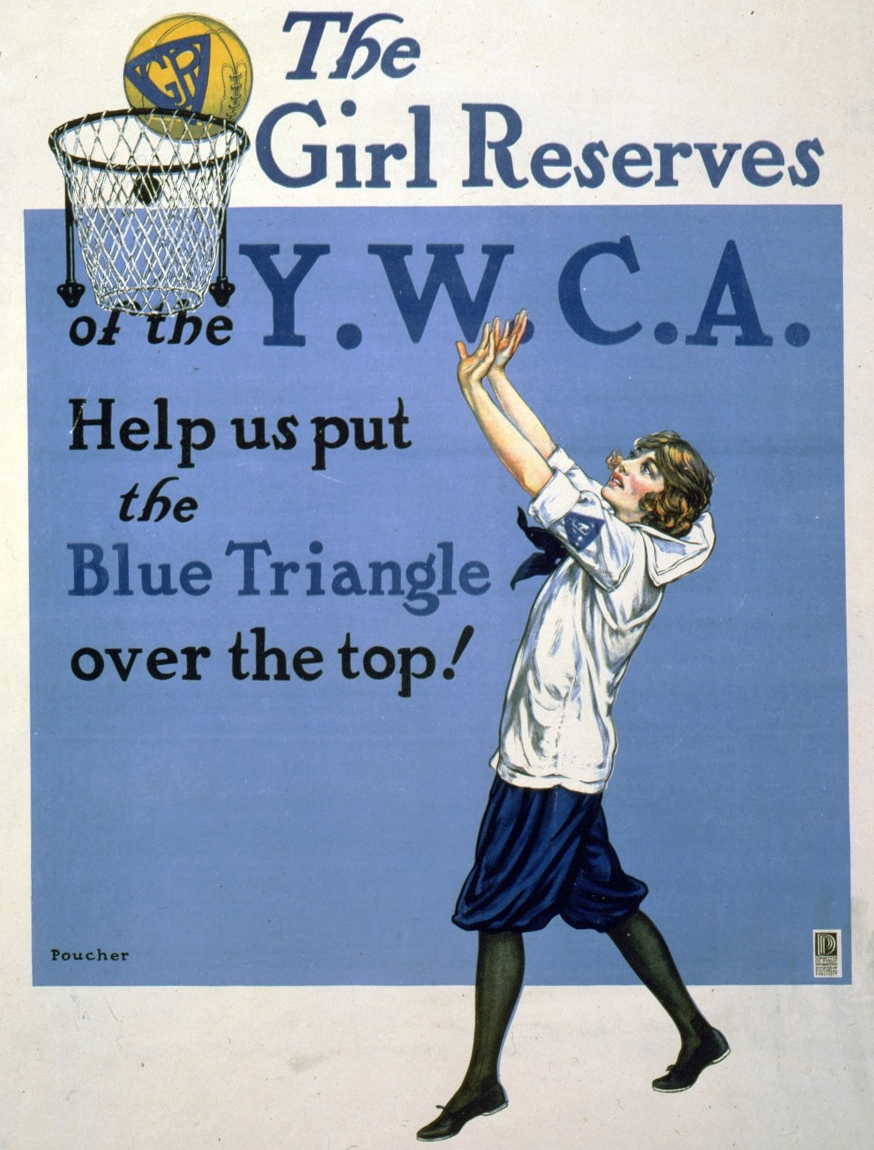

Lila joined the Girl Reserves. Ironically, Aunt Hattie had switched from being concerned that Lila would never get invited to parties to being worried that she was a fast

girl who would bring shame to the family. Her daughter, Opal, had been in the Girl Reserves, and she thought it was outstanding for building good character.

Lila knew the group required uniforms and was worried about the cost, but Aunt Hattie assured her that she would pay for it. Lila was excited for an opportunity to get out of the house and to do something on her own. Aunt Hattie still had her daughter’s old uniform; unfortunately, it was too small for Lila to wear. Lila was relieved when she hired a dressmaker to make a new one instead of taking her shopping. The outfit had a white shirt, blue culottes (which felt odd, since Lila had never worn pants for anything besides chores), and a blue kerchief. It made Lila feel like she was posing for a box of Cracker Jacks. During the fitting, the dressmaker asked her why she kept giggling. Lila stopped and made up a lie to avoid seeming rude, Oh…I was just thinking about something I heard at school today.

The dressmaker’s daughter had also been in the Girl Reserves; she told Lila how proud she was of her daughter, who was all grown up and married with children of her own.

At the first meeting, Lila received a small poster with the group’s pledge that she could hang in her bedroom. She had to admire how the first letter of each line spelled out the name of the organization. It would make the pledge easier to memorize.

As a Girl Reserve, I will try to beGracious in manner

Impartial in judgment

Ready for service

Loyal to friendsReaching toward the best

Earnest in purpose

Seeing the beautiful

Eager for knowledge

Reverent to God

Victorious over self

Ever dependable

Sincere at all times

She was skeptical about her ability to live up to it. Maybe Veda could do it,

she thought to herself. Veda never complained about the chores. She was beautiful, hard-working, loyal to her friends, practically perfect in every way. Lila admired and loved her, but at times she wanted to hammer a nail into her perfect forehead.

Nothing she did would ever be as good as Veda. Veda was a good girl.

Earl had also been a good boy.

He could never be bad, since being dead prevented him from doing anything wrong. Lila reflected that the rest of them took turns being the bad one.

Theron had killed Earl. Lyle killed that pedestrian. Cecil had a shotgun wedding. All of those things were pretty bad. Lila had never done anything like that, but she was not a young lady like Veda. She ate too much, laughed too much, and asked too many questions. She hated doing the chores and had to be reminded sometimes to do them. She wasn’t a good student or as popular as Veda. She wasn’t sure it was possible (or even desirable) to be one of the good ones.

Notes

Life has taught me that when times are tough, people notice. They might not say anything, but they see what is happening. Our bodies reflect our inner turmoil.

My mother told me that her grandmother (Hazel) always kept a bottle of whiskey in her box of supplies for making braided rugs. Multiple people have told me that she was not an easy person to get along with. In an earlier version of this book, I described Hazel’s life as a child and young woman, trying to make sense of how she turned into a bitter adult with a drinking habit.

In the late 1930s, Hazel Slaback suddenly began to appear in the newspapers; this was normal for Aunt Hattie and Borgny (Theron’s wife), but not for her. I suspect that Aunt Hattie nudged her to get involved in charity work, but it was always for secular organizations. Lila was listed in the newspaper as a member (and once as an officer) for the Girl Reserves, an organization for white, adolescent girls to develop good character,

similar to the YWCA or Camp Fire Girls. In this chapter, we get insight that Lila knows what her family and society expect her to do, but she is not sure that she is capable of doing it (or even wants to). This is a hint that her life might take a more scandalous turn.

In the 1930s and 1940s, ready-to-wear was not as common for women as it was for men. It would not have been unusual to hire a dressmaker or to make an outfit at home.

For more information, see Jennifer Helgren1, Jenna Weissman Joselit2, and Nina Mjagkij and Margaret Spratt, eds.3

The Camp Fire Girls: Gender, Race, and American Girlhood, 1910–1980 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022).↩︎

A Perfect Fit: Clothes, Character, and the Promise of America (New York: Henry Holt; Company, 2014).↩︎

Men and Women Adrift: The YMCA and the YWCA in the City (New York University Press, 1997).↩︎